Dissident is an unpaid position, Steve Naman told me this fall. The 77-year-old resident of suburban Atlanta is the longtime president (and accountant, webmaster, and proofreader) of the American Council for Judaism—for decades the lonely standard-bearer of the Reform movement’s beleaguered anti-Zionist wing. In its heyday, the group boasted as many as 20,000 members, and its combative director, Rabbi Elmer Berger, was a reliable thorn in the side of the Zionist establishment. Berger was a devoted advocate of American Jewish assimilation—a fulfillment, in his view, of the universalism espoused by the Hebrew prophets. Perhaps more important, he was a fierce opponent of Jewish nationalism, which he considered an invitation to catastrophe.

“Regrettably, all the predictions that the council made have pretty much come true,” added Naman, a retired paper company executive, who also volunteers for his daughter’s hunger nonprofit, Bagel Rescue. Several weeks before, Palestinian militants had mounted a surprise assault on Israeli communities and military installations near the Gaza border, slaying some 1,200 Israelis, most of them civilians. Though negotiations were ongoing, around 240 hostages were still held by Hamas. Northern Gaza was under heavy Israeli bombardment. An estimated 10,000 Palestinians had been slaughtered, the majority civilians, and 100,000 displaced, numbers that have multiplied considerably since then. Naman pointed to the Palestinians’ plight over the past 75 years. “What did people think was going to happen?” he said. “They were just gonna say, ‘Oh, yeah, put us in a ghetto, and we’ll just live here in poverty for the rest of our lives’?”

If anti-Zionist Judaism has long sounded like an oxymoron, chalk it up to two factors: the Shoah, which convinced many Jews that they could never again entrust their welfare to a non-Jewish majority; and a remarkably effective effort by the Zionist establishment to weave the nation-state project into the fabric of Jewish life. But things change: A few days after October 7, I was biking along Brooklyn’s Prospect Park when I came upon a demonstration in front of Senator Chuck Schumer’s apartment building. I’d spent the week absorbed in the news, struggling to take in the immensity and cruelty of the Hamas attack and horrified by the ruthlessness of Israel’s military response. As demonstrators, many carrying signs reading NOT IN MY NAME, marched down the road to Grand Army Plaza, I noticed that some were wearing tallitot and yarmulkes, and I found myself overcome with emotion. This, the first post–October 7 protest by Jewish Voice for Peace—a group I had never even heard of—struck me as a welcome response to what we’d been seeing, and a deeply Jewish one. I ditched my bike and joined the throng.

I mention this in the spirit of full disclosure: I’m hardly an objective observer. I’m a secular Jew, with my own particular set of feelings about Israel—a confusing mix of esteem, curiosity, anguish, and sometimes shame. I have never before considered myself anti-Zionist. But lately, viewing the images of lifeless children, listening to the dehumanizing rhetoric of Israeli politicians and soldiers, and noting the censorious response of the American Zionist establishment to pro-Palestinian advocacy, I’m not quite sure.

