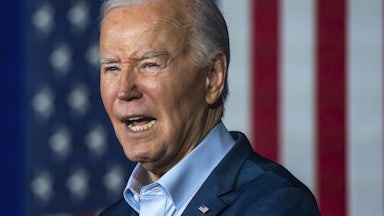

Failed wars have

bookended President Biden’s political career. He was first elected to the U.S.

Senate in 1972, when the futility and misguidedness of our war in Vietnam were

clear. He ran as an opponent of the war but balked at full-throated

condemnation, saying, “I wasn’t against the war for moral reasons; I just

thought it was a stupid policy.”

In 2021—the year Biden became president—America continues to fight a different but equally self-defeating conflict: the “war on terror.” As chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, in 2002, Biden played a key role in the American response to 9/11, and voted for the invasion of Iraq. Since then, Biden has acknowledged that his vote for the war was a “mistake” and maintains that he was misled by President George W. Bush.

Biden’s five deferments from service during Vietnam insulated him from directly experiencing the inhumanity of war. As veterans of the Vietnam and Afghanistan conflicts, we hope that he will learn from history and exhibit better judgment as president and commander in chief than he has in the past, and put an end to a war that the majority of veterans believe has never been worth fighting.

This will require a dramatic transformation of America’s foreign policy. Fortunately, Biden has shown some indications that he is ready to take the brave steps that are needed. In his first major foreign policy speech on February 4, he announced that he would end support for political violence in Yemen, rebuild international alliances, and stiffen America’s response to Russian aggression. Furthermore, the Biden administration is confronting racial and political extremism in the military and aims to close Guantánamo Bay prison, where prisoners, once targets of a government-sanctioned torture program, remain subject to indefinite detention without trial.

We commend these changes.

Absent from this discussion, however, has been a detailed plan to end the failed war on terror or curtail America’s excessive military spending. Moreover, Biden was not clear about what he meant by “America is back.” We hope this does not merely imply a foreign policy Groundhog Day, where America will get four more years of war.

From our hard-won experiences in two disastrous foreign wars, we offer five principles that, we believe, can save our country from repeating the same mistakes for a third time.

1. Reassert the core constitutional premise that Congress, not the president, decides whether America goes to war.

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war. However, since 1942, Congress has eschewed all responsibility for war, delegating it to the executive branch. For almost a century, the United States has replaced legal declaration of war with “authorization to use military force,” or AUMF, with predictably disastrous results. Although originally intended to be narrow in scope, AUMFs have become bloated vehicles for sweeping presidential authority, facilitating political violence unbounded by constraints of geography or timeline.

To redress the resulting imbalance of power between the executive and legislative branches of government, President Biden should push for the repeal of the existing AUMFs and reaffirm Congress’s constitutional war powers. More boldly, any future declarations of war should include a “sunset clause,” forcing Congress annually to reconsider and reaffirm the decision to prolong conflict, giving the American people the democratic recourse to fire representatives who vote the wrong way.

This step would help to protect our servicemen and women from having their service misused by shifting the default American posture, which favors extending war through indecision and sheer inertia.

Biden seems to be moving in the right direction on this issue. Earlier this month it was reported that the administration is seeking to repeal the AUMFs that have prolonged the war on terror and replace them with a “narrow and specific framework” for fighting terrorist threats.

2. America must stop waging foreign wars of aggression—especially when they lack a coherent strategy.

In an uncanny case of wartime déjà vu, both the Pentagon Papers and the Afghanistan Papers showed that American military and civilian leadership were misleading the American public for years and hiding humiliating strategic failure with rosy pronouncements of progress. Both wars were not only morally bankrupt in their execution but also unwinnable. And the military was complicit in hiding unmistakable evidence of their futility.

In both wars, policymakers and military leaders arrogantly assumed that American military might was irresistible, while sacrificing lives and resources to occupy ground that had no strategic value and was quickly abandoned. Vietnam’s Hill 881 North, near Khe Sanh, was assaulted by Marines three times in 1967 and 1968 with heavy casualties but was occupied for a total of only four days. Khe Sanh Combat Base itself was abandoned and blasted out of existence by American engineers shortly after almost 300 Marines lost their lives and 2,500 more were wounded to hold it against relentless North Vietnamese Army artillery and rocket attacks between January and April 1968.

In Kandahar Province, Afghanistan, Erik was part of a mission nicknamed “Operation Highway Babysitter,” in which the infantry secured the road, allowing logistics convoys to resupply the infantry—all so that the infantry could secure the road, so that the logistics convoys could resupply the infantry.

Worse, whenever a road was destroyed—since protecting all the roads, all the time, was impossible—American forces would pay Afghan construction companies to rebuild it; in turn, the construction company would often pay a protection tribute to the Taliban; then the Taliban would buy more bomb-making materials to destroy the road—and U.S. vehicles.

We were, indirectly but also quite literally, funding the Taliban to kill us.

3. America must stop dehumanizing people “on the other side.”

As violence escalates and comrades are killed in conflict, all wars breed hatred of the other side. However, willful miseducation and racist indoctrination led directly to massive mistreatment, injury, and death of civilians in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. The racist slurs may have evolved over the decades, but the attendant contempt and dehumanization are the same: American troops would never be permitted to treat Americans the way they treat their supposed enemies.

