The writer Nelson Algren was an American original who, when he died in 1981, left behind a single work of literature that continues to haunt the American imagination. That work is the 1949 novel The Man With the Golden Arm, a book that has come as revelation to a good number of readers in every generation since it was first published. This in itself is a testament to the way a fully realized piece of writing can overcome the limitations of its own genre—in this case, the proletarian novel of the 1930s, which, by the late 1940s, was already in deep disfavor.

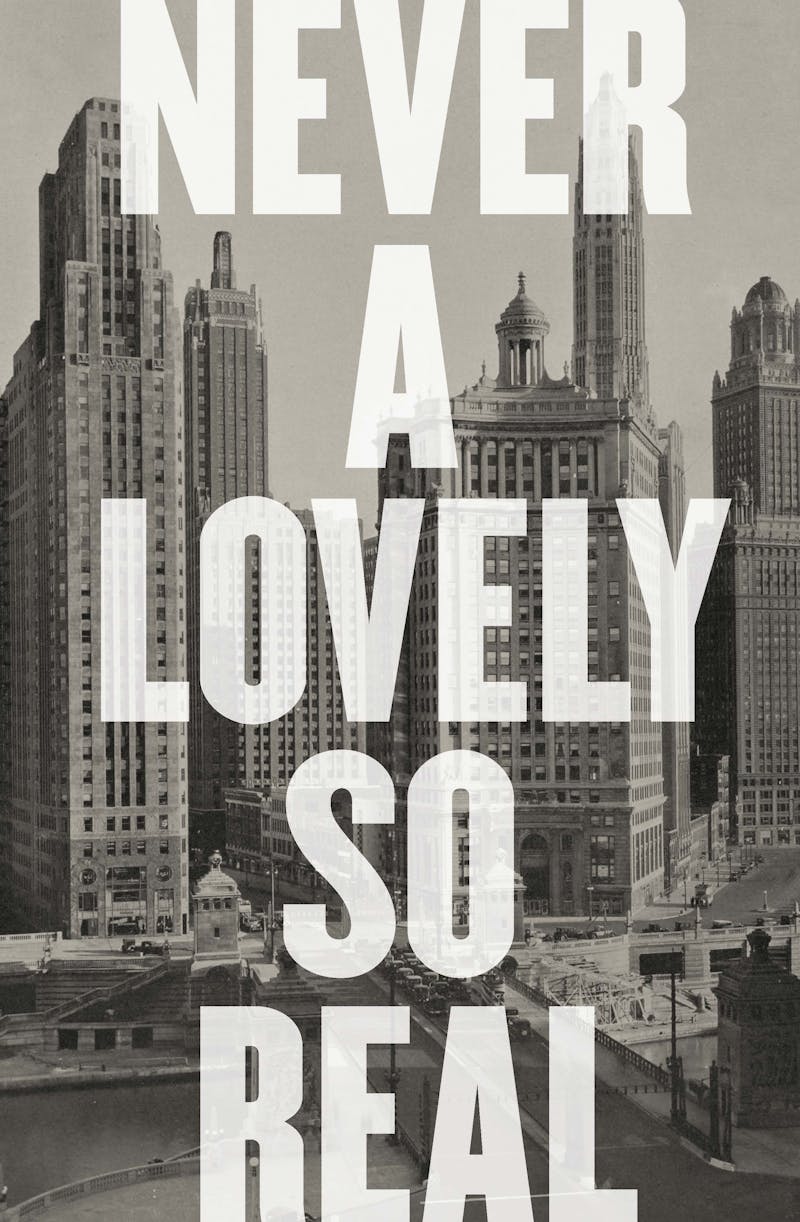

One of the novel’s current devotees is Colin Asher, who has written the newest Algren biography, Never a Lovely So Real. Many of Algren’s biographers were content to write of him as a working-class malcontent stuck in a decades-old style of literary realism. But Asher is a writer of his moment—that is, this moment—and he sees something timely in Algren’s tough-guy devotion to his underclass protagonists: a plea to acknowledge the ruthlessness we regularly deal out to social failure. He wants badly to understand the man for whom this devotion was a central metaphor.

