For centuries, Europeans saw the bear as an intermediary between the human and animal worlds, promising superhuman might but also threatening descent into the inhuman. Medieval warriors venerated the animal in frenetic rituals, hoping to take on its fearsome power; male bears were said to kidnap and rape young women. Over time, the European bear was tamed, but it maintained its symbolic power, notably as a stand-in for Russia: In 1984, Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign ran an ad showing a bear roaming the forest. “There is a bear in the woods,” a voiceover said ominously. “Some people say the bear is tame. Others say it’s vicious and dangerous. Since no one can really be sure who’s right, isn’t it smart to be as strong as the bear?” The ad closed with the silhouette of a man on a grassy slope, staring the bear down.

The end of the Soviet Union placed this symbolic creature at the center of a political struggle for a new way of life in the former Eastern bloc. Some Slavic countries had maintained the tradition of the dancing bear into the twenty-first century, long after it had been abolished in Western Europe. But as Bulgaria prepared to join the European Union, it had to begin the process of abolishing bearkeeping. An Austrian animal rights organization called Four Paws opened a bear park in Belitsa, outside Sofia. It planned to free Bulgaria’s dancing bears from the whip, the nose ring and the chain lead, the vodka and candy that its keepers used to pacify it. The dancing bear, forced by violence into a grotesque imitation of human behavior, would be remade into a dignified wild animal that walked on all fours, returned to the firm ground of its natural habitat.

But animals raised in captivity can rarely survive in the wild, and there is not much wild left in Europe, where animals have little choice but to live in a world shaped by humans. Bulgaria’s liberated bears would spend the rest of their life in luxurious captivity, the components of a wholesome, all-natural bear diet hidden for them in their park by their new, more enlightened keepers. They would have to be taught how to move, how to hibernate, how to copulate (though they would also be sterilized, as they were unfit to raise young). Idealistic humans would try to teach the animals how to be free, though for the bears genuine freedom would have meant death.

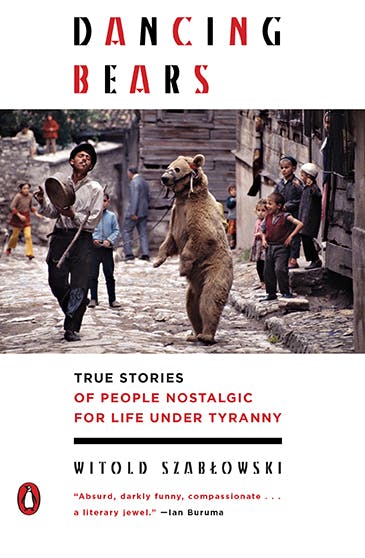

In Dancing Bears: True Stories of People Nostalgic for Life Under Tyranny (this subtitle was added for the American edition), Polish journalist Witold Szabłowski sees the bears’ liberation as a metaphor. He calls the Belitsa bear park a “freedom research lab,” comparing it to the post-Communist world. “Ever since the transition from socialism to democracy began in Poland in 1989,” he writes,

our lives have been a kind of freedom research project—a never-ending course in what freedom is, how to make use of it, and what sort of price is paid for it. We have had to learn how free people take care of themselves, of their families, of their futures. How they eat, sleep, make love—because under socialism the state was always poking its nose into its citizens’ plates, beds, and private lives.

The retired bear has moments when “freedom starts to cause it pain,” and it reverts to its dancing, begging ways, “as if it would prefer that its keeper come back to take responsibility for its life again.” In the same way, Szabłowski claims, the postsocialist citizen faces a constant temptation to lapse back into dependency, leading either to nostalgia for socialism or to a fondness for populist demagogues, such as the right-wing nationalists who have come to power in Poland and Hungary.

Szabłowski is trying to account for a reality that has been widely observed in recent years: Both his book and The Long Hangover: Putin’s New Russia and the Ghosts of the Past, a new book by the English journalist Shaun Walker, examine how people in postsocialist societies turn to the past in their search for a refuge from the painful realities of the present. Szabłowski has compiled a set of case studies full of tensions and contradictions, but he uses them to draw a simplistic conclusion: Freedom is scary. Walker focuses on the political uses of memory: The positive memory of Soviet victory in World War II and the repressed memories of the Gulag, mass deportations and executions, and less glorious wars. While Szabłowski looks for one explanation, Walker charts the complex factors—including decades of violence, postsocialist inequality and deprivation, and a lack of a positive cultural identity—that have created the phenomenon, much discussed but often poorly understood, that we call nostalgia for socialism.

