Liberals have never quite known what to make of those who are far to their left. Conservatives tend to conflate liberals and leftists so often that many who fit under the broad Democratic umbrella have fallen into the habit of doing likewise. This is why Democratic operative Peter Daou can write that “Clinton and Sanders supporters … largely have the same goals,” and an NPR reporter can claim that the 2020 Democratic candidates “all basically want to do a lot of the same things.” The difference between liberals and leftists isn’t really a matter of policy, this view goes; the two just differ on tactics and purity and willingness to compromise.

But such a conflation elides actual, significant policy differences and does a disservice to both factions. Liberals—from Nancy Pelosi to Elizabeth Warren—see capitalism as flawed but fundamentally salvageable if managed correctly, with just the right balance of government regulation and free enterprise; leftists—including Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn—see capitalism as definitionally unfair, responsible for much of the world’s misery, and thus “irredeemable,” in the words of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. As the avowed leftist Nathan Robinson put it in an excellent piece from 2017, “Liberals believe that the economic and political system is a machine that has broken down and needs fixing. Leftists believe that the machine is not ‘broken.’ Rather, it is working perfectly well; the problem is that it is a death machine designed to chew up human lives. You don’t fix the death machine, you smash it to bits.”

Perhaps the pièce de résistance of this conflation took place two years ago, when the conservative television personality Piers Morgan invited the activist and writer Ash Sarkar on Good Morning Britain to discuss upcoming protests against Donald Trump in the United Kingdom, protests that she supported and he disdained. Morgan attempted to depict Sarkar as a hypocrite by asking her whether she had also protested Barack Obama—who “deported three million people”—when he visited the U.K. Sarkar answered with an emphatic, “Yes!” but Morgan ignored her, pressing on, at one point exclaiming, “It’s double standards!” When Sarkar calmly encouraged Morgan to “actually check out some of the other work that I’ve done,” he replied that he’d “checked out some basic facts about your hero, Obama.” Shocked, Sarkar shot back, “He’s not my hero—I’m a Communist, you idiot!”