Algren was born in Detroit in 1909 into a Jewish working-class family whose surname was Abraham. When he was three, the family moved to Chicago, where the father worked as a machinist, the mother ran a candy store, and life inside the Abraham household was hell—mainly because Mrs. Abraham was wildly dissatisfied with her life and cried out every day and all day that she hated “her house, her Irish neighbors, her children, and most especially her husband.... She called him a failure in front of their children, she called him stupid.” She yelled, “Get out of my sight!”

The tumult in the house made Nelson withdraw so far into himself that quite early he began to seem emotionally unavailable. In grade school, he’d leave the house in the morning and not return until the light had gone out of the sky. He roamed the streets of Chicago incessantly, which is how he came to love the city. In middle age, Algren wrote that once you’ve fallen in love with Chicago, “You’ll never love another. Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real.”

It was the 1920s, and Chicago was the crime capital of the world. Gangsters were everywhere, operating brothels and speakeasies and gambling clubs in every neighborhood in the city. One of these clubs was right next door to Mr. Abraham’s tire shop. There were cars parked outside the place at all hours of the day and night, with glamorous people coming and going, and dangerous-looking bouncers standing at the club’s entrance. Nelson was mesmerized.

One night in his senior year in high school, he walked into the club alone—and entered a world that would attract him for the rest of his life. Everywhere cards, dice, or roulette were being played; bills of the highest denomination were being flung down on the tables, and everyone was drinking bootleg liquor. Nelson had the feeling that he was in the company of men and women who, win or lose, occupied a different place in the universe than those living outside the club, trapped in the dreariness of everyday respectability. These were “members of a species so high on the food chain, it made its own rules.” If more than half the people in the room were hustlers—cardsharps and racketeers, con artists and drug addicts, hookers and bootleggers—so be it. He walked up to a table and placed a bet. Then he placed another ... and another. Within a few months, Nelson was a club regular. The decision to take his place in this world would prove formative.

No one grows up in an immigrant, working-class neighborhood in any city in America without having some contact with criminality. Either the gangsters own the candy store, or the grocer on the corner is paying protection money, or the local lottery is fixed. Most if not all of the children flirt with low-level lawbreaking, but very few are drawn to making permanent connection with those really living on the other side of the law. Among those few was Nelson Algren. It wasn’t that he sought out the company of drunks, gamblers, and prostitutes for some cheap excitement; it was rather that—deep within himself, in a place he could hardly locate—it seemed to him that these were the only people with whom he could ever identify. Because he was a writer, he at first experienced “his people” sympathetically, then romantically, and at last metaphorically.

The neighborhood that suited Algren best, from the time he was in his twenties, was Polish Downtown, one of the toughest, most crime-ridden sections of the city. A major avenue in Chicago is Division Street, which runs through many neighborhoods. Everyone Algren would ever want to know hung out in the bars and gambling joints that lined the Polish Downtown part of Division Street. Here, Algren lived for some 40 years, mostly alone, in one rat-trap apartment after another, embedded among the people who gave him his raw material. He drank with them, gambled with them, and slept with them; one of them he married twice.

Which leads me to Algren and women. He was always fantasizing that an affair would bring his solitary state to an end; the key word here is fantasizing. He would pursue a woman, often inviting, even begging, her to move in with him, but no sooner had she done so than he began feeling stifled. In no time he’d grow cold, then distant, and finally unreachable. Soon he was sleeping on the couch, and not too long after that he was again living alone.

The only affair that included an attachment of mind and spirit as well as that of the flesh was the one he had with Simone de Beauvoir, who never dreamed of moving in. The French intellectual came to the United States for the first time in the winter of 1947 and, passing through Chicago on her way to California, called Algren. They took a walk, had dinner, and fell into bed where, to their mutual astonishment, a passion flared that made each of them declare themselves in love. Within a few months, Algren asked de Beauvoir to marry him and move to Chicago. She refused, explaining, “The reason I do not stay in Chicago is just this need I [have] to work and give my life a meaning by working.... I should give up [much] to remain forever with you; but I could not live just for happiness and love. I could not give up writing and working in the only place where my writing and work may have a meaning.”

