“Never was so much journalistic talent focused for so long on an event that in the last analysis boils down to two people uttering the words ‘I do.’” So wrote Hollywood columnist Dorothy Kilgallen in the spring of 1956, reflecting on a recent assignment to cover the wedding of Prince Rainier and Grace Kelly. Nearly 2,000 journalists had gathered in the tiny principality of Monaco, at the time the largest collection of media personnel ever assembled in one place. NBC had six correspondents on the ground to cover D-Day; it sent nine to report on the so-called “The Wedding of the Century.”

The global media attention couldn’t have come at a better time for Monaco, which was mired in a period of financial decline. Despite remaining profitable for much of the Second World War, the Monte Carlo casino had ended the 1940s with one of the worst years in its history, showing a 75 percent operating loss and a 90 percent decrease in the number of visitors compared to prewar figures.

Many tourists had lost their taste for the very sort of European elitism that Monaco’s boosters had been trading on since Monte Carlo’s founding as the world’s first modern casino-resort, roughly a century earlier. Tom Wolfe, in a 1965 essay about the postwar rise of Las Vegas, suggested that the original had lost ground to its American imitator because it still carried too much “upper-class baggage.” As the novelist David Dodge put it, postwar Monaco “had lost its chic. Glamourville was strictly for squares.” Its legacy was now a liability. In 1952, Dodge had written a thriller based in the French Riviera, To Catch a Thief. Little then did he know that the star of its eventual film adaptation, Grace Kelly, would soon provide the key to revitalizing Glamourville.

Prince Rainier ascended to Monaco’s throne in 1949 just shy of his twenty-sixth birthday. Soon after taking control he’d tried unsuccessfully to convince American hoteliers to build in the principality. Rainier also failed in an attempt to arrange for two American investors to buy a majority share in the casino; the scheme was quashed by admonishing words from French officials, worried about Americans wielding too strong a financial influence in the principality.

Rainier was meanwhile engaged in a power struggle with the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, who between 1952 and 1953 reportedly bought 200,000 shares in the casino through various proxy buyers, a majority share. Onassis who’d headquarted his shipping empire in Monaco, had a vested interest in helping maintain its tax-free status. Monaco’s sovereignty, as Onassis knew, depended not only on its solvency but on the continuation of the Grimaldi line.

In 1955 Onassis moved to resolve the issue of an heir while also bringing some much-needed media attention to Monaco. He suggested to Rainier’s chief advisor that an American film star might make an ideal bride for Rainier. The prince was receptive to the idea; just as centuries of royal houses had married into other dynasties to consolidate their power, so too could the Grimaldi dynasty by marrying into Hollywood “royalty” align itself with another powerful house—the studio system. It was important that the bride be American, rather than European so that Monaco would be linked to the same global client base that consumed American movies. Rainier’s tiny principality would in turn be associated with the most powerful and modern nation in the world.

The public responsibilities of the future Princess of Monaco wouldn’t have been expected to be much different than those of a postwar film celebrity. Hollywood stars, with legions of followers, were often portrayed as “royalty” (John Wayne, as the “Duke,” for example), while actual monarchs, who are in most cases well-trained public performers, might also be considered highly accomplished actors.

Biographers have claimed that Kelly wasn’t the first choice for the role of Princess of Monaco. Onassis had allegedly suggested Marilyn Monroe as a potential mate (she was game, though at first she thought Monaco was in Africa). Whether or not this story holds any truth, Rainier and his entourage apparently felt Monroe lacked a sufficiently dignified public image.

By contrast, Grace Kelly projected refinement and poise in person, onscreen, and in other media. She refused to include her measurements in press kits or overly expose herself on film. In her eleven films she played a wife or fiancée in more than half, and in the remainder (save for Rear Window) she was chaperoned by a doting relative. “With Grace,” an unnamed MGM publicist told the Chicago Tribune in 1957, “we put on a high style, a high line campaign.”

Alfred Hitchcock said that he was attracted to Kelly’s “sexual elegance” when casting To Catch a Thief; as she embodied his stated preference for casting women whom he believed exuded a reserved but secretly smoldering sexuality. In an interview with Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock explained how he “deliberately photographed Grace Kelly ice-cold [and] kept cutting to her profile, looking classical, beautiful, and very distant.” For Hitchcock the most interesting women, sexually, were English and other northern Europeans; their exterior reserve made them much more exciting than the (in his opinion) more overtly sexual Italian or French women. “Sex should not be advertised,” he said.