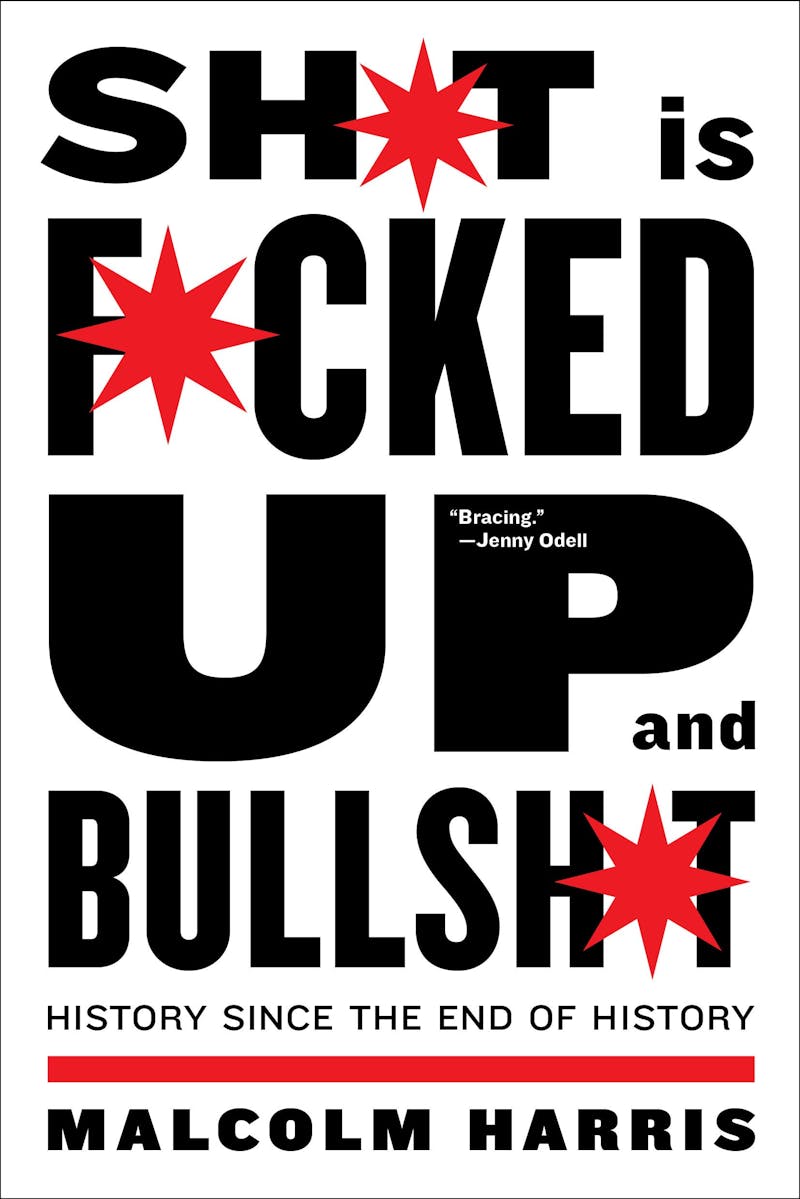

This distinction is important to Shit Is Fucked Up and Bullshit: History Since the End of History, a new book of essays by as outspoken a leftist as Malcolm Harris. While the ideas and the rhetoric Harris espouses are not uncommon in certain corners of the arts, the academy, and the Twitterverse, they are nonetheless rarely articulated so forthrightly and with so few qualms about their consequences. Harris, himself a millennial and the author of Kids These Days—a well-regarded monograph about the conditions under which millennials labor—apparently feels no need to qualify his radicalism with liberal hedging or apologetic backpedaling. His directness and frankness are refreshing—even, occasionally, startling. Taken together, his essays are an indictment, a road map, and a call to action.

Shit Is Fucked Up and Bullshit is a collection of Harris’s writing from the past decade, covering an eclectic range of topics, from Marxism to television to sex with robots. The book begins with Occupy Wall Street and ends with Donald Trump, traveling from a moment of frustration with an unequal status quo to a moment of so much greater frustration with a so much worse status quo. It was at Occupy in 2011 that a man named Micky Smith held up a sign reading, “SHIT IS FUCKED UP AND BULLSHIT,” which became the unlikeliest of rallying cries. What was remarkable about the sign, Harris writes, was that “the whole world knew what he meant.” The whole world still knows what he meant.

Harris himself graduated from college in 2010, a time when the job market was in the gutter and a recent grad had few choices other than to do as Harris did—move back home to California and try to find a job from Craigslist, “a new site focused on the ‘sharing economy.’” He spent a while watching Netflix DVDs, writing on his blog, trying to figure out his next move. He considered graduate school but didn’t get in. Eventually, a cold email to an editor at an online magazine, The New Inquiry, brought him to New York, where he initially stayed in a closet-sized extra bedroom in the editor’s Brooklyn apartment for $400 a month. His writing began to take off, as he placed pieces in n+1, Boston Review, The New Republic, and The New York Times Magazine.

His politics—born, at least in part, from his experiences with precarity—were solidified and electrified with the Occupy movement, which began in August 2011. Several of the book’s first essays chronicle his time in Occupy, including his role in spreading rumors that Radiohead would play for Occupiers in Zuccotti Park, his experience marching with thousands of other Occupiers across the Brooklyn Bridge (and getting arrested for his troubles), and the bizarre legal ramifications that followed. “We didn’t quite get to world revolution,” Harris laments, “but we got a lot further than almost anyone expected.” The symbolism, vocabulary, and urgency of Occupy profoundly impacted American politics, arguably making possible the rise of politicians like Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez. Sometimes, Harris continues, he worries his participation in Occupy will have been “the most important thing I’ll ever do with my life.” Yet in the years that followed, he remained engaged in political work—joining politically oriented volunteer childcare collectives and taking part in anti-fascist protests.