For a year and a half, the connection sustained itself through letters and one or two trans-Atlantic visits, but in the spring of 1949 Algren declared the situation intolerable. “It’s different for you,” he wrote.

You’ve got Sartre and a settled way of life, people, and a vital interest in ideas.... I lead a sterile existence centered exclusively on myself; and I’m not at all happy about it. I’m stuck here, as I told you ... But it leaves me almost no one to talk to ... Last year I would have been afraid of spoiling something by not being faithful to you. Now I know that was foolish, because no arms are warm when they’re on the other side of the ocean ... life is too short and too cold for me to reject all warmth for so many months.

The most important sentence in Algren’s letter is, “But it leaves me almost no one to talk to.” Through de Beauvoir he came close to realizing that the life he could not leave meant a significant part of himself was permanently in exile. He was spending his years among people with whom he could banter but not converse.

It wasn’t just women in the apartment that made Algren feel buried alive. Throughout his life he was repeatedly driven to take off for anywhere-but-here. The first time he bolted, it was 1931, he was 22 years old, and the Great Depression was raging. There were two million people on the road that year, and Nelson seemed to meet and learn from a large number of them. Drifting through Minnesota, Kentucky, Texas, he rode the rails, slept in hobo camps, starved periodically, did jail time, and began to think seriously about the social forces behind this horrifying mass migration that resembled a country at war, with its people fleeing the enemy.

He returned to Chicago a red-hot socialist, and for many of the years ahead Algren would denounce, on the lecture circuit as well as in his work, unregulated capitalism for its cruelty to the people who did not know how to work the system—those, as he put it, “born to be doomed.”

“He had been on his guard since the day he’d been chiseled out of two steel aggies” when he was nine, and now “he felt an almost animal-like yearning to let his guard down and take all the blows there were in the world til there were no blows left: to sink under them in utter weariness into sleep and wake up being the real Frankie Majcinek. The Frankie who was straight with himself as he was with the world. The Frankie he had never been.”

Algren wrote these words about the protagonist of The Man With the Golden Arm, but one way or another he’d been writing them throughout his working life; it was only that with this book they came into brilliant focus.The novel can rightly be called Algren’s masterpiece because in it he made us see and feel, with all the art he was capable of, the world exactly as he saw and felt it: proletarian with an electrifying edge.

The time is 1946 or ’47, the place is the Polish section of Division Street, the characters are men and women who have lived here all their lives, remarkable for surviving in a slum where hardly anyone has finished high school, no one has a job, and everyone makes it by hustling: cards, sex, or drugs. The neighborhood, very much like the neighborhood in Elena Ferrante’s novels, is central to the story being told, in that nobody ever leaves it and nobody ever matures. Here, people simply age in place. Algren gives many of the characters Runyonesque names—Owner, Blind Pig, Record Head—because essentially they are mythical figures on a landscape of foregone conclusions, wearily acting out their assigned roles.

It has always been hard to know if Algren poured himself into Frankie Machine or extracted himself from Frankie, because the relationship between this writer and this character is remarkably dynamic. Either way, the writer’s great accomplishment was to rescue his protagonist from a generic life by inhabiting him so fully and so richly that we, the readers, are utterly absorbed by not only the starkness of Frankie’s situation but the inevitability of its resolution.

Frankie Machine is the man with the golden arm; a remarkably gifted card dealer who works half the night in one of the gambling joints on Division Street. When we meet him, he is a 29-year-old vet who’s come out of the war a drug addict; he is also the husband of Sophie, a childhood sweetheart now confined to a wheelchair because Frankie crashed the car one night while driving drunk. Their marriage, consisting of his guilt and her hatred, seals them into a daily hellishness from which Frankie seeks relief in the arms of Molly-O, a hapless girl who hustles drinks at one of the gambling clubs and occasionally turns a trick.

