There is a significant difference between what you want to eat when you’re high and what you want to eat in order to get high. This is the conflict of the weed cookbook, a genre that aims to hook both stoners and home cooks alike by treating the friendly herb as more than just a psychoactive drug. And while the vape contingent might argue that theirs is a more efficient way to ingest weed without the health risks of smoking, the marriage of the home cooking movement and weed culture is inevitable, and full of possibility.

Herb: Mastering the Art of Cooking with Cannabis is an ambitious attempt to bring

together the weed brownie set and the dinner party set, medical mary jane

proponents and recreational smokers, the anxious and the epicurious—all through

the magic of cannabis-infused oils and butters. The book was successfully

crowdfunded last year and published this fall by the people at The

Stoner’s Cookbook, a

recipe hub for the cannabis inclined. This is the team’s second cookbook (the

first was an e-book filled with more basic recipes) and with it, they hope to

educate readers on this “beneficial herb with pleasant effects,” and to inspire

them to bring it joyfully into their home kitchens.

I’ve eaten edibles

before—there was a shortsighted and traumatic brownie-meets-Megabus experience

in 2012, and a handful of cheerier times since then—but I never made them at

home, because I heard that making cannabis-infused oil stinks up your whole

house and because I’m lazy. I’ve certainly never gone the savory route. This is

perhaps a common experience: Edibles sound like a good idea, until you factor in

logistics (and legality). But Matt Gray, CEO of The Stoner’s Cookbook, has high

aspirations for the practice. As he told me over the phone, the authors wanted

the book to be classy, to “elevate” cannabis’s culinary reputation. Gray wants

it to be accessible enough to grace the front table at your local Barnes &

Noble. As we signed off, he mentioned something about “how this book can help

millions of people around the world.” Gray’s comment may sound like the sort of

stoned idealism that precedes a greying deadhead’s muttering “peace and love,

man,” but also: Who’s to say he’s wrong? Who’s to say that edibles won’t

eliminate pain and lead to peace? Who’s to say that a brownie can’t solve our

problems, or at least a small slice of them?

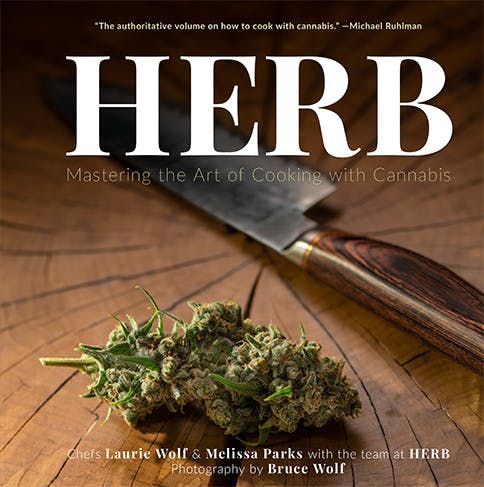

Looking at Herb, you can certainly imagine it on display at an independent Colorado bookstore, if not Barnes & Noble. Its cover checks off all the boxes of an on-trend, coffee table-ready cookbook: The letters are large, dramatic, and few; the lighting is also dramatic, highlighting a seemingly hand-hewn chef’s knife and a scarily large nug of “cannabis” (the authors’ preferred term for what the rest of us know simply as “weed”). The subtitle—“Mastering the art of cooking with cannabis,” hovering in grey just above the knife—references Julia Child’s seminal cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, the American ur-text of French cuisine. Child was our first home cooking celebrity, and her recipes and instruction in French Cooking have become general household knowledge; she changed the way our country cooks. For their own attempt at timelessness, The Stoner’s Cookbook team enlisted two experienced and 420-friendly chefs—Portland’s Laurie Wolf, who owns the artisan medical edibles company Laurie & MaryJane, and Colorado’s Melissa Parks, a graduate of Le Cordon Bleu in Minneapolis and former head chef at edibles company Bakked—to develop recipes, and brought on seasoned cookbook writer Michael Ruhlman to fine-tune the cannabis extraction instructions and act as a consultant. Herb aims to be the French Cooking of weed, the beginning of a new moment in American food culture. After my first flip-through I was underwhelmed but still excited, ready to eat some drugs.

I resolved to make two recipes: one savory, one sweet. I began with a baked (get it?) pasta with artichoke pesto, which sounded comforting and exciting and like something I’d want to eat if I were high. The pesto itself felt new: Herb’s recipe has you blitz canned artichokes with parsley, garlic, lemon, and nuts, then add in a long pour of olive oil and a few teaspoons of cannabis-infused olive oil—“canna-olive oil.” It’s a nice way to make canned artichokes taste fresh and bright, and it’s also a handy alternative to traditional pesto; I’ll use it again (sans weed). You toss it with cooked pasta, top the result with a breadcrumb-herb mixture and wait for it to bake.