Dancing Bears begins with Gyorgy Marinov, an elderly Roma man who is about to lose his bear, Vela. “I loved her as if she were my own daughter,” Marinov laments. “As God is my witness, I loved her as if she were human.” Bulgaria’s dancing bears didn’t belong to the state or to just any Bulgarians. Bearkeepers were most often Roma, who have for centuries been wanderers, entertainers, outsiders, subject to intense discrimination and more often called “Gypsies.” (Szabłowski uses the latter term.) The story of the liberation of the dancing bears is inextricably entwined with the story of anti-Roma discrimination, which peaked with Hitler’s campaign to exterminate the Roma in the 1940s and reasserted itself with the end of Communism and the end of guaranteed employment, housing, and medical care that had mitigated the effects of anti-Roma bias.

Marinov and his family acquired Vela in the early 1990s, when Bulgaria’s collective farms collapsed along with Communism. Marinov lost his job as a tractor driver and decided to become a bearkeeper, like his brother, father, and grandfather before him. He had been raised with bears and knew all the songs and tricks of the trade. He used his severance pay from the collective farm to buy a bear cub from a nature preserve, taking her home on the bus. With the necessary permits in hand, he began training Vela to stand on her hind legs, to kiss a lady’s hand, to imitate famous Bulgarian athletes, and to give massages or lie on top of the very sick, absorbing and defeating their illness. Marinov and Vela traveled from village to village, earning a decent living. He said that the only time he ever hurt her was the day he stuck a red-hot bar into her nose, making a hole for the ring that he would use to steer her.

The very last bearkeepers in Bulgaria were members of an extended Bulgarian Roma family, the Stanevs. In June 2007, after a seven-year battle, they were surrounded by journalists, animal rights campaigners, and locals who wanted to witness the end of the tradition of dancing bears. The people from Four Paws announced, “The Stanevs’ animals are the last dancing bears in the civilized world.” To free Bulgaria of dancing bears, they implied, was to free Bulgaria of barbarity. Facing the loss of their livelihood, the Stanevs did their best to extract as much money as they could from the journalists in exchange for photos.

A Bulgarian Four Paws employee, Vasil Dimitrov, speaks to Szabłowski with derision of the “dumb, grasping Gypsy”—who is, in his account, as greedy, cunning, and stupid as the bears of European fables. He perceives the bears, on the other hand, as “intelligent, noble, and regal. Nature in its most perfect form.” He admits frankly that he has no interest in the future of the bearkeepers: Let a Roma rights NGO tend to them. The Belitsa welfare line is full of Roma, and Belitsa residents ask awkward questions about the price of the park: Why doesn’t anyone pay for strawberries and dentistry for the local humans? “I’m sorry I wasn’t born a bear,” the former mayor of Belitsa grumbles, since the park’s budget is more generous than that of his town.

Szabłowski’s interviews yield fascinating material, but he often declines to take his subjects at their word, both in Bulgaria and beyond. In the second half of his book, he leaves Bulgaria to report from a number of other postsocialist countries, where he draws parallels between the local inhabitants and the Four Paws bears. In Cuba, a woman named Mirurgia tells him that she wishes Fidel Castro could rule for another lifetime, saying:

Thanks to him, we’re the last country that isn’t led on a string by the USA. We have a superb education and health-care system. Nobody’s dying of hunger here. You only have to look at Dominica, or Haiti, which are on America’s leash. They’ve got nothing to eat there. But in the stores here you can buy anything.

An avid Communist, Mirurgia denies the many faults of the Cuban system, and Szabłowski sees her merely as a woman who has been conditioned to praise an authoritarian regime. But Cuba’s accomplishments in education and health care are indisputable, as is the stark contrast between Cuba and its neighbors. The World Health Organization cites Cuba’s primary health care system as one of the most effective in the world; according to the World Bank, Cuba’s life expectancy is now equivalent to that in the United States and its infant mortality rate is lower. It seems unfair, then, for Szabłowski to suggest that Cubans are like dancing bears, drunken captives to an abusive master.

Widespread dissatisfaction with the capitalist present is one of the main sources of nostalgia for the socialist past. Szabłowski’s reporting highlights the crevasse that opened between rich and poor in many postsocialist countries. He interviews an elderly Polish woman who left her freezing cottage and embarked on a quixotic trip to Strasbourg, having heard that the seat of justice there could help people cheated by the Polish state. Turned away at the doors of the court, she made her way to London, where she took up residence in Victoria bus station. For her, “freedom” has meant destitution, exile, homelessness, an unceasing sense of outrage. Some of Szabłowski’s Ukrainian interview subjects think wistfully of what they imagine as a kinder, gentler Soviet world, while others hope that EU membership (which was never really on the table for Ukraine) might bring prosperity, which they imagine in a socialist-nostalgic mode: collective farms, only privatized.

