“And the first thing they did was segregate me” goes the opening line of Shirley Jackson’s 1941 short story in the New Republic. In the enigmatically titled “My Life with R. H. Macy,” an unnamed Macy’s shopgirl narrates her first day at the store until the moment she abruptly walks off the job forever. Although this was Jackson’s first publication in a commercial magazine, the first sentence is typical of the blunt and uncanny style for which she would later become known. The story also prefigures a career in which she’d frequently be discriminated against and misunderstood. She was 25 at the time. This is how the magazine’s bio line introduced her to the public: “Shirley Jackson, the wife of Stanley Hyman, is living in New Hampshire and writing a novel.”

Shirley Jackson the novelist and Shirley Jackson the wife could not have been more at odds with one another, nor more intimately entwined. While Jackson would come to out-publish and out-earn Hyman—an influential literary critic of his day—Jackson would not escape her dual identity, forced to negotiate the dissonance of being both domestic caretaker and professional author during a period that produced such feminist critiques as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963). (Friedan’s book even condescendingly characterizes Jackson as suffering the false consciousness of considering herself always housewife before writer.) How exactly do we begin to know a life—not to mention a person—so muddled with paradoxes and contradictions?

Jackson’s output is itself divisive. Her fiction walks an uncanny line between documentary and fantasy. It is at once banal and otherworldly, highly specific and symbolic, too close to home and yet still unfamiliar. Readers have difficulty reading her gothic tales alongside the more autobiographical work. When her second novel Hangsaman—arguably her most explicitly autobiographical—came out in 1951, it was widely criticized for being too obscure, as was her subsequent novel, The Bird’s Nest, published three years later. But her domestic memoirs Life Among the Savages (1953) and Raising Demons (1957) were greeted with another form of bewilderment: Why was a prose stylist of Jackson’s caliber wasting her time with such trivialities? Reviewers responded to Jackson’s penultimate novel The Haunting of Hill House (1959) with almost unanimous praise. Even then, readers were unsure whether it was simply a horror thriller or a novel “about” something.

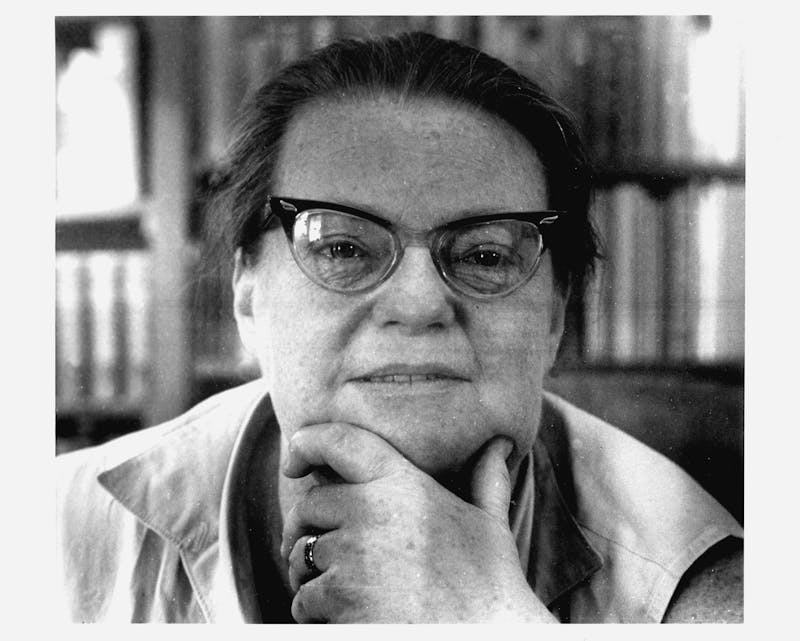

In trying to slot Jackson into one of her many roles—wife or author, popular genre writer or highbrow novelist, mother or witch—critics have repeatedly failed to account for Jackson as a total person, complex enough for sustained and serious study. While Jackson’s works are increasingly becoming accepted as part of the American canon today, her autobiographical fiction still tends to be considered more “minor.” As Jonathan Lethem writes in his introduction to the 2006 reissue of We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Jackson is “both perpetually underrated and persistently mischaracterized as a writer of upscale horror.” That seems to have finally begun to change.

