When René Magritte was a little boy growing up in Belgium in the early 1900s, he had a friend called Raymond who lived a few doors down. Raymond recalls going over to play at the Magrittes’ house, where René’s father Léopold kept a room full of “white metal containers of Cocoline”—a new, coconut oil-based form of margarine which he sold for work—“and advertising posters, too.” Raymond remembers the Cocoline well, he once said, “because René and I played with it, climbed on it, made tunnels through it, and we were coated, coated in it, it was like lard,” and he got in big trouble.

This image, of two little boys absolutely spackled with goo, appears on page 11 of Alex Danchev’s new biography, Magritte: A Life, and would not leave my mind until I had turned the final one. It seems to contain everything about the Surrealist painter’s life and work, in miniature. For one thing, it wouldn’t have happened without the extreme laxity of René’s father: Magritte and his brothers were hellraisers, Danchev explains, who showed all the local kids pornography, frequently yelled “Fire!,” and were rumored to have killed a donkey. And yet he grew up into a painter whose ideas are precise and elegant, and a man who wore bowler hats every day and lived a punctilious and bourgeois life in a Brussels suburb.

It seems like a contradiction in terms, but isn’t. The connections that animated Magritte’s freakish imagination are there, in the graphic language of the Cocoline containers and posters, which predict his graphic design practice, Studio Dongo, and the Cocoline itself—a substitute for a substitute, neither solid nor liquid—presages Magritte’s love of making the ordinary grotesque. But most of all, it’s the fact of play.

For all the grown-upness of

Magritte’s artworks, with their highbrow symbols and bowler hat formality, they

have a naughtiness about them, and Magritte had a naughtiness about himself, Danchev

suggests, a quality that uses a child’s respect for

nonsense to break apart the ordinary function of symbols and words. Underneath the apparent respectability of his paintings, so

smooth in their rendering of elegant references to semiotics and psychology, is

a bad child, uncatchable and still uncaught, writhing with glee in the surplus

fat of the twentieth century.

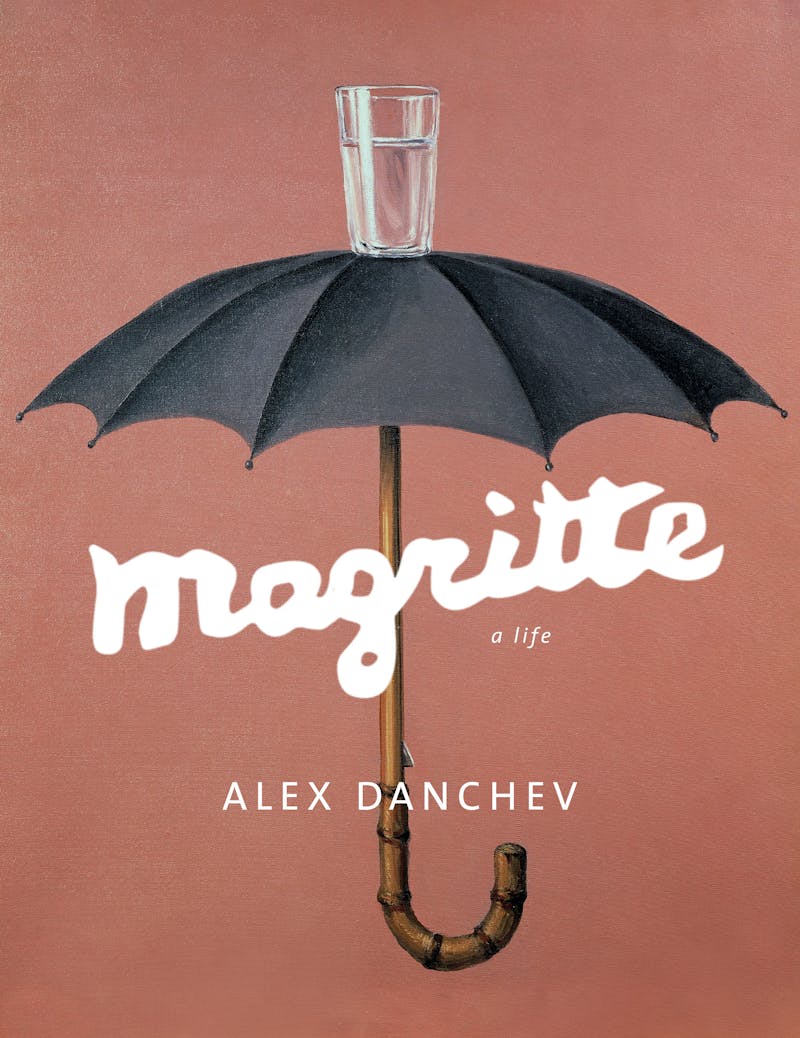

There is a “temptation,” Danchev writes, “to underestimate Magritte on account of his extreme legibility.” By this he means that Magritte’s work is so famous as to be ubiquitous, because, as the book also explores, he was such a crucial forerunner to the visual puns of commercial advertising. There’s a Magritte couch gag on The Simpsons, Danchev notes.