In Estonia, Szabłowski documents the cruel treatment of the country’s sizable Russian minority after the fall of the Soviet Union. Many Russians who had no desire to return to Russia were denied Estonian citizenship because they could not pass a difficult Estonian language exam. (Szabłowski shows sympathy for the plight of these stateless people but does not make much effort to fit them into his larger argument; his book is more observation than analysis.) At the time of Szabłowski’s visit, there remained enclaves of Estonia that were entirely Russophone; it is not easy for a middle-aged person to learn Estonian, a Finno-Ugric language with 14 tenses, and yet fluent Estonian became a requirement for many jobs. Some Estonians view the Russian minority as a fifth column laying the groundwork for another Russian invasion. This threatens to become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as discrimination primes Estonian Russians for the virulent political propaganda exported by Russia. Treat a man like a bear for too long, and he might maul you.

In The Long Hangover, Shaun Walker steers mercifully clear of bear analogies. Walker spent the last decade as a Moscow correspondent, first for the British newspaper The Independent and then for The Guardian; his reporting has been distinguished by an evenhandedness and open-mindedness that have become sadly rare in coverage of Russia and Ukraine. The Long Hangover offers a fine-grained portrait of post-Soviet nostalgia and resentment, showing how much post-Soviet dysfunction grows from trauma rather than from an inability to cope with freedom.

As part of his campaign to restore Russia’s former status as a world power, Putin fostered an obsessive focus on Russia’s defeat of the Nazis in World War II. Walker shows how Putin has used this cult of victory to promote a unifying “national idea” of Russia’s enduring strength and glory and to make Russians feel proud rather than ashamed, a dramatic turn after the rudderless misery of the Yeltsin years. Today, the heavily redacted official memory of the war functions as a distorting lens for Russia’s more recent military engagements, turning any conflict into a story of Russia’s heroic battle against its enemies. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its intervention in Eastern Ukraine, for instance, became a struggle against “Ukrainian fascists,” a reenactment of Russia’s victory over the Nazis.

Some of Walker’s most surprising case studies are of ethnic minorities whose historical narratives have been subsumed by Russia’s victory cult, and who have been recruited, seemingly against all odds, to fight on the side of their oppressor. The Chechens were colonized first by the Russian Empire and then by the Soviets; in 1944, they were one of several ethnic minorities accused of collaboration with the Nazis and deported en masse, often dying in the process. (This is one of the many dark sides of the Soviet experience of World War II, and one that has been energetically suppressed in Russian and even Chechen public memory.) Yeltsin attempted to quash Chechnya’s post-Soviet bid for independence with a devastating assault that included war crimes against Chechen fighters and civilians. Putin took up this cause, killing off the Chechen independence movement for good and funding the reconstruction of Grozny, the Chechen capital, in exchange for the loyalty of his chosen Chechen warlord clan, the Kadyrovs.

Many Chechen independence fighters went over to the Kadyrovs’ side—this was the price of survival. But they continued to carry the pain of the unmourned deaths of family members and friends who had been disappeared, tortured, raped, mutilated. Walker interviews one of these men, Apti, who tells him, “We feel a heavy burden and a void, an overwhelming void.” Apti went on to fight in one of the pro-separatist Chechen battalions in Eastern Ukraine. It is shocking to imagine that, with his whole life ravaged by Russian state violence, he could fight on the side of the Russians; but Walker’s portrait of the unresolved anguish of a generation of Chechens makes it easier to understand how a person can sustain this level of contradiction.

Walker unearths another near-miracle of cognitive dissonance in his investigation of the Gulag archipelago, which remains outside the purview of Russian national memory. (Schoolchildren are taught that the Gulag was an “unfortunate side-effect” of the military and industrial achievements of Stalinism.) In the late 1980s, a Kolyma resident named Ivan Panikarov began collecting artifacts from the ruins of Gulag sites. Thwarted in his efforts to start a more formal museum, he used his apartment as a place to display his many discoveries. Today, it is one of only three Russian museums devoted entirely to Stalin-era repressions. Panikarov has few visitors, most of them foreigners, but Walker is surprised to find him less than enthusiastic about his visit. Soon Panikarov bursts out with the reason for his irritation: “You come here and you’re looking for negative things. It used to be fashionable to say bad things about the USSR, now it is the same thing again. People fell in love in the camps, people got pregnant, it wasn’t all bad.” He offers his interrogation files as proof of the careful due process observed by Soviet authorities.