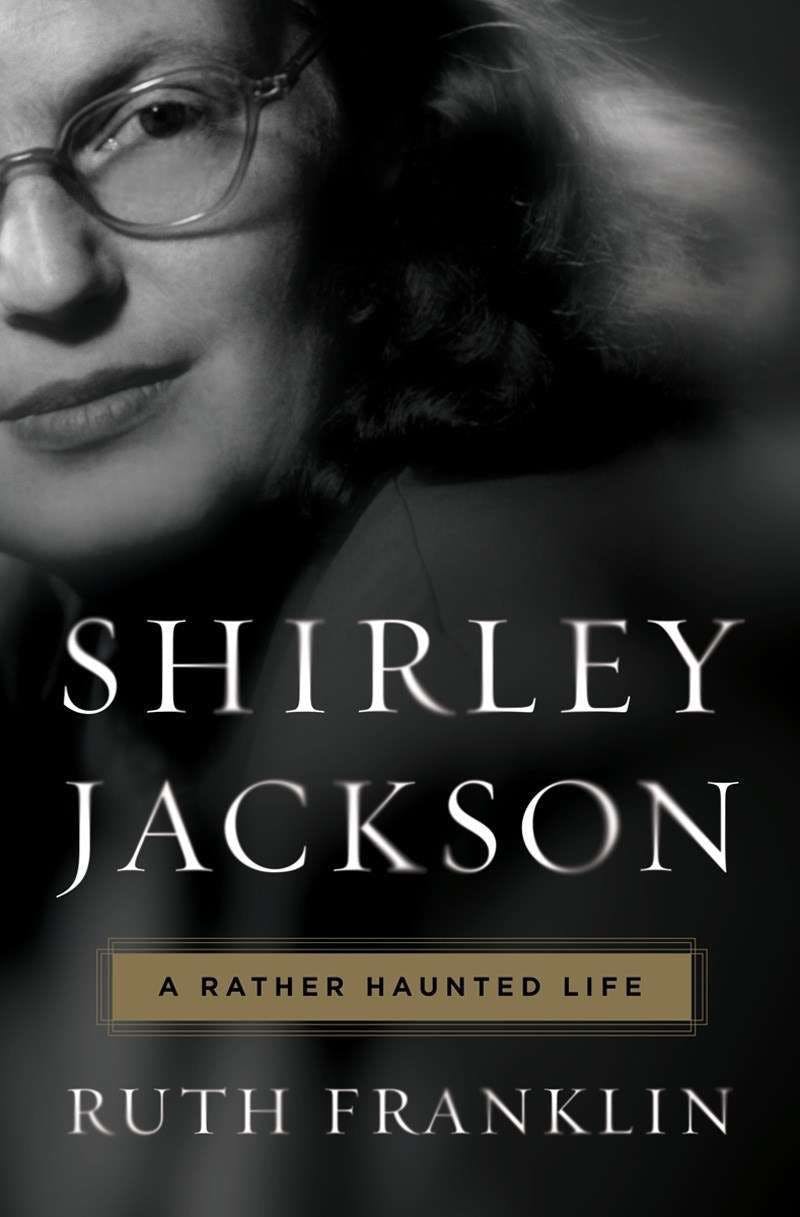

Ruth Franklin’s new biography Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life has been keenly anticipated by both readers of Franklin and Jackson. Over half a century after the novelist’s death, it is perhaps surprising that this is only the second biography of Jackson, considering how autobiographical her writing often was. But having been underrated throughout her life, Jackson is at last experiencing a revival. Elaine Showalter has called her one of the most important writers of the mid-twentieth century; Joyce Carol Oates edited a Library of America collection of Jackson’s work; and the afterlife of her infamous story “The Lottery” remains alive and well in popular culture (see The Hunger Games). A Shirley Jackson biography seems especially timely today, even though Jackson, as with many of her stories, remains somewhat mythically timeless.