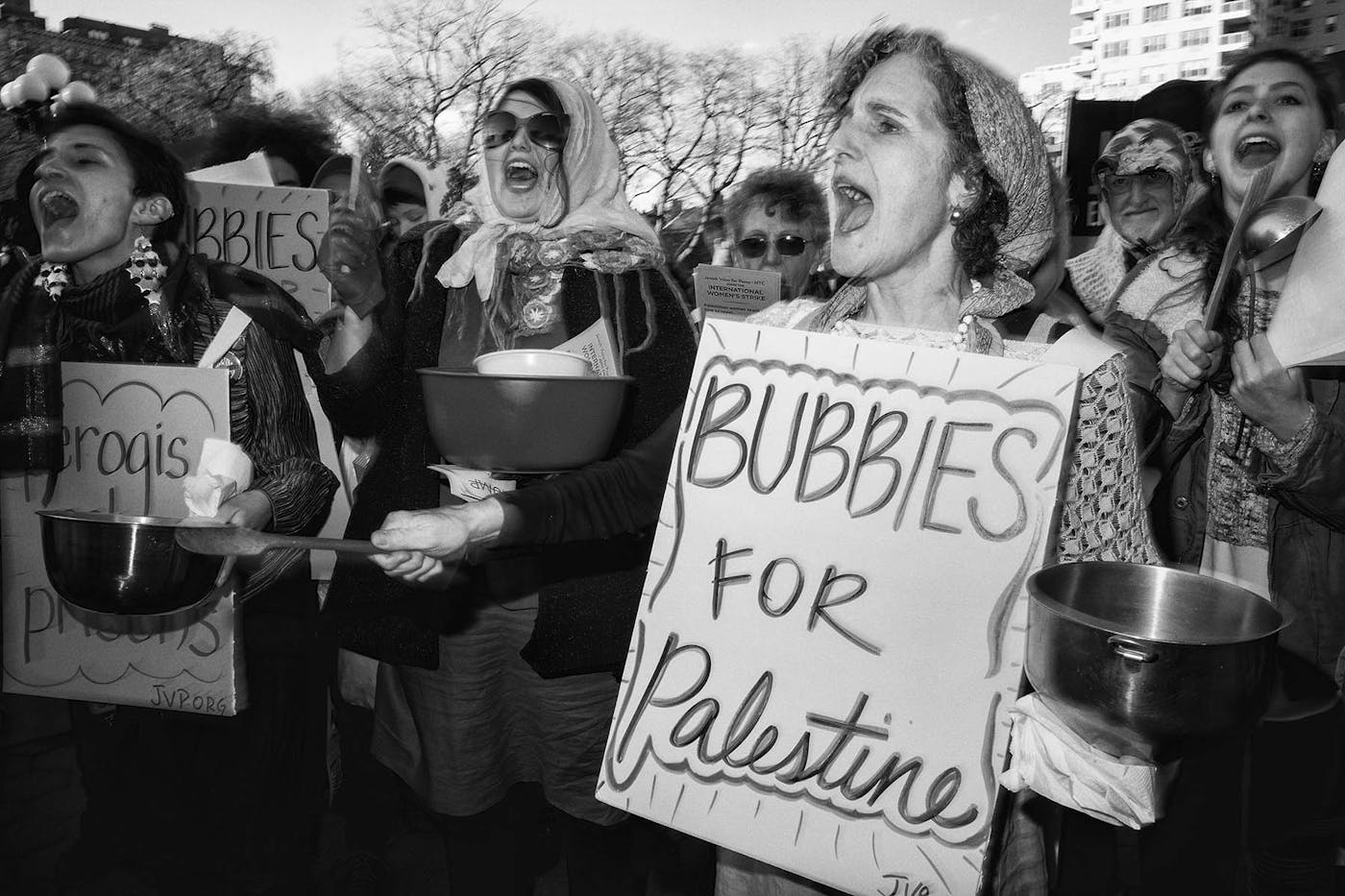

For years, Naman told me, Rabbi Berger was vilified for his anti-Zionist stance; eventually, he was ignored. ACJ membership nose-dived following Israel’s triumph in 1967’s Six-Day War. Suddenly, however, Naman has company. Young American Jews are showing a newfound willingness to publicly question—and sometimes to loudly condemn—the very idea of a Jewish state. Groups like Jewish Voice for Peace and IfNotNow have been at the forefront of some of the most effective anti-war demonstrations we’ve seen in decades. (The tableau of hundreds of Jews in black T-shirts occupying Grand Central Station is particularly indelible.) They’re still far from a majority, of course. “It’s basically noise,” a PR executive at a newly launched pro-Israel PR shop insisted. Gil Troy, a professor of North American history at McGill University and the author of The Zionist Ideas, agreed. “I just say, as a historian, put it in proportion,” he suggested, comparing the reported 290,000 people who attended the March for Israel rally on the National Mall in November with the 150-strong demonstration organized by JVP and IfNotNow the following night outside Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington, D.C.