Even so, until I pulled the pasta out of the oven, I was a little annoyed by the idea of weed cookery. To make canna-olive oil, you must first “decarboxylate” your cannabis by breaking it into bits and toasting it in a low oven for 40 minutes; this converts THCA into THC, the thing that gets you high, and develops its flavor, just as toasting spices does. Then you grind it and cook it with olive oil on the lowest heat you can find for three hours. Cannabutter takes five hours of low cooking, then an overnight rest. Not to mention that each oil recipe calls for an ounce of weed, which might run you $300, making the ingredient more expensive than caviar. This is too much for me. I am not that dedicated to edibles; I enjoy smoking, and it only takes me a few seconds to do. After I held my pan of fully-baked pasta, though, my first reaction was a squeal, and then a shriek: “I CAN’T BELIEVE THERE’S WEED IN THIS!”

The pasta came out bright and lemony, with a crunch that crumbled and plenty of green. I wished there had been more oil in the pesto, and that there had been oil in the crumb topping, and that the recipe had told me to cook the pasta to al dente, or just-underdone, which you usually want to do in baked pasta recipes since the noodles continue to cook in the oven. (These are the sorts of small omissions that make Herb annoying to a persnickety cookbook reader like myself, and unhelpful to a novice cook who risks ending up with mushy pasta.)

After an hour or so I felt that fuzzy balloon-like feeling in my arms and then in my chest, the high moving towards my head rather than ringing from it as it does when I light up the ol’ pipe. Everything was funny, sure, but my emotions were also deeper and sharper: delight more piercing, sadness more swift. Later on in my recipe testing I would cry with more urgency than I had in weeks, but it passed painlessly, like a sun shower.

A few days later I went for the very-straightforward granola: nuts, seeds, oats, some oil, some sugar, cinnamon. I was deeply offended by the fact that the recipe didn’t call for salt, which I think that all granola recipes should do: Even if you’re not riding the “salty sweets are good!” bandwagon, a little bit of salt enhances other flavors, which why it’s in your not-salty cookies and cakes. It was good granola, fine, extremely basic. It’s the perfect thing to have (well-labeled!) in your cupboard if you’re looking for a tiny high. In making it I felt the tension between the authors’ desires to provide simple, no-frills recipes, like granola and guacamole, and their more global or highbrow aspirations: a chicken báhn mì, dumplings with asian dipping sauce, seared sirloin with savory bread pudding, a bone-in tomahawk ribeye served with garlic-herb cannabutter.

My frustration with Herb—which contains a number of appealing recipes I’m interested to try, and straightforward instructions on how to make cannabis-infused oils—is its murky positioning somewhere between “basics” and “cuisine.” A wholly basic cookbook it is not: its brownie recipe includes two different sauces; its chocolate chip cookies call for dried apricots. You can’t call it cuisine, or even current, either: Herb contains some very-90s recipes like Asian Chicken Salad and shortcuts like using store-bought pizza crust for a soppresatta and green onion pizza that would otherwise sound like something you’d find on a Brooklyn menu. I know that my cookbook expectations may be higher than those of the average consumer because I am a brat and also a food writer, but I also know we can do better to teach and entertain our readers, even if all they want to do is get high off a bowl of pasta.

After the extraction instructions, at no point did I feel like I was learning new techniques or understanding ingredients in a new way. I wanted a thorough introduction to cooking with weed that didn’t read like a chipper pamphlet at a liberal doctor’s office; I wanted building blocks and templates that could empower me to read one recipe and come up with another. How are you supposed to get high off of your grandma’s pasta if the basics of adapting it aren’t thoroughly explained?

The feat of appealing to beginners and seasoned home cooks alike is a tricky one: It requires a strong voice and confident, thorough instruction. It requires personality and institutional knowledge. And it requires thoughtful, exciting headnotes, the chunk of a few sentences or paragraphs that introduce recipes and offer relevant information not covered in the instructions that follow. These give a cookbook author the opportunity to do an array of things: to tell their story, to shed light on ingredients and technique, to walk the reader through a guided meditation where they envision this recipe in their life, on their tables, in their mouths. In this, Herb has, for the most part, failed. Its authors tell us that green juice is all the rage right now, and that you can customize your own granola. But this is a cookbook, not a clipped recipe from a newsstand magazine with a 50-word limit on their headnotes. I want stories that inspire me to move from my couch to my stove! I want tasteful and self-aware jokes! I want a new genre of weed writing that doesn’t exist yet! I want voice, and I want perspective. In Herb, the former is weak, and the latter is less culinary and more a wish that all people the world over use cannabis to solve their problems.

Worse, the photos are jarring, usually too close-up with distracting patterned backgrounds and overly saturated color and uninspired food styling. Food photography has reached its apex, and a cookbook without perfect photos (or gorgeous, intentionally imperfect photos) feels like a misstep. Which is why, when Herb reaches for cheffy and elegant, it feels out of touch. And when it attempts something simpler, like guacamole, the book comes off as unimaginative and redundant.

The market for traditional cookbooks is saturated: We have cake pop cookbooks, toast cookbooks, green juice cookbooks, countless blogs-turned-cookbooks, and conceptual cookbooks that weigh more than infants. But we have yet to see a Joy of Cooking (With Weed!); Mark Bittman’s move to California has not yet brought about a How to Canna-Cook Everything. Though Herb has elevated weed cooking slightly past the stale stoner brownies of yore, it’s no Julia Child. And while its publication represents an exciting shift towards ambitious and mainstream weed cookbooks, I doubt this is the one that will remain on our shelves in five years, or the one that will earn the respect and devotion of cookbook enthusiasts.