The other biography is Judith Oppenheimer’s 1988 Private Demons, which, as perhaps gathered by its title, tends toward a more gossipy and sensationalized portrayal of the author who once billed herself as “the only contemporary writer who is a practicing amateur witch.” Franklin’s is both broader in scope and more measured in its analysis. One of the most prominent literary critics in America today, Franklin’s first book, A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction, explores the line between fiction and memoir—a strangely appropriate companion to a biography of Jackson. For any fanatic reader of Shirley Jackson, A Rather Haunted Life might give you vertigo. It is a biography in which the writer’s understanding of her subject feels, at times, eerily intuitive.

Shirley Hardie Jackson was born on December 14, 1916 in Burlingame, California to Leslie and Geraldine Jackson. While Leslie was an immigrant with an unknown past, Geraldine’s family had been established in San Francisco for a few generations, starting with Samuel Bugbee, a Gilded Age architect who designed Gothic mansions much like the ones his great-great-granddaughter would come to write novels about. As Franklin details, the awkward Shirley was never the conventional socialite daughter Geraldine had hoped for, and a dynamic of disappointment and resentment would play out between them for the rest of her life. When the family moved to New York State, Jackson entered the nearby University of Rochester but withdrew halfway through due to mental problems. A year later, Jackson started college anew at Syracuse University—this time further away, as Franklin observes, from Geraldine’s judgmental eyes.

At Syracuse, Jackson would meet Stanley Hyman, her future husband, lifelong interlocutor, and, at times, harshest reader. Jackson’s first book would be dedicated to “Stanley, a critic.” Both aspiring writers with intense ambition, Jackson and Hyman each immediately recognized a kindred spirit in the other. The story goes that Hyman decided to marry Jackson before he had even met her, on the strength of one of her stories in a class magazine. They eventually began a complicated romance that was both intellectually fruitful and emotionally stormy. Hyman came from an intellectual New York Jewish family and believed in Communism, while Jackson was a lapsed Christian Scientist, obsessed with James Frazer’s Golden Bough. To his credit, Hyman immediately recognized Jackson’s genius. As one of their college friends put it, “He talked a lot but she wrote better.”

It sounds like one of those torrid college affairs that could have ended explosively and nonetheless remained “formative” in one’s memory. Except Jackson and Hyman never quite seemed to end; the at times oppressive atmosphere of their relationship can be felt in Jackson’s prose. During their courtship and for the rest of Jackson’s life, Stanley would be a serial adulterer, moving at first through college acquaintances and, later, instigating affairs with mutual friends and ex-students, while teaching at the then all-women Bennington College. Each infidelity was brief, and always ended with the couple making up, but the incessant cheating was nonetheless detrimental to Jackson’s mental health. Throughout Franklin’s book, one gets a sense that Hyman and Jackson felt somehow compelled to remain together, even as that commitment began to feel, for Jackson, indistinguishable from entrapment.

Though Franklin’s biography does not exactly follow the marriage plot, the conventions of that often-gothic genre did indeed haunt Jackson’s life. Too poor to own more than one typewriter at the start, Hyman naturally commandeered that shared resource; and even when Jackson was earning so much more than Hyman that her income alone paid for their house, Hyman would move Jackson’s own typewriter from their study to the attic because he found her too distractingly messy. (How much Jackson’s admittedly bad housekeeping habits were a reaction to her mother or passive aggressiveness toward Stanley, it’s difficult to tell.) Jackson nonetheless took on the full brunt of housework and childcare, so that, at the time of her death, Hyman still didn’t know how to make a cup of coffee. Franklin muses at one point just how much more Jackson might have been able to do, or write, if she had been relieved of some of these domestic and emotional labors.

Jackson was surprisingly productive and consistent in her output, despite all her personal and professional obstacles. Hyman, on the other hand, struggled to complete his own work, even while being released of child rearing and having all his meals provided for him. Franklin’s chapter on what might be seen as Jackson’s breakthrough work, “The Lottery,” subtly tracks Jackson and Hyman’s inverse trajectories: Hyman’s first book The Armed Vision came out almost at the same time as “The Lottery” in 1948, and unlike Jackson’s instant classic, did miserably in sales. He would not publish another work of literary criticism until 1961, again, to lackluster reception.

