It was the strange, offbeat answer heard ‘round the world. When confronted about her relationship with Wall Street donors during Saturday night’s Democratic debate, Clinton launched into one of the more bizarre responses of the night:

You know, not only do I have hundreds of thousands of donors, most of them small, I am very proud that for the first time a majority of my donors are women, 60 percent. (APPLAUSE) So I—I represented New York. And I represented New York on 9/11 when we were attacked.

Where were we attacked? We were attacked in downtown Manhattan where Wall Street is. I did spend a whole lot of time and effort helping them rebuild. That was good for New York. It was good for the economy. And it was a way to rebuke the terrorists who had attacked our country. (APPLAUSE)

As CBS’s transcript shows, Clinton’s response wasn’t immediately received as absurd. The crowd, which had been sedate for most of the evening, applauded loudly twice as her remarks unfolded. But then things took a turn.

Online, Twitter exploded with bewildered commentary. Had Clinton really just explained away the millions of dollars she has accepted from Wall Street over the years by bringing up 9/11? Did she really append the gender of her donors to that Escher painting of an answer?

The gender card and the 9/11 card in one answer. This woman is a pro.

— Molly Ball (@mollyesque) November 15, 2015A little later in the debate, moderators presented Clinton with the following tweet from law professor Andy Grewal, probing her earlier response.

Have never seen a candidate invoke 9/11 to justify millions of Wall Street donations. Until now. @HillaryClinton #DemDebate

— Andy Grewal (@AndyGrewal) November 15, 2015In her reply, Clinton laughed nervously, doing little to exonerate herself. “I’m sorry that whoever tweeted that had that impression,” she said, “because I worked closely with New Yorkers after 9/11 for my entire first term to rebuild. And so yes, I did know people. I had a lot of folks give me donations from all kinds of backgrounds, say, ‘I don’t agree with you on everything. But I like what you do. I like how you stand up. I’m going to support you.’ [LAUGH] And I think that is absolutely perfect.” By dismissing Grewal’s interpretation and then doubling down on her original statements, Clinton missed an opportunity to build her answer into something coherent—and pundits noticed.

As critical assessments poured in over the weekend, the Clinton campaign attempted to pin the issue on Grewal. “It was the person on Twitter who connected [9/11] to donations. That is not what she did,” Clinton communications director Jennifer Palmieri said after the debate. John Podesta, the campaign’s chairman, later told Yahoo News, “I think that she was feeling that unfair charges were made and she pushed back,” avoiding a discussion about the substance of Clinton’s remarks.

And it was precisely the substance of those claims that quickly unraveled over the weekend. While Clinton praised her “small donors”, large donations make up 81 percent of her campaign contributions. The disagreements Clinton had hinted at between herself and Wall Street seem rather meager when examining her record. As for New York firms donating to her because of residual respect over her handling of 9/11, it turns out Clinton was a top recipient of Wall Street cash long before the terror attacks of 2001. Further, confidence in her post-crisis governing abilities wouldn’t explain the $125 million she and her husband Bill have accepted in personal payment from major firms since 2001, mostly in return for speaking engagements. Nor would it explain why, more than a decade down the line, Hillary Clinton is still making $200,000 per speech at banks like Goldman Sachs.

Clinton and her campaign, which is composed of some of the savviest, most experienced political strategists around, surely knew none of this would hold water. Yet it’s also almost certain, given her team’s experience, that this was a pre-fabricated answer to an issue one would expect to arise in a confrontation with Senator Bernie Sanders, who has made refusing big money donations a cornerstone of his campaign. Which raises the question: Why would such a smart, skilled politician deliver such a clumsy, frangible answer, especially the sort that would open her up to the PR nightmare of appearing to exploit 9/11 immediately after the heinous Friday night attacks on Paris?

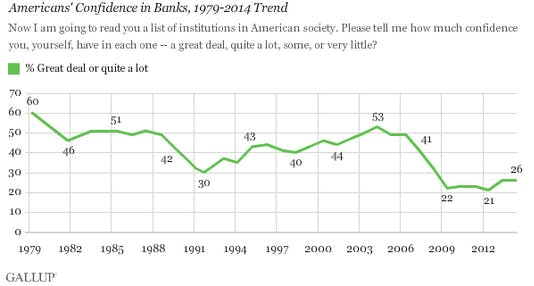

The answer, it seems, is that there was just nothing else to say. Consider the alternatives. Clinton could have just copped to it, with a cordial-sounding response along the lines of, “Yes, I’m friendly with some Wall Street firms, and with plenty of other important American industries.” Unfortunately, confidence in banks is near record lows, and roughly two-thirds of Americans say they’re still angry about the role of big banks specifically in the economic crisis that began in 2008. Dedicated poll-watchers, the Clinton camp probably realized honesty would not be, in this case, the best policy.

Clinton could’ve said that, with finance being a major industry in the state of New York, she was obliged by her post as senator to protect its interests, and received a great deal of support in return. This would perhaps exonerate her personally, but it wouldn’t get her out of the quagmire Sanders is in for saying virtually the same thing about his record on guns, which stems from his representation of the rural state of Vermont. Further, this sort of answer would’ve conceded that there was something of a quid-pro-quo relationship between Clinton and the firms who support her, something she seems at pains to deny.

Clinton could’ve said that, in a political climate as awash with big money as ours, refusing to take donations wherever they come from is tantamount to surrendering to Republicans. The trouble is that assertion wouldn’t have stacked up well against Sanders’s argument that what “we need to do is show by example that we are prepared to not rely on large corporations and Wall Street for campaign contributions.” Sanders himself has notoriously refused such contributions, and yet his campaign funding hasn’t lagged Clinton’s by all that much. And an admission like this would’ve all but confirmed Sanders’s point about the corruption of politics by overwhelming financial interests.

Clinton, lastly, could’ve said that, as a politician, she has little time to engage in the labor market to make money to support herself and her family, and that short but well-paid speeches were an unfortunate necessity. Most people, of course, don’t require $125 million over 15 years, and such a claim would likely have revived memories of her remark that she was “dead broke” upon leaving the White House, which revealed that “dead broke” doesn’t appear to mean the same thing to the Clinton family that it means to most.

In other words, Clinton, smoothest of the smooth, was stuck. While her bungled response will likely be forgotten as this debate recedes in memory and others take its place, what it wound up proving is that even the most skilled politicians have a hard time rebutting the claim that big money totally dominates politics.