Many of the book’s most remarkable essays emerged from this political activity. In “And Into the Fire: A Letter to the Left”—one of the book’s only heretofore unpublished pieces—Harris critiques the middle-aged, MSNBC-watching, suburban warriors of “The Resistance” and instead makes a passionate case for the efficacy of, well, political violence. True resistance, Harris writes, exists “outside the liberal democratic model envisioned by the American Constitution.” And it is often violent. Not necessarily violent in the sense of assassinations but violent in the sense of toppling statues; defending oneself from white supremacists; or targeting police stations, army barracks, and other symbols of “the racist war machine.” Contrary to many people’s romanticized notions of 1960s protest, this violence was the “resistance” of civil rights activists.

In this one and another essay, “Tactical Lessons From the Civil Rights Movement,” Harris cites the 2015 book, This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible. “Non-violence doesn’t work for everything,” the author, Charles Cobb Jr., told Harris. “You use self-defense with the Klan.” But this becomes more dangerous when the state takes the side of the Klan. Harris reviews the government’s gradual crackdown on left-wing protest, from the formation of the Department of Homeland Security to the enhanced surveillance of environmentalists, Muslim communities, black activists, and Native American water protectors, to mass arrests at the J20 protests on the day of Trump’s inauguration. Respectable resistance is getting harder by the day, even as it’s needed more than ever.

What to do? “Gather a small group of people whom you’d trust with your life and who see the situation the way you do,” he writes. “Meet in person, without your phones, somewhere outside.” Settle on your moral code and prepare to defend yourselves and each other “by whatever means are necessary.” Practice, and be careful. “Being backed into a corner doesn’t leave us with no way out; it leaves us with one: through,” he writes. “Ready or not, see you in the fire.” Agree or disagree, this isn’t the normal fare for a writer whose work appears in places like The New York Times Magazine.

This essay is remarkably provocative, and powerfully written, but one has to wonder how serious Harris truly is. This is the only place in the book where he advocates for this kind of revolutionary violence, other than some vague, fleeting references to “confront[ing] the social infection that is fascism” in the book’s last pages; he devotes far more space, for instance, to delineating various esoteric strains of Marxism. Further, he doesn’t explore at any length what exactly a journey “into the fire” might mean: Are these revolutionary militias purely defensive, or should they be bombing government facilities and munitions plants, as South Africa’s Umkhonto we Sizwe (co-founded by Nelson Mandela) did? Especially since “And Into the Fire” is the book’s first essay following the introduction, it appears that Harris is, at least in part, trying to shock or provoke or freak out his readers right off the bat. It is easier to look back at history and acknowledge that violence has sometimes successfully stopped fascists than it is to affirmatively call on your readers to learn to fight in the woods.

Yet it would be uncharitable to conclude that Harris is simply trying to be provocative for the sake of provocation. As he describes in other essays, he actually has put his own body on the line in anti-fascist protests—and suffered consequences for doing so. If, in trying to articulate what a far-left politics means in the age of Trump, his ideas are occasionally underdeveloped, that seem a fair price to pay for an admirable attempt to reframe all of American politics, to shift the Overton window to include ideas too radical for Bernie Sanders.

Animating Harris’s commitment to such extreme resistance is the profound unfairness of modern America, a subject that consumes much of his book. In one essay, he reviews the CIA’s extensive history of assassinations and calls for writers and filmmakers “to find the bodies, empower the survivors, and tell the big story.” In another, he notes that neoclassical economics does not have a term to explain the growing divergence between labor productivity and wages, but Marxist economics does: the rate of exploitation. “Employers can yell ‘skills gap’ all day long,” he writes, “but they can’t keep workers fooled much longer, and their shareholders are not going to be happy when the only solution left is pitchforks at their doors.”

One of the most unexpectedly powerful essays in the collection is titled, appropriately, “America’s Largest Property Crime.” Shockingly, the largest property crime in the United States, by far, is wage theft. In fact, according to the Economic Policy Institute, wage theft costs American laborers more than $50 billion a year—a phenomenon so extensive, Harris writes, “that it dwarfs the economic cost of every other crime combined, which in 2008 the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated at a mere $17.4 billion.” Yet, as he explains, when bosses refuse to pay, or underpay, their employees, the police don’t handle it; instead, enforcement authority is vested in the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division. This Division is almost comically underfunded compared to its broad mandate, and its investigations rarely result in settlements that make the victims whole. “Employers aren’t wrong to think they can get away with wage theft,” Harris writes, “and many if not most of them do.” With the authorities so hopelessly outmatched—and with wage theft often “the difference between homelessness and shelter, or saving for retirement and a lifetime of subsistence pay”—the only viable solution is to support that last, great bulwark against employer domination: unions.