For Derek Penslar, director of Harvard’s Center for Jewish Studies and author of Zionism: An Emotional State, it’s not about numbers. “These young people do matter,” he said, adding that the Jews most critical of Israel are concentrated in elite institutions, like the Ivies. “They tend to be privileged and very bright and successful, and they will go on to have positions of power and visibility. And so, you know, there’ll be quite a multiplier effect of their views.”

This small contingent has already served as a powerful rejoinder to the notion that, as Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan Greenblatt put it recently, “anti-Zionism is antisemitism. Full stop.” His comments calling pro-Palestinian advocacy groups like Students for Justice in Palestine and JVP the “photo inverse of the extreme right” drew sharp criticism, not least from his own staff. If Greenblatt’s fierce response betrayed a hint of panic, it’s not hard to see why: This incipient movement has already loosened the Israel lobby’s famous grip on the political establishment. (Note, for example, the House Democratic leadership’s defiance of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC, in endorsing incumbent progressive Summer Lee of Pennsylvania.)

Some 75 years since Israel’s founding, the Zionist consensus, what Oberlin Jewish studies professor Matthew Berkman has wryly described as the era of “two Jews, one opinion,” is dead. Even before the current round of hostilities, a survey found that fully a quarter of Jews in the United States considered Israel an “apartheid state,” and 22 percent believed the country was committing genocide. “I think American Jewry is kind of broken, it’s generationally fractured,” Shaul Magid, distinguished fellow of Jewish studies at Dartmouth College and author of The Necessity of Exile, told me. The change isn’t limited to American Jews. Last March, a poll found for the first time that U.S. Democrats as a whole were more sympathetic to Palestinians than Israelis. (The margin was 49 percent to 38 percent.) For Rashid Khalidi, professor of modern Arab studies at Columbia and author of The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, the shift reflects a “thirst for justice among young people.” Israel, Khalidi pointed out, is a prosperous, white-dominated country: “They think of it as they think of the United States in terms of injustice and in terms of inequality.” As former Anti-Defamation League director Abe Foxman put it in the hotly contested 2023 documentary

Israelism, “When we talk about ‘We’re losing the kids’—we lost them!”

A number of pro-Israel commentators have sought to blame TikTok—a dubious charge (OK boomer) that nonetheless contains a grain of truth. Seemingly blindsided by the waning authority of traditional news sources, Zionist advocacy groups that once displayed a formidable knack for shaping public opinion are plainly losing the digital battle for hearts and minds. “For all of the criticisms from the right of … the mainstream media, I think they have been an enormously important pillar of a largely Israeli narrative over the years, and younger people are much less likely to pay any attention” to them, Khalidi said. “Many students I know watch livestreams from Gaza, from people they know and have come to trust.”

Ironically, Israel may have become a victim of its longtime messaging prowess: Even as treasured hasbara chestnuts (“The most moral army in the world,” “No partner for peace,” “They never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity,” etc.) have grown stale, the suppression of the Palestinian narrative has given its sudden emergence via alternative channels a revelatory force.

As the conflict has gone on, other aspects of the Zionist story have come under increased scrutiny. Anti-Zionists can cite the diary of Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, outlining his plan to “spirit the penniless population across the border.” Or that of Yosef Weitz, a leader of the Jewish National Fund, who argued, “The only solution is a Land of Israel devoid of Arabs. There is no room here for compromise.” They can parse the language of the Balfour Declaration, the 1917 letter that led to the establishment of Israel, including its pointed defense of “the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.” They can read the prescient warnings by Hebrew University founder Judah Magnes, Albert Einstein, and others. They can dig into the revelations of Israeli “New Historians” like Benny Morris and Ilan Pappé, which exposed the less palatable aspects of the nation’s founding. And they can encounter anti-Zionist Haredi sects like the Satmars and Neturei Karta, and watch unfiltered interviews with Peter Beinart, Noam Chomsky, and Norman Finkelstein.

