In the days before Vladimir Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Fox News’s biggest star insisted that the brewing conflict was no big deal. And in a series of monologues done with his trademark condescension, Tucker Carlson insisted that Russia was in the right and Ukraine in the wrong—or, at the very least, there was no discernible moral difference between a flawed democracy and the autocracy poised to invade it.

Despite the stark attention it was receiving from the U.S. government and media, Carlson minimized the matter, characterizing it as a tempest in a teapot, a “border dispute.” Ukraine, in Carlson’s view, was “not a democracy” but rather a client state, “a colony with a puppet regime” that was “essentially managed by the State Department.” For Democrats, moreover, Russia was a tired boogeyman: The party had gone mad with hatred for Putin in response to Russian meddling in the 2016 election. Now that irrational disdain was dangerous and risked tipping the nation into war.

“Democrats want you to hate Putin, anything less is treason,” Carlson said, adding that the party “[did] not need a big and independent country like Russia around” and would stop at nothing to quash it. Carlson’s comments, as many observed, closely tracked with the Kremlin’s own propaganda. They also carried a consistent message. Russia and Vladimir Putin were doing nothing wrong. Ukraine deserved what was coming to it. And if anything, the Democrats were responsible for the rapidly unfolding crisis.

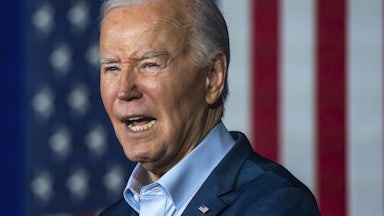

It was a breathtakingly cynical position, but not one that likely surprised anyone with a passing familiarity with Carlson’s Fox News oeuvre. His disdain for democracy is hardly veiled, and his partisanship is similarly barbed. Putin hates Carlson’s enemies: Democrats and the mandarins of the U.S. foreign policy establishment—and thus deserves a pass. Carlson’s job was to make it clear that the unfolding crisis was the fault of Joe Biden and the Democrats, even if it was Putin who was massing troops along the Ukrainian border. The finer points of what was going on didn’t matter. All that did was to ensure that Fox’s viewers were comfortably assured that Biden was to blame.

But it’s all fun and games until the tanks start rolling in and the infernal logic of endorsing a strongman becomes inescapable. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began, Carlson’s tune has changed considerably. Hours after characterizing the issue as a “border dispute,” he was warning his viewers that we were at risk of a “world war.” The fault, moreover, wasn’t that of the United States or Joe Biden or Ukraine. “Vladimir Putin started this war, so whatever the context of the decision that he made, he did it,” Carlson said. “He fired the first shots.” And then he resumed doing Tucker Carlson things: laying the blame at Joe Biden’s feet for being weak and feckless; characterizing himself as some victim. At one point, he played a clip of Democrat Representative Eric Swalwell accusing the Fox host of rooting for Putin. He then told his viewers that he had hesitated to show them such an “awful” video.

What changed? The simplest explanation is that Carlson finally got mugged by reality. For the last five years, he has steadily risen in the ranks of the right-wing media industry by eagerly meeting his viewers where they were: He’s the perfect pundit for the age of negative partisanship, a television host who will stop at nothing to tell his viewers that whatever they happened to be mad at that day is the fault of Democrats. In particular, he has been a font of bogus culture-war stories, devoting long segments to minor controversies about the “cancellation” of Dr. Seuss and the fortitude of female journalists.

But this has also arguably made him overconfident in his ability to contend with matters of serious import, such as foreign affairs. Here, Carlson has struggled to forge something coherent out of the detritus of the so-called “Trump Doctrine.” He has chosen to take the sides of autocrats like Putin and, in particular, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán. He’s shrugged off the value of protecting democracy and condemning tyranny. He has adopted a kind of contemporary Father Coughlin–esque isolationism and dismissed the immoral actions of bad actors. He has little interest in the international order or the rule of law.

In Ukraine, he was likely also making a bet: that either the Biden administration would go too far, enmeshing the United States in yet another costly foreign conflict or, more likely, Putin wouldn’t—that he would settle for a minor incursion into two provinces that were already largely controlled by Russian separatists.

Instead, Vladimir Putin launched a bloody and needless full-scale assault that appears to be on the brink of turning into a long, drawn-out, and extraordinarily costly war. The international community has united against Putin. Far from being weak or feckless, Biden has played a key role in bringing allies together. Despite all the effort Carlson took to boost Putin and defame Ukraine’s democracy, there’s little evidence now that anyone inside or outside of his audience is buying what he’s selling: A CNN poll conducted shortly after the invasion found that 83 percent backed sanctions against Russia. A Reuters/Ipsos poll released on Tuesday found that 71 percent wanted the U.S. to send weapons to Ukraine. Military intervention remains unpopular—42 percent approve, per CNN’s poll. But there is little sympathy among Carlson’s audience. Eighty percent of Republicans think that Biden should be tougher on Russia—the position that Carlson ended up at after arguing the opposite for weeks—per a recent Quinnipiac poll. Carlson judged the situation about as wrongly as one could, underestimating Putin and, crucially, overestimating his own ability to read his audience.

This is a reminder that, for all his influence, Carlson’s stature is ultimately dependent on his ability to shape his viewers’ point of view. He has shown an uncommonly cynical ability to do that—and has done nothing, at any point, to try to push his audience anywhere they might not want to go. But his commentary on the war in Ukraine has proven to be a humiliatingly failed effort in manufacturing consent, one that is enormously satisfying to watch.