The year Kelly met Rainier, she played a princess who marries for position rather than love, aided by a matchmaking friar, in Charles Vidor’s The Swan. (MGM would hold the film’s release until April 1956, to coincide with her wedding.) By contrast, when Marilyn Monroe rubbed shoulders with fictional royalty onscreen, as she did in her 1957 film with Laurence Olivier, The Prince and the Showgirl, she wasn’t granted such equal footing.

The first meeting between Kelly and Rainier was itself a staged media event. The director of Paris Match, Pierre Gallante, suggested to Kelly, who was returning to the Riviera in the spring of 1955 at the invitation of the organizers of the Cannes Film Festival, that a meeting between her and the Prince would be a great photo opportunity.

Rainier offered Kelly a tour of the palace grounds, with the highlight being his menagerie of exotic animals. It was by all accounts an awkward first date. Afterward, Rainier’s confessor, a Father Tucker, who, like Kelly, was an Irish Catholic with roots in Philadelphia, worked as matchmaker. He wrote the actress, thanking her “for showing the Prince what an American Catholic girl can be, and for the deep impression this has left on him.”

The ensuing courtship, such as it was, was brief. Rainier’s advisors had planned for the Minister of State to announce the engagement from the Grimaldi Palace in early January 1956, while issuing an American press release that would include a stock image of the couple. The Kelly family anticipated that American reporters wouldn’t stand for such a paltry offering, and after some firm words from Grace’s father to the Prince, brokered a compromise. The Minister of State did announce the engagement on the morning of January 6, 1956, but on the same day—though several hours later, due to the time difference—the Kelly family was allowed to hold a morning press conference in their Philadelphia home.

Kelly remained poised throughout the raucous conference, attended by over 100 journalists, but her future husband was visibly upset, as reporters asked the couple how many children they would have, while photographers stood on the family piano to get a better shooting angle. At one point Rainier reportedly muttered: “It’s not as if I belong to MGM.”

During the months between the engagement announcement in January 1956 and the ceremony in April, Rainier and his handlers often worked at cross-purposes with the Hollywood press that had been so vital in shaping the same public image they now hoped to associate with Monaco. The competing camps were like two authors battling over how their protagonist should act. As the couple met with the press at various intervals in early 1956 there was confusion about which side was more in need of the services of the other.

By choosing to marry a European monarch, Kelly seemed to reject the kinds of American dreams of upward mobility that she helped to fuel as a film celebrity. It seemed that regardless of how successful an American man who worked for a living might become, in reality only someone with title and “old” money could ever hope to woo someone like Kelly. Daily News columnist Phil Santora complained that Rainier was “not good enough” for Kelly, who was “too well-bred a girl to marry the silent partner in a gambling parlor.” He suggested that the actress, having “been enshrined as a sort of all-American girl who would someday marry the all-American boy and raise a crop of quarterbacks for Yale or Notre Dame,” had let down her American public.

To offer one example of how the news was received elsewhere, the Italian press considered the betrothal a good match, as Kelly “came from a wealthy family,” and had a “rigid” Catholic upbringing. La Stampa occasionally skewered Rainier, but its writers seemed less bothered by his associations with gambling and the outdated notion of aristocracy than by his “shy” and “melancholy” nature; for Italians it seems, the chief concern was that Rainier just wasn’t charismatic enough to ‘merit’ such a beautiful wife.

Most reporters arriving in Monaco to cover the wedding were seeing the principality up-close for the first time. It was far from the storybook place they’d been promised by decades of films, novels and news items. Instead they confronted a faded resort, past both its first and second primes, and peopled by officials completely unprepared to meet the demands of modern media professionals. Though Rainier had personally overseen the conversion of a local school into a makeshift press center, equipped with new typewriters and private phone booths, reporters found the infrastructure sorely lacking.

A Monegasque bartender would later recall that journalist, who spent a great deal of time in the local bars waiting for news to develop, often “became irascible.” There were stories of fisticuffs among members of the press corps. Boredom surely played a big role, since there wasn’t that much solid news to report. Then came an official announcement that of the nearly 2,000 journalists on hand, only two dozen were to be allowed into the cathedral to attend the ceremony.

Kelly’s ocean trip from New York to Monaco and the waiting prince, marked, as the narrator of an MGM newsreel put it, “another chapter in the storybook romance.” On April 4, 1956, Kelly and an entourage of some 70 people had boarded the S.S. Constitution at New York harbor to cross the ocean physically and symbolically linking the United States and Europe. The first European to officially greet Kelly wasn’t a Monégasque, but a Frenchman, and one aligned with the film industry: the mayor of Cannes, where the ship had first docked, and which had rearranged its festival schedule to accommodate the wedding.