In 1950, deep into his career, which began seriously in the 1920s with Le jockey perdu (“The Lost Jockey”), Magritte made a painting called Perspective II: Manet’s Balcony. It refers to Édouard Manet’s 1869 painting The Balcony, in which three beauties, two women and a young man, cluster around a window, looking out. In Magritte’s version, there are four coffins on the balcony, one sitting on a chair, its “knees” bent. Although Magritte’s word paintings, like his 1929 La Trahison des images, which captions a pipe with “ceci n’est pas une pipe,” are marginally more famous than this one, the Manet work encapsulates the Magrittian method well. It’s funny, because coffins are wooden and don’t sit, as dead people also do not, and because it does something amusing to the dignified subjects of the original painting. It simply contradicts them, and Manet’s vision of them.

Far from underestimating Magritte, Danchev’s picture of him is pointillist and enormous in scope. It is full of shock, for the casual Magritte fan who knows little about his life. His childhood was raucous and unsupervised. When he was 13, his mother drowned in a nearby river in an apparent suicide. She was recovered from a river after 17 days, reputedly with her “nightdress over her face”—a moment Danchev connects to the veiled figures of Magritte’s The Lovers II (1928), and his obsession with hiding and reappearing, but doesn’t force the parallel, and notes that Magritte himself had no interest in exploring his relationship with his deceased mother. Perhaps because of that hard boundary set by Magritte, there is not much discussion of women in political terms in Magritte: A Life, although they appear in Magritte’s life plenty.

This is perhaps the book’s one significant flaw, especially since its best surprises often occur at the intersection of Magritte’s politics and his relationship with other artists. He’s often thought of as quite distinct from the other Surrealists, but Magritte had a solid gang of collaborators, like Paul Nougé and Louis Scutenaire. After World War II, Danchev explains, Magritte was caught forging artworks by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Max Ernst, and himself. These acts of imitation are hyper-symbolic: more Magritte than Magritte, more like Van Gogh’s ear than Van Gogh’s ear.

His painting Le modele rouge is also more like Van

Gogh’s A Pair of Boots than the

original: in Magritte’s version, the battered shoes morph into human feet at

their toes. The worker’s feet aren’t just metaphorically present in Le modele rouge, but literally: Magritte

makes the absent laborer flesh, his toes puncturing the veil of

romanticism

that the Van Goghs of this

world wrap them in.

Doing this kind of political reading of Magritte’s often decorative work, Danchev gives the painter extensive credit for his socialist ideas and resistance to Nazi ideology, before, during and after the occupation of Belgium. He was a member of the Communist Party for a time, and remained committed to the socialist cause until his death. “In a world of Nazi cretins,” as Danchev nicely puts it, “word pictures might be death sentences,” and Magritte took more risks than his own blasé attitude towards his work would ever suggest.

Alex Danchev passed away in 2016, before finishing Magritte: A Life, although, as art historian Sarah Whitfield—author of a number of books, including a Magritte Catalogue Raisonné—explains in her preface, he had written about half of the first sentence of what would have been the final chapter, about the last twenty years of Magritte’s life. It was Danchev’s last book, and it seems appropriate to Magritte’s concern with layering and concealment that the book has been packaged by another writer altogether. Think of the figures from Manet’s original painting, as they exist in this biography: They have been put inside coffins, then inside in a book, which is now inside the edition. They are invisible, and yet their many-layered concealment makes them more rather than less present.

The same is true of Danchev, who never wrote about himself, but revealed himself in his choices of subject. He was born in Bolton, in the north of England. His parents worked in mining and fashion. After studying history and economics at Oxford in the late ‘70s, then training as a teacher, he joined the Royal Army Education Corps and worked there for a decade. He got a PhD in war studies at King’s College London, then took up a lectureship at Keele University in international relations.

At the time of his death, he was professor of the same subject at St Andrews University, and had published biographies of Oliver Franks, Basil Liddell Hart, Georges Braque (the first full biography of the artist), and Paul Cézanne. He was also known as an eloquent critic of the war in Iraq, and published a number of books about philosophical ideas which connect his two fields, modernist art history and modern political science: On Specialness, On Art and War and Terror, and On Good and Evil and the Grey Zone.

Reflecting these varied but surprisingly interlinked interests, and rather like

Magritte himself, Alex Danchev is a great master of the eloquent contradiction.

He calls Magritte’s aesthetic “high-concept and low-toned,” “real but not

realist,” and describes the artist’s reaction to seeing Giorgio de Chirico’s

Surreal masterpieces in 1923 as “an epiphany and a hard slog.” “Charm and

menace combined can reinforce each other,” Danchev writes, describing

Magritte’s interest in Lewis Carroll, and quotes Franz Kafka’s description of his

own works, “puzzles without solutions,” as one applicable to Magritte’s. A pipe

can be not a pipe; your mother’s death is just your mother’s death; margarine

is sometimes margarine and sometimes it isn’t.

Biographies usually attribute weight to moments or eras in a person’s life, building a narrative which will “explain” the artworks, but this one attempts no such thing. “My eyes saw thought,” Magritte once said, about seeing de Chirico’s work for the first time. Magritte: A Life paints scenes, all taken from life, but not forced into the realist mode which can constrain works of this type. “Real but not realist” is Danchev as much as it is his subject.