Panikarov’s outrage offers a caricature of public memory in Russia, where any negative treatment of past events is interpreted as Western slander. For decades, this man has lived surrounded by rusted spoons sharpened into knives, teapots made from tuna tins, bullet casings—and yet he resents it when a foreign visitor is disturbed by these artifacts of human suffering. Walker listens patiently to Panikarov’s drunken rants in defense of Stalin, remarking stoically, “I liked Panikarov; the way he had built up his collection was quietly impressive, and there was something almost charming about his irritable demeanor.”

Walker’s reports from Crimea and Eastern Ukraine offer particularly powerful illustrations of the political importance of nostalgia for the Soviet Union. One frustrated Crimean man named Vladimir explains, “Until the Soviet Union fell apart, I didn’t even think along the lines of different countries or nationalities, and suddenly, it was all gone. And I turned into a nobody overnight. I had no idea what the point of life was; there was no sense of why you were raising your children, what the point of anything was.” This nostalgia isn’t necessarily about the virtues of Communism as a socioeconomic system. It’s a search for lost time, a longing for a vanished homeland and a coherent identity. Above all, it is about the pain and unhappiness of what came after, including the blatant economic inequality that resulted from privatization.

That pain can transform the Communist past, with all its darkness, into a sort of fairyland, an impossibly good place. It can be accompanied by other, more sinister forms of magical thinking. Vladimir, the frustrated Crimean, joins a pro-Russian brigade, stuffs his mind with outlandish conspiracy theories (one is that the Queen of England has a stone made by Jews under her throne, which is what makes her so powerful), and shows Walker his new “talisman”: a chrome pistol engraved with a thank-you message to Vladimir from the Russian Defense Minister. Now, it seems, Vladimir has found his purpose, even if Russian annexation has made the conditions of everyday life substantially worse.

Alexander Khodakovsky, a perverse genius of the Eastern Ukrainian separatist movement and the most intriguing of Walker’s gallery of characters, is nostalgic for the noble, purposeful suffering of the Soviet past. He explains that his childhood in the mining and factory region of Donbass in the 1970s and ’80s was characterized by deprivation, improvisation, and industrial achievement of an awe-inspiring scale. “Even though life was hard,” he tells Walker, “there was a kind of point to life, which I guess was built as much on being contrary as on any achievements. We didn’t care what people in the West thought of us, and we took a masochistic pleasure in not caring.” Khodakovsky tells Walker that his childhood revolved around the memory of victory in World War II: At 14, he and his friends found a piece of red fabric and took turns pretending to storm the Reichstag.

When the Soviet Union fell, its planned economy fell along with it. This struck a particularly severe blow to Donbass—which was now a part of Ukraine, though many residents had only a weak affinity, if any, for the Ukrainian national project. In the 1990s, Donbass experienced brutal violence in connection with the concentration of resources among a tiny elite, even as the masses struggled to earn enough to put food on the table. This disenfranchised, disappointed majority eventually helped give the separatist movement critical mass in Donbass; Walker shows clearly that Russian intervention was only part of the story, albeit a crucial one.

Khodakovsky expresses regret over the end of Communism as an economic system, arguing, “Market relations just push people away from each other.” He condemns the corruption of post-Soviet Ukraine’s government, remembering the Soviet Union (inaccurately) as a place of greater honor. But he understands that Moscow is only manipulating nostalgia to serve its own capitalist ends and that a genuine resurgence of socialist ideas would pose a serious threat to the Russian political establishment. This means that separatist leaders like him must stamp out any threat of genuine socialism, even as they encourage symbolic Soviet nostalgia. Those who stray too far from Moscow’s line have a way of being blown up or shot under mysterious circumstances. Meanwhile, the Russian government has sponsored a mock-up Reichstag for a park outside Moscow, so that young people can practice storming it.

With their wide-ranging reportage, Walker and Szabłowski depict a postsocialist reality that is almost mind-bogglingly complex, rife with contradictions, absurdities, and arguments without end. The two books are testaments to the importance of documenting a broad spectrum of experiences, of hearing people out even when their ideas and conduct might seem repugnant or incomprehensible at first glance. As both authors note, recent developments in European and American politics have made clear the dangers of ignoring the desires and resentments of a large swath of the population.

When we leave Khodakovsky, he is at risk of Russian assassination, with a hollowed-out look, but he refuses to leave Eastern Ukraine or to admit to any regrets. “We’re tired of being an experiment,” he tells Walker. “Our people were used and ignored for years on end, and then they had a small taste of what it’s like to be part of something real.”