Israel’s inexorable rightward lurch over the past two decades has further tarnished the Zionist brand. While supporters are fond of pointing out that the country is the only democracy in the Middle East, it’s not a secret that the long-standing primacy of the left-wing Labor Party ended with a political assassination, nor that the vitriolic atmosphere in which the killing took place was created, in part, by the man who would win the next election. Benjamin Netanyahu went on to become the dominant figure in Israeli politics, with dire consequences. Even while battling corruption allegations, he pushed the adoption of the 2018 nation-state law, which declared citizens’ “right to exercise national self-determination” to be “unique to the Jewish people.” He crusaded for a controversial “judicial reform” law that many observers liken to a political coup. He threw the nation’s support behind Donald Trump along with nationalists like Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and Poland’s Andrzej Duda. And he ushered reprehensible characters like Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich into the political mainstream. Meanwhile, the lobby group AIPAC has charted a similar path to the right, alienating liberals by supporting more than 100 Republican candidates despite their votes to overturn Joe Biden’s election. Given the political inclinations of American Jews, who vote Democratic by greater than a two-to-one margin, a rupture was probably inevitable.

It certainly seemed so on a Philadelphia highway overpass in December, where several hundred JVP protesters celebrated the eighth night of Hanukkah by blocking traffic. Having abandoned the idea of erecting a nine-foot menorah in the road, due to an overwhelming police presence, the group made do with a small wooden toy instead. According to the Talmud, the menorah should be lit at a time and place where the most people can “benefit from the light,” a member of Rabbis4Ceasefire explained via bullhorn, “and so we offer gratitude to the helicopters above who are helpfully participating in this ritual” and “spreading our call for the miracles of a cease-fire now.” A cheer went up. Watching as another rabbi led the group in song, I recognized the lyrics from Hebrew school: “Lo yisa goy el goy cherev.” It’s from Isaiah 2:4: “Nation shall not lift sword against nation.” Meanwhile, below us on I-76, all three lanes of westbound rush-hour traffic came to a standstill as another contingent of activists ran onto the roadway and locked arms.

Dusk brought a pinkish hue to the stone walls of the nearby Philadelphia Museum of Art, and I recalled something Steve Naman had said. After decades in the wilderness, ACJ’s message finally seemed to be breaking through. Maybe the council’s role had been to part the waters, he suggested, so that other Jews could follow.

Upward of 40 years ago, I was a chanich, a camper, at Moshava, a sleepaway camp. Mosh was the mid-Atlantic outpost of Habonim (now Habonim Dror), a progressive Jewish youth movement devoted to creating, as its website states, “a personal bond and commitment” to Israel. If my own biggest takeaway from the experience was a fondness for cigarettes that bedevils me to this day, that’s hardly the organization’s fault. The older kids who turned me on to “smoking cloves” were probably no more aware than I was that their colorful packets of Indonesian imports, sweet-tasting and filterless, were mostly tobacco.

Habonim, which means “the builders,” was established in the United Kingdom in 1929 in an effort to spread the doctrine of Labor Zionism, an uneasy synthesis of two strains of nineteenth-century European Jewish thought: socialism and Jewish nationalism. The former, although rarely referred to directly, was central to the camp’s design. Campers gardened and took care of chickens; they mopped the mess hall, served the meals, washed the dishes, and scrubbed the toilets. I signed on for garbage duty, a taste of collective labor that soon, however perversely, became a favorite activity.

Meanwhile, camp sought to inculcate the spirit of Zionism. Mornings began with the singing of “Hatikva,” the Israeli national anthem; hours of Israeli dancing followed Shabbat dinners. And then there was Aliyah Bet. A long-standing camp tradition, it took place late one night a few weeks into the session. I remember being wakened by instructions shouted in Hebrew, flopping groggily from my sleeping bag, and being hustled out into the humid night. “Sheket,” we were told. “Be quiet.” The woods were dark. Only the counselors, gruffly playacting as Jewish paramilitaries, had flashlights. At some point, I was hoisted into a tree fork and instructed to jump down to the grass. I doubt it was more than three or four feet, but in the dark, exhausted, I hesitated. “Go, go, go!” someone whispered, and I complied, rising unharmed and giddy. Eventually we made our way to the dock, climbed into canoes, and were piloted around the silent lake before arriving back at shore. After cups of hot chocolate, we slipped into bed, hearts racing.