In Vietnam, Ted was taught that “Orientals” have less regard for human life than we do. In Afghanistan, Erik received some advice from a veteran noncommissioned officer: “All these people from Muslim countries—all they understand is force. You haven’t been there yet, sir, but you’ll see. Stubborn motherfuckers are too stupid for anything else.” He also said, “You can’t treat them like people because they’re not.”

“We have shot an amazing number of people,” said General Stanley McChrystal, the former American and NATO commander in Afghanistan, “but to my knowledge, none has ever proven to be a threat.” This outcome is inevitable in a counterinsurgency where soldiers are caught up in slippery-slope thinking: “Since the enemy is always evil, and every Afghan is sort of the enemy, then every Afghan is sort of evil.” If McChrystal’s “insurgent math” is correct—that for every innocent person you kill, you create 10 new enemies—then America’s terrorism eradication strategy promises only never-ending war.

Marine Vietnam veteran Karl Marlantes says, “I didn’t kill people, sons, brothers, fathers. I killed ‘Crispy Critters.’” To look through the optic of your assault rifle and take aim at another person—to make others “killable,” to pretend that “they deserve it”—ensures that peace and justice will never be achieved.

4. Vigorously prosecute war criminals.

There is no such thing as war without war crimes.

Thousands of Vietnamese were forcibly removed from their ancestral villages to refugee camps. Many others did not have that luxury. An Americal Division platoon massacred 500 mostly women, children, and old people at My Lai in March 1968. The U.S. established extensive “free-fire zones,” in which troops were encouraged, even ordered, to “shoot anything that moves.” The U.S. military leadership and government largely covered up or excused these atrocities. As a “rear-echelon motherfucker,” Ted did not have much opportunity to inflict serious physical harm but admits “laughing to see the terrified faces below when, on helicopter rides, we strafed (without shooting) Vietnamese working in their rice fields.”

American soldiers in Vietnam and Afghanistan kept finger bones, leg bones, teeth, ears, and skulls as sick war trophies. The U.S. Army kept images of soldiers smiling, posing over murdered civilians, one a 15-year old boy, under “lock and key out of fear it could result in a scandal even greater than Abu Ghraib.”

Erik was keenly aware of war crimes that occurred during his deployment to Afghanistan. The Stryker unit that replaced him at FOB Ramrod was responsible for a series of despicable civilian murders. On September 9, 2010, CNN reported, “According to the military documents, Staff Sgt. Calvin Gibbs and four other soldiers were involved in throwing grenades at civilians and then shooting them in separate incidents. Three Afghan men died.”

Erik and his platoon witnessed a pair of OH-58 Kiowa helicopters shoot up a series of Afghan homes, without having positive identification on weapons—a requirement in the military’s rules of engagement—resulting in visual confirmation of dead civilians. Rather than confronting this reality, Erik’s unit falsified reports, annotating these deaths as “Unknown.” It is unclear how many hundreds—or thousands, or tens of thousands—of similar incidents took place.

We hope that President Biden’s announcement, in his first week, of a Defense Department inquiry into war crimes during the war on terror presages stricter enforcement of the international rules of war, greater transparency regarding criminal acts, and severe punishment of transgressors.

5. Reallocate public dollars to projects with higher return on investment.

How do you tally up the true cost of war? Perhaps we consider the number of dead, injured, or traumatized: for Vietnam, this meant the death of two million Vietnamese civilians; 1.1 million North Vietnamese soldiers; 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers; and 58,000 U.S. servicemen. The war on terror has brought the death of more than one hundred 9/11s’ worth of civilians and more than 7,000 U.S. troops. In both wars, thousands more suffered grievous physical and psychosocial wounds.

However, this simple listing of tragedies does not capture the full cost, which requires us to consider what might have been instead. It requires imagining the negative space—the hole in the universe created by the absence of people—and the substitution of physical pain and disability for health; or of spending trillions to create war debt instead of putting those funds to better use almost anywhere else.

The war in Vietnam, in 2019 dollars, cost the U.S. $844 billion. For this price tag, the U.S. could have doubled current annual spending for low-income housing for the next 16 years, paid for a year’s worth of groceries for 100 million U.S. households, or sent a $2,500 stimulus check to every American.

The war on terror was even more costly. With the $6.4 trillion spent on this war, America could have paid the $1.6 trillion bill on all student debt in the U.S., provided an entire year of free health care to every American—$3.5 trillion—and had just enough left over to hire Beyoncé for a private concert, every day, for the next 2,000 years.

For years, our nation has been spending a multiple of Afghanistan’s gross domestic product—to protect us from alleged threats from Afghanistan. Why? To fail at making it a modern democracy? Can we finally agree that this use of funds is unwise?

By learning from the conflicts bookending his long life in politics, President Biden has the golden opportunity to put our country on a new, safer, and more just course in the world. If he succeeds, the future of American foreign policy would be filled with real promise, not just false promises.