Perhaps surprisingly, Harris is often at his most insightful in his arts criticism essays. In “Upping the Antihero,” he points out how the classic television antihero—the good cop who is also a rogue cop, a loose cannon dispensing his own idea of justice—“has undergone a neoliberal transformation.” He is now a consultant. From the USA procedurals of Psych, Monk, Burn Notice, and White Collar to the network hits of The Mentalist, Bones, Lie to Me, Numb3rs, and many others, much of the drama has become the precarity of the antihero’s work, as he (or she) searches in vain for steady employment, often existing at the periphery of the government agencies that once provided the antihero with stable employment. In Psych, for instance, a cop’s son cons his way into a job as a police consultant by faking psychic powers; his precarious position means he can care little about the traditional rules of police work, but it also means he’s constantly scrambling for gigs. Perversely, this flexibility ultimately results in him displacing career cops, which “makes sense in an America where the career public servant is no longer the representative worker.”

The essays in Shit Is Fucked Up and Bullshit were written mostly between the summer of 2011 and the fall of 2019, and, at the risk of understating the obvious, the world changed a lot between those two points. Thus, some of the book’s earlier pieces almost have the feel of having been buried in a time capsule. When “Bad Education,” an essay from 2011 decrying government complicity in the mounting student debt crisis, notes in disgust that student loans are “edging ever closer to $1 trillion,” it’s hard to know whether to laugh or to weep. (Today, that number is well over $1.5 trillion.) Nonetheless, Shit Is Fucked Up and Bullshit makes a mostly sustained argument about the profound unfairness of the modern economy and society.

And looking again at the earlier essays, it is astounding to realize how little some things have changed. In the book’s oldest essay, from 2010, “The Loser Wins”—on the Mark Zuckerberg biopic The Social Network—Harris writes that the film “is a conservative story, as is the story of Facebook and Google and every other celebrated firm founded in a humble Northern California garage and offering supposedly leveling technology.” Even as the young tech entrepreneurs disrupt an old hierarchy, “a superseding hierarchy even less equal” takes its place, with those very entrepreneurs right at the top. U.S. Postal Service employees are unionized; are paid good wages; have stability, benefits, and a path to advancement, Harris notes in another essay. But Amazon can deliver more things more quickly. Does that mean we should tolerate the brutal, dystopian conditions it imposes on its employees, or the dynastic wealth hoarding of its founder? We, as a society, will have to decide.

In his classic work of labor history, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression, the scholar Robin D.G. Kelley describes how black workers in Alabama in the 1930s and 1940s collaborated with the Communist Party to fight for economic and racial justice. Few of the sharecroppers and factory workers and domestics Kelley described cared about party politics in Moscow or had ever read Marx. Indeed, it’s unclear how many would even have called themselves Communists. But they were Communists nonetheless, because they recognized that the society in which they struggled and labored was fundamentally unfair, and they wanted something fairer. In a world of rampant exploitation justified by racist oppression, revolutionary change felt rational.

Malcolm Harris is betting that the same thing is true today, that a silent majority might be ready to embrace leftism even if they can’t quote Slavoj Žižek and don’t use words like “dialectic.” Harris writes that 2011 “marked the beginning of the Shit is Fucked Up and Bullshit era,” when it began to be clear that hope and change were only real for the one percent; when a devastating jobs crisis dovetailed with a crushing debt crisis and a housing crisis and the rise of panoptic new technologies and grinning, neofascist politicians. “If the title of this book speaks to a phenomenon you already recognize intuitively, then I hope the contents help clarify how and why, and maybe even point to a way for things to be otherwise,” Harris writes. “And if the title doesn’t make sense to you yet? It will.”