As exhilarating as the exercise was, I didn’t pick up on its larger significance. It was only as I began thinking about this story that I reflected on what the experience had been designed to teach me. For all its left-leaning ideals, Mosh was and still is part of a sprawling and well-financed ecosystem of committees, federations, lobbying groups, educational nonprofits, and other entities that work together to nurture Jewish culture and promote Zionist politics. Aliyah Bet was the code name that the Haganah militants used for their yearslong effort to spirit European Jewish refugees past a British naval blockade and into Mandatory Palestine. What I remembered merely as a hazy nighttime escapade had been intended as a living history lesson: a simulation of the Jewish settlement of the Promised Land.

At a moment when many liberal Jews find their emotional attachment to the Jewish state challenged as never before, when the word “Zionism” is as liable to conjure images of ruined Gaza neighborhoods and broken young bodies as of plucky Jewish kibbutzniks in bucket hats, that night in the woods has taken on a haunting metaphorical significance for me. I think of the drowsy American kids excitedly restaging one of the most heavily romanticized episodes in Jewish history, unwitting conscripts in a geopolitical power struggle. I think of the so-called Arab Question, conspicuously unasked. And I think of the crisp reflection of the moon on the lake, of the paddles thumping the boat’s hull as they stirred the glassy surface, and of the depths beneath.

It makes sense that of all the chapters of Israeli history, this was the one selected for reenactment, and not only because some American members of Habonim had actually served as crew on Aliyah Bet transport ships. It’s an uplifting adventure story, in which a downtrodden and terrorized population emerges from its intended annihilation, cleverly outsmarts its adversaries, and embarks on the grueling but estimable undertaking of building a new nation. That the bad guys in this tale are the British, unambiguously an imperial power, offers the bonus of framing Israel’s founding as one of the century’s great anti-colonial triumphs. Meanwhile, the Mediterranean voyage symbolized an almost mystical renewal, when Jews transformed themselves from passive victims, meekly submitting to their own extermination, into a ruddy new race of pioneer-warriors, at last standing unbowed among the free peoples of the world. And conveniently, it’s a soothing ideological fairy tale in which Palestinian Arabs—some 300,000 of whom had been expelled even before May 1948, with 450,000 soon to follow—play no role whatsoever.

This stirring redemption story, which became the basis for not only a summer-camp romp but a succession of Hollywood movies—including the epic Sword in the Desert (released in 1949, while the ink was still drying on Israel’s Declaration of Independence); the Kirk Douglas psychodrama The Juggler (1953); and 1960’s Paul Newman blockbuster Exodus, based on Leon Uris’s bestselling novel—owes its broad outlines in part to the reporting of I.F. Stone. In 1946, the radical Jewish American journalist embedded with a group of Jewish “displaced persons” from Poland as they traversed war-torn Europe, boarded a decommissioned Canadian naval ship in Italy, and made their way to Palestine. Originally published in the newspaper PM, Stone’s dispatches were collected in the 1946 book Underground to Palestine, in which the author states plainly, “I did not go to join them ... as a newspaperman merely in search of a good story, but as a kinsman, fulfilling a moral obligation to my brothers.” Stone favored the establishment of a binational Arab-Jewish state, noting that Jews and Arabs coexisted peacefully in the city of Haifa and that “there is no such ill feeling in Palestine between Jew and Arab as exists in Czechoslovakia between Czech and Slovak.” Martin Buber, Hannah Arendt, and many others agreed. The elusive “two-state solution” nonetheless became the prevailing diplomatic objective for decades, and it remains so for the Biden administration and many liberal Jews, despite its waning popularity among Israelis.