Franklin does not, however, portray Hyman as simply the villainous husband of an underappreciated woman writer. She describes how the First World War, the Spanish Civil War, and the Harlem Renaissance influenced Jackson and Hyman in their early years, and she is also careful to convey the couple’s emphatic anti-racism. Her book accounts for the multi-racial intellectual circles they moved in, as well as the perhaps unexpected convergences among different cultural and political spheres. Hyman began a lifelong friendship with Ralph Ellison in 1942, and supported him through writer’s block (Ellison would sometimes write in Hyman and Jackson’s living room) while also offering his editorial guidance. Hyman also introduced Ellison to literary critic Kenneth Burke, to whom Invisible Man is dedicated. Moreover, Ellison’s “Flying Home” and Jackson’s “Behold the Child Among His Newborn Blisses” were published in an anthology titled Cross-Section: New American Writing (1945), which was, for both, their first “appearance between hard covers,” to borrow Ellison’s phrase. It is possible that neither of them would have submitted their stories if not for Hyman’s insistence.

When reading Franklin’s masterful account of Jackson’s life, one senses how profoundly Jackson’s fiction draws from personal experience. The parallels are often startling: There’s a fictional retelling of Jackson’s rendezvous with Dylan Thomas in “The Beautiful Stranger”; or the devastating caricature of an odious male book critic in Hangsaman, which reads like an angry subtweet of Hyman.

Since Hyman’s era, literary criticism has significantly shied away from treating the personal as a kind of usable fact, but Franklin elegantly interweaves anecdote and analysis so that, at times, the distinction almost seems arbitrary. Because so many of the resonances between the life and the work are so literal—a Jewish husband and a wife with a son at x age; or an angry faculty-wife of a unfaithful professor—Franklin’s book reminds us that whether something actually happened or not is not necessarily what differentiates fiction from non-fiction. This is so in Jackson’s own approach to storytelling. As Franklin describes “The Lottery,” Jackson’s stories are “at once generic and utterly personal.”

To be sure, this paradox is also what has made the reception of Jackson’s fiction so uneven. “The Lottery”—Jackson’s now-classic story about a small town’s yearly ritual of choosing a member by ballot to be stoned to death—found outraged readers when first published in The New Yorker. The magazine received such an unprecedented amount of mail about it that the editors eventually released a statement to the press remarking upon this fact. A few of the letters were positive but most, Jackson later recalled, fell under the categories of “bewilderment, speculation, and plain old-fashioned abuse.” One reader claimed that she read the story “while soaking in the tub and was tempted to put my head underwater and end it all.”

“The Lottery” was so powerful that

it even engendered a myth about its own process of coming to life. Jackson

titled her lecture on writing the infamous piece, “Biography of a Story.” Yet

no one really knows its origins, and even Jackson’s version of events—she

claims that she wrote it in one short, inspired burst with minimal edits—doesn’t

quite all add up. The turn around time between drafting and publication date

would have been something like three weeks if Jackson’s timeline is to

believed, but archives of her correspondence show a slower process. As for the

composition of it all at once in only a few hours rescued away from domestic

chores—that still seems to stand to record.

While the world came to recognize Shirley Jackson’s name, it paradoxically began to see less of her. She became ever more anxious about going out in public during her final years, making it hard not only to leave the house or go out in her car (Jackson loved driving), but also somehow difficult to write. When she fell and twisted her ankle in the winter of 1962, she welcomed it as a happy accident, and would not leave the house again until the following spring.

The last two chapters of A Rather Haunted Life, titled “Writing Is The Way Out” and “Last Words,” focus on what Franklin frequently describes as Jackson’s “escape.” Marriage with Hyman had not been easy, and Jackson’s diary entries and (unsent) letters tell a story of a person who often wished to start again, completely unencumbered. The fantasy of running away is everywhere in her late fiction, too, from Eleanor Vance, who goes on a joy ride in a stolen car at the start of The Haunting of Hill House, to Angela Motorman, the significantly-named protagonist of Jackson’s unfinished work, Come Along With Me. Franklin compares Jackson to her escape-artist heroines, who dream that they might “step through a crack and disappear.” On August 8, 1965, Jackson went upstairs to take her usual post-lunch nap and never woke up. It’s as understated an ending as Jackson ever wrote.