The Constitution arrived in Monaco on April 12, issuing several deep blasts from its horn as it came in along the coast from the west. Far too large to berth at Monaco’s harbor, it anchored about a mile from the shore. Kelly would be picked up by Rainier’s yacht.

The cheers of the enormous crowd greeted the actress while a band played “The Star Spangled Banner” and press helicopters and small planes circled overhead. She carried her dog with her, a French poodle. A great deal of fuss would later be made about the oversized hat she wore, which covered her face as she disembarked, denying the press-corps their shots.

It began to cloud over as the wedding party made its way from the dock to a row of cars waiting. Members of the Kelly entourage were taken to the Hotel de Paris, while Rainier and his fiancée went to the Palace. The skies opened as the cars left the harbor. It would rain for the next six days, only letting up on the eve of the ceremony.

The look and feel of the religious ceremony that provided the climax to this months-long story owed much to the influence of Kelly’s studio, MGM, which had dispatched a crew of experts to help stage-manage the lavish event. As one of Kelly’s bridesmaids recalled, “the day, like the bride-to-be herself, was a creation brought to us through the joint production efforts of enormous willpower, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and God.” American and Monégasque flags flew side by side at the Palace.

The studio’s technicians oversaw a dress rehearsal days before the ceremony to ensure proper lighting and sound. A team of MGM hair and makeup staff had accompanied Kelly aboard the Constitution. MGM’s cameras were given prime positioning in the Cathedral of Monaco, alongside four newsreel cameras and four live television cameras.

Television crews had never before been permitted to film a wedding ritual in such close-up detail. Viewers would be offered a priest’s eye view of the ritual and extremely close shots of Kelly solemnly crossing herself and of the presentation of the rings, with the actors positioned to allow for the best angles to bring the intimate event to its international audience.