Reservations about defining Israel as a Jewish state were largely forgotten as the fledgling nation pulled off a succession of victories. Assailed from all sides as the last British troops left Haifa, the newly minted armed forces vanquished five adversaries. The nation established a democratic system; corralled a disparate, polyglot, trauma-stricken population into a single society with a common language; farmed and cultivated areas that had been fallow—and many others that had not—and gradually built one of the world’s most successful economies. (Meanwhile, it brought the world drip irrigation, Waze, Mastermind, and the Epilady hair-removal system, among other innovations.)

To many onlookers, and not only Jews, such developments seemed altogether miraculous. By the time Saul Bellow visited Israel in 1975, the Jewish novelist who’d opened his Adventures of Augie March with the bold assimilationist avowal, “I am an American, Chicago born,” was practically swooning for the ancient motherland, where “the stunned remnant that had crept from Auschwitz had demonstrated that they could farm a barren land, industrialize it, build cities, make a society, do research, philosophize, write books, sustain a great moral tradition, and, finally, create an army of tough fighters.”

One can grant, certainly, that the Israeli story—or rather part of it—was indeed a tale of enormous triumph over unimaginable adversity. In his 1979 book, The Question of Palestine, no less an advocate of Palestinian self-determination than Edward Said readily acknowledged “the intertwined terror and the exultation out of which Zionism has been nourished,” going on to allow that the country “has some remarkable political and cultural achievements to its credit, quite apart from its spectacular military successes.”

The fact that these successes were as braided as a challah with the subjugation, dispossession, and violent abuse of Said’s compatriots—a people with its own aspirations, tragedies, human rights, flawed politics, and undeniable connection to the same land—was for Bellow and many others an unfortunate footnote at best. While this elision can mostly be attributed to a deliberate program of political propaganda and Western anti-Arab sentiment, Jewish exceptionalism no doubt played a role. By virtue of our reputed “chosen-ness,” the Jews have been at once sanctified and stricken with the most acute case of main-character syndrome in world history. Our victimhood is ordained. So is our exile and redemption. It’s all part of a grand narrative that for many of the world’s billions of Jews, Christians, and Muslims is a matter of religious faith. Perhaps that helps explain why a secular American Jew like me is writing this story about the questionable legacy of Zionism, rather than one of the countless Palestinians who have suffered its effects. For better or worse, Jews remain at the center of the story; as such, we’re the ones busy rewriting it.

I.F. Stone began doing so as far back as 1967. Even as Jews around the world were giddy with millennial zeal after Israel seized East Jerusalem and the West Bank, the iconoclastic journalist was tartly observing in The New York Review of Books that “those caught up in Prophetic fervor soon begin to feel that the light they hoped to see out of Zion is only that of another narrow nationalism.” Jewish treatment of Palestinians, he adjudged, “will determine what kind of people we become: either oppressors and racists in our turn like those from whom we have suffered, or a nobler race able to transcend the tribal xenophobias that afflict mankind.”

It turns out all the original Zionists were Christians. As early as the seventeenth century, Puritans and Calvinists seized on the idea of reestablishing Jews in Palestine as a necessary precursor to the Messiah’s return. Champions of the concept included the prominent Massachusetts Bay Colony minister John Cotton and Sir Isaac Newton.

While “proto-Zionism,” as it is now known, made little practical headway, its influence in the United Kingdom helped pave the way for that country’s eventual promotion of the Zionist project, just as American evangelicals are among Israel’s greatest boosters today. It was under the sway of this eschatology that English nobleman Lord Shaftesbury in 1853 wrote a letter to the British prime minister. Employing a construction that would be repeated for decades to come—to the justifiable outrage of the Palestinian people—he insisted that the Holy Land was “a country without a nation” in need of “a nation without a country.” As it so happened, Shaftesbury added, there was just such a nation awaiting its divinely ordained restoration: “the ancient and rightful lords of the soil, the Jews!”