Frankie dreams of kicking his drug habit and leaving the neighborhood with Molly. Needless to say, he does neither. In fact, he sinks ever deeper into his habit as he struggles to raise the money for a 24-hour fix that is growing more expensive by the day. From the start, he is spiraling down toward a crisis that, by novel’s end, will include robbery, murder, and prison. In the course of which the really unthinkable happens: Frankie loses his magic touch dealing cards. Now time begins to stand still. Emotionally paralyzed, he thinks obsessively of that moment when dealing suddenly began to fail him, and “the light had died in his eyes, leaving only a loneliness that was a loneliness for more than any lost skill.” And what is it he is lonely for? Is he lonely for Molly? Is he lonely for that fantasized new life? No. He’s lonely for a fix. “He was lonely for his old buddy with the thirty five pound monkey on his back.”

The book was a best-selling sensation. Algren’s drive not only to get inside Frankie Machine, but to stay there, took the country by storm. Never before or after would he inhabit a character as dramatically as he did Frankie; nor would the time ever again be as welcoming. Soon enough it was the 1950s, America was deep into the Cold War, and, even though the novel of his life had bestowed wealth and fame on him, Algren found himself on J. Edgar Hoover’s ever-expanding list of potentially dangerous radicals, where, at the very least, everyone, including Algren, was deprived of a passport. He did not leave the country for nearly a decade.

By 1956, when his next novel, A Walk on the Wild Side, appeared, the appetite for his kind of writing had gone to ground. Algren was taken sharply to task for writing a book that Alfred Kazin found saturated in “puerile sentimentality,” Leslie Fiedler declared written by a museum piece, and Norman Podhoretz scorned for trying to tell its middle-class readers that bums and tramps had more humanity than the rest of us. Algren lived on for another 20-odd years, in obscurity and often in need, but a figure of literary legend to those who regularly found The Man With the Golden Arm a book to be cherished if not worshipped.

Never A Lovely So Real is a work of love and prodigious research and, as such, deserves to be honored. Asher has a talent for delivering a great deal of anecdotal information with the kind of relish that feels delicious, and certainly there is much in this biography that any scholar of Nelson Algren’s work will consult with profit.

But in a curious way the book fails to get inside Algren; he never really comes to life in its pages. There are a number of possible reasons for the thinness on this score, but I will speculate on only two. First, there is Asher’s somewhat superficial grasp of the times in which Algren was writing. For instance, he refers to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg as “a married couple who had been convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage.” A married couple! This is the kind of sentence that spells an amateurish distance from the history being described; there are a number of them sprinkled throughout the book, and they are startling to come upon.

Second, there is the hagiographic blandness with which Asher describes the crippling anger from which neither Algren nor his work ever emerged. It flattens both the prose and the analysis. Asher reports that Algren’s final visit to Paris to see de Beauvoir was benign, and long descriptions of their travels together confirm this impression. But according to Deirdre Bair’s scrupulous biography of de Beauvoir, the visit was a disaster, because Algren arrived in a foul mood and spent much of their time together mocking her friends in particular and her life in general. On more than one occasion, I found myself wondering if I could take this or that interpretation of Asher’s on faith.

These caveats aside, I am glad to have read this book and even gladder that it has been published in these most depressing of political times. It serves as an engaging reminder of what a life informed by passionate conviction can look like. Sometime in 1952, Algren delivered a speech at the University of Missouri in which he spoke of the myth of American prosperity, the insanity of McCarthyism, the unending war economy, and the false promise of consumerism, dwelling especially on this last. A “whole houseful of gadgets do not of necessity add up to happiness,” he said, and warned that if your life is defined by “no passions and small cares,” it is not worth living. The underlying message: Do not conform to materialism; aim higher; do better.

To spend time in the presence of someone—whatever his limitations as a man or a writer—who, to the last day of life, remained true not only to an ideal of social justice but to an ideal of the self alive to its own experience—that alone is worth the price of admission to Never a Lovely So Real.