Jerry Coyne knows a good protest when he sees one. Once a rambunctious leftist, the esteemed evolutionary biologist recalls traveling regularly to Washington to march for civil rights. He remembers when state police chased him off his own college campus for protesting the Vietnam War. For his most climactic endeavor, Coyne says he tried to post an anti-apartheid petition on the door of the South African embassy, and was arrested for trespassing.

Despite this activist streak, Coyne isn’t sure he’ll attend the March for Science on April 22 (Earth Day), when millions of scientists and their supporters are expected to march on Washington and other cities across the country. He says the march’s message has the potential to “alienate the public.”

“I’m in favor of rights for gay people. I don’t care what bathroom somebody uses. I’m pro-choice,” said Coyne, an occasional the New Republic contributor. “But scientists can’t get involved in that kind of stuff. Science cannot adjudicate issues of morality.”

To be fair, the March for Science isn’t supposed to address issues of morality. “The March for Science is a celebration of science,” according to organizers. “It’s not about scientists or politicians; it is about the very real role that science plays in each of our lives and the need to respect and encourage research that gives us insight into the world...The March for Science champions and defends science and scientific integrity.”

President Donald Trump has indicated he won’t make evidence-based decisions, and that research is not a priority. He has appointed climate deniers to key cabinet positions, including EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt and energy secretary nominee Rick Perry, and reportedly asked vaccine skeptic Robert Kennedy Jr. to lead a commission on vaccines (or autism, depending on the source). Trump has pledged to cut $54 billion in non-defense discretionary spending, the category that funds public research. His rumored frontrunner for science adviser, William Happer, thinks global warming is good for humanity.

How can scientists not speak up for their profession?

“We face a possible future where people not only ignore scientific evidence, but seek to eliminate it entirely,” the March for Science website states. “Staying silent is a luxury that we can no longer afford.”

But with the march occurring in 300 cities across 30 countries, some scientists worry that organizers won’t be able to control the message. The march was, after all, inspired by the Women’s March—an event undoubtedly successful in its attendance levels, but which some criticized as having too diffuse a mission. There’s also lingering sourness over the way the March for Science was hastily organized, at first emphasizing a commitment to social justice that some scientists found off-putting. And if the message is unable to be controlled—that is, if it gets too political—there are worries that the march will undermine the very thing it is intended to strengthen.

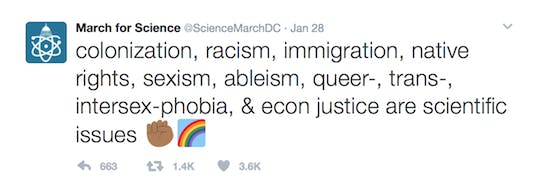

The drama surrounding the March for Science began—where else—on Twitter. In the early stages of planning, organizers took what they considered the most intersectional approach, aligning themselves with a diverse group of other protest movements. “Colonization, racism, immigration, native rights, sexism, ableism, queer-, trans-, intersex-phobia, and econ justice are scientific issues,” an organizer tweeted, just one of many expressions of solidarity with other identity-based groups.

This was not well received in some quarters. Harvard psychologist Stephen Pinker responded that the march “compromises its goals with anti-science PC/identity politics/hard-left rhetoric.” Coyne agreed. “I was pretty appalled,” he said, and cited the march’s website. “Their mission statement was like, all the buzzwords of the regressive left. It wasn’t a march about science, it was a march about identity politics. And at that point, I couldn’t support it.”

Some of the march’s supporters made a point to note that Pinker (like Coyne) is a white man. “A simple call for diversity isn’t radical unless you’re a white man threatened by the end of patriarchy and white supremacy,” BuzzFeed’s Summer Anne Bolton tweeted. Still, the march’s organizers seemed to acknowledge that such intersectionality was fraught for an allegedly nonpartisan march. The tweet was deleted; the website’s mission statement was tweaked to focus less on diversity (to Pinker’s approval); and in late February, the March for Science tweeted an apology for “some problematic tweets we made recently.”

We're sorry for any harm we caused. We're listening, and we're learning.

— March for Science (@ScienceMarchDC) February 24, 2017

March for Science co-chair Caroline Weinberg said the March is still focusing on social justice, particularly when it comes to diversity in the science, technology, engineering, and math fields, which tend to be overwhelmingly straight, white, and male. “The term social justice tends to get people hackled up, but social justice issues tie into science,” she said. “It’s not something we’re turning our back on.” The march is also partnering with green groups like the Center for Biological Diversity and NextGen Climate Action, which are aligned with Democrats in opposing Trump.

Thus, some scientists fear that by participating in a march that appears even slightly anti-Trump, they will feed a conservative narrative that scientists are inherently biased and manipulate data for political ends. At the Conservative Political Action Conference’s only climate change panel last week, panelist Steve Milloy accused the Environmental Protection Agency of “paying for the science it wants,” later asserting that “government has completely corrupted science.” These statements not only went unchallenged, but were met with nods of approval from the rest of the panel.

The biggest concern, though, is that even with perfectly unbiased messaging, the march still won’t accomplish much. “A science march that fosters its own interests—that says vaccines are safe and global warming is real—how is it going to convince those people who don’t believe that already?” Coyne asked. “How is a march going to make them trust scientists any more?”

Coyne believes scientists would be more effective if they started lobbying Congress directly. He also says they should submit more opinion columns; write more letters to the editor; increase their public presence in ways that doesn’t lump them in with the liberal movement.

But most march organizers and supporters don’t appear to be concerned about seeming political. Miriam Kramer, a science writer for Mashable, called “bullshit” on the notion that scientists should avoid political action and bluntly implored scientists to “march for your damn job,” even if it has no impact on the Trump administration’s actions. “Although the March for Science may not change anything about what the Trump administration plans to do in the next four to eight years, it will at least show that scientists—and those who support them—are a sizable group that should not be invisible to those running our country,” she wrote.

If scientists are defensive in the first place, perhaps it’s because of conservative rhetoric portraying them as partisan hacks. That’s not likely to change. Regardless of whether there are anti-Trump signs at the march, outlets like Fox News and Breitbart will likely characterize it as further proof that scientists are hopelessly biased and untrustworthy. Their viewers might buy it, but most Americans do not. Public trust of scientists is high: 76 percent of Americans have “at least a fair amount of confidence” in scientists, the highest level of trust in any profession behind doctors and members of the military.

Perhaps, then, the real value of the march will not be converting the non-trusting public, but educating them. Seventy percent of Americans cannot name a living scientist. They don’t know what the $70 billion in non-defense spending for research is used for; nor do they know how that research contributes to their lives. And there are countless ways it has. Federally funded research has led to the development of everything from Google’s search algorithm to advanced prosthetic limbs to Lactose-free milk.

“We think it’s important to have a huge part of our post-march programming be connecting scientists to people,” Weinberg said. That’s why the march in D.C. will be followed by a teach-in on the National Mall, where speakers will talk about their research “in a more intimate way than most people are used to,” she said.

That may wind up being the most impactful part of the March for Science: Providing a public platform for the work that so often goes unnoticed. Marshall Shepherd, a meteorologist who hosts a talk show on the Weather Channel, has often cautioned scientists against political speech. But he said he supports the March for Science if it can stay focused on what science does for society—and perhaps humanize his colleagues to the rest of the country.

“I think scientists are too often seen as people with agendas,” he said. “But in my case, my work with weather and climate is just because I love my kids and worry about their future. I actually hope that I am wrong about what I see, for their sake.”