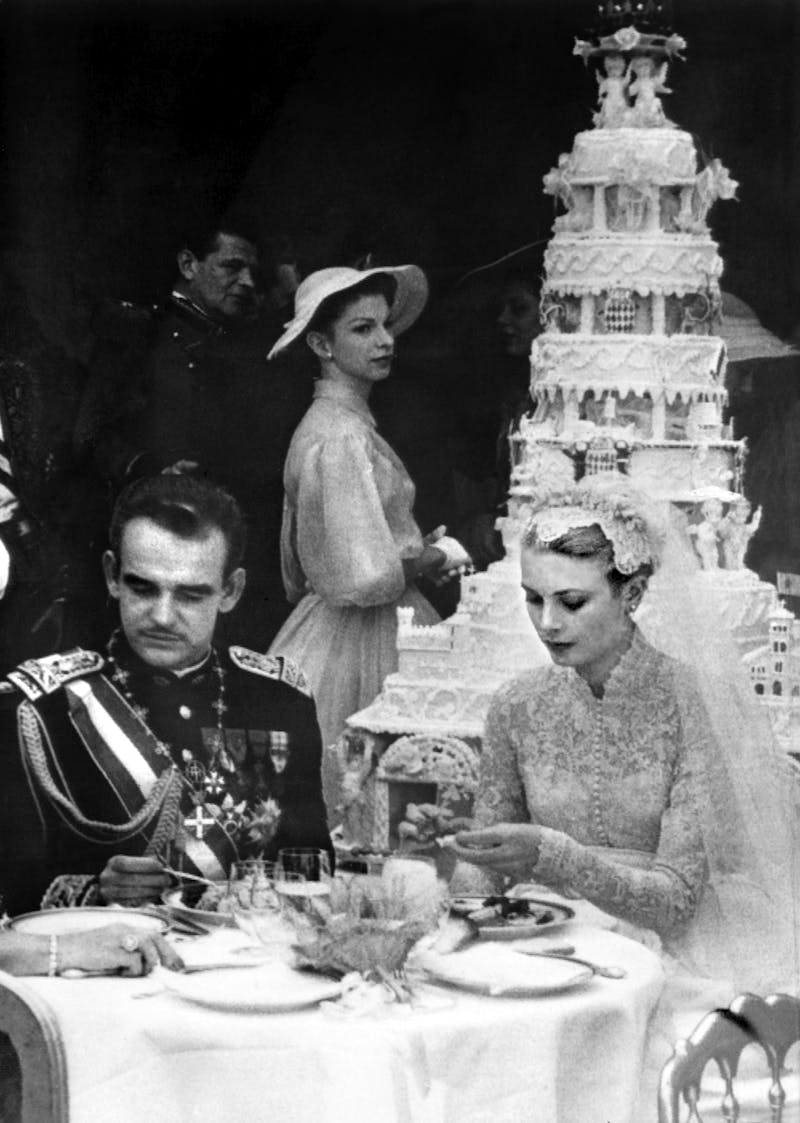

In the outfitting of the bride and groom, aristocratic luxury mixed with Hollywood glamour. MGM lent out the use of one of its top costume designers, Helen Rose. Kelly’s ivory dress, made up of 450 yards of peau de soie, taffeta, silk net, and lace, and with its enormous train, evoked a legacy of fairy-tale princesses; yet Rose used relatively simple lines that were quite fashion-forward for a 1956 wedding gown, offering an updated version of the fairytale. Rainier’s bombastic outfit served as counterbalance to Kelly’s modern dress. Heavily laden with medals, a sash, ostrich plumes, and a scepter, it was an oddly militaristic choice of dress for a Western head of state in that era of postwar reconciliation. (Monaco’s armed forces, it should be noted, numbered less than 70 men.) Rainier had designed the outfit himself, basing the design on uniforms worn by Napoleon’s marshals.

The religious ceremony—there had been a smaller civil ceremony at the palace the day before—began with Kelly entering the cathedral on the arm of her father. They passed by honor guards from British, French, Italian, and American war ships, representatives of Monaco’s two immediate neighbors, its fellow monarchy, and the bride’s home country. The ceremony was presided over by the Papal Legate from Paris, while the Bishop of Monaco looked on. A personal blessing from Pope Pius XII was read aloud during the ceremony. Showing how effortlessly she could move between worlds, Kelly delivered her vows in near flawless French.

Not a single crowned head attended the ceremony, a collective snubbing that underscored the dynasty’s lowly reputation among its would-be monarchical allies. Queen Elizabeth sent Major-General Sir Guy Salisbury-Jones in her stead. The deposed King Farouk and the Aga Khan, both regulars at the Monte Carlo casino, did attend, however. In equally short supply were heads of state from the major Western nations.

Perhaps in recognition of how widely the event would be reported in the international media, France had sent one of its most telegenic representatives, the young François Mitterrand, then serving as Minister of Justice. Italy sent a minor state undersecretary, while the United States, whose officials may have understood the primarily economic rather than political importance of the event, offered as its emissary the hotelier Conrad Hilton, a key figure in spreading America’s hospitality-industry expertise to other countries. Hollywood was represented by the likes of Ava Gardner, Gloria Swanson, and Jack Warner.

Following the ceremony, the couple took a short procession through the principality in a custom-made cream and black Rolls Royce. The car had been presented to the couple as a wedding gift from the people of Monaco, but as the money for such a gift would have come directly from Monaco’s treasury, Rainier and Kelly effectively bought the car for themselves. In Monaco, with its long legacy of motorsport, the choice of post-wedding transport would have been particularly charged. By choosing a British luxury car, the royal couple symbolically aligned itself with Monaco’s monarchical cousin, rather than with neighboring France or Italy, both in possession of healthy auto industries.

The procession ended with Kelly placing her bridal bouquet on the altar of the chapel of Sainte Devote, Monaco’s patron saint. The couple then went to the harbor, where three destroyers (one American, one English, and one Italian) escorted Rainier’s yacht out to the open sea to send of the couple on their honeymoon, cruising around the Mediterranean. The marital ceremony ended with a martial display. While state spectacles have often ended with grandiose displays of modern military might, the wedding in Monaco likely marks one of the few times the firepower was provided exclusively by foreign powers.

The couple sailed off on their honeymoon the same night. The party continued in Monaco, with fireworks and dancing, but the next day it was as though the place were deserted. Observers were struck by how quickly the crowds disappeared; the roads empty where cars had once been double and triple parked, the hotel lobbies empty.

In January when the couple had announced their engagement, a reporter had asked Kelly about her post-marriage career plans. She’d offered a measured response: “I still have a contract with MGM, and I have to do two more pictures. Of course I’m going to continue with my work—I’m never going to stop acting.” Rainier at that point interjected: “I think it would be better if she did not attempt to continue in films…I have to live in Monaco, and she will live there. That wouldn’t work out…She will have enough to do as Princess.”

Kelly, an Oscar-winner in 1954 and once one of the world’s highest paid actresses, never worked in film again, despite repeated requests from Hitchcock and other directors. As Rainier and his advisors no doubt recognized, it’s very difficult to play two roles at once, no matter how similar they might be. The results feel forced. Audiences, seeing too much of the actor’s labor, struggle to suspend disbelief and associate fully with any one character.