These “rightful lords” needed some convincing, however. Their reluctance took a variety of forms. Most considered the idea wildly fanciful. Indeed, it would take the demise of three empires, two world wars, and a genocide to make the plan even vaguely workable. Jewish communists and socialists opposed nationalism of all kinds as a bourgeois plot to divide the working class. And Orthodox spiritual leaders objected that only divine providence could bring about redemption, and that Zionism was therefore a sin against God that would lead to ruin. It didn’t help that many of Zionism’s early proponents were atheists. Finally, even in an era when colonialism was viewed, at least in Europe, as an unalloyed good, there were those who objected to the notion of creating a Jewish nation on Arab-populated land. The Russian Jewish writer Ahad Ha’am began visiting Palestine in 1891 and spent years writing reports critical of the settlement project. Decrying a widespread belief that “the only language that the Arabs understand is that of force” (a time-tested rationale for violence routinely employed by both sides of the current conflict), he accused the Jewish colonists of treating “the Arabs with hostility and cruelty,” attributing the behavior to resentment “towards those who reminded them that there is still another people in the land of Israel that have been living there and does not intend to leave.” Nonetheless, Ahad Ha’am, the forefather of so-called Cultural Zionism, which promoted a linguistic and cultural Jewish renaissance with Palestine at its center but downplayed the necessity of an exclusively Jewish nation, eventually emigrated to Palestine himself.

By contrast, writer, politician, and militant Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the founder of so-called Revisionist Zionism, advocated a hard line toward the Arabs. Unlike other Zionist leaders, who kept their goal of creating a Jewish majority largely under wraps (Theodor Herzl wrote in his diary of doing so “discreetly and circumspectly”), Jabotinsky said the quiet part out loud: Palestinians were a people; they were a majority in the land that would become Israel, and they wouldn’t yield—why would they?—unless forced to do so. “There is only one thing the Zionists want, and it is that one thing that the Arabs do not want,” he wrote in his famous essay “The Iron Wall.” To create a Jewish state, he said bluntly, would necessitate turning the Arabs into a minority—“and a minority status is not a good thing, as the Jews themselves are never tired of pointing out.” Jabotinsky’s prescription was simple: Exercise power without apology, and wait them out. Naturally, the Palestinians will relent only when there is “no longer any hope of getting rid of us, because they can make no breach in the iron wall,” he explained. (Interestingly, the Iron Wall was also the nickname given to the billion-dollar border fence with which Israel encircled Gaza—the one unceremoniously felled by Hamas bulldozers on October 7.)

Cold-blooded though it may sound today, Jabotinsky’s philosophy was a reasonable response to his own hard experience with antisemitism: As pogroms swept Russia, he established militias devoted to Jewish self-defense. Foreseeing a looming disaster for the Jews of Europe as early as 1936, he devised an elaborate evacuation plan. Though he clashed with Israel’s founders David Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann, his conviction that the only guarantor of survival was power—a view soon validated by the Holocaust—became tremendously influential, and in time the Revisionists evolved into the Likud Party.

Rashid Khalidi views Jabotinsky as “the only honest one” of the early Zionists. His mistake, Khalidi said, was that he “assumed that he was operating in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, when you could get away with this stuff, an era when colonialism was seen as a good thing.” Native Americans certainly fought back, as did other aboriginal groups, “but they were crushed,” he added. “That didn’t work in the twentieth century. Libya didn’t work. Algeria didn’t work. Kenya didn’t work. South Africa didn’t work.”

Meanwhile, there’s a powerful irony here that is often overlooked: Palestinian national identity owes no small part of its vitality and resilience to the decades of collective suffering that Zionism has imposed. Palestinians have “experienced a trauma that other Arab peoples haven’t,” Khalidi pointed out. “And if anybody should be able to understand that, it’s Jews, who suffered repeated bouts of persecution and trauma over centuries, which bind them together, obviously.”

An interesting quality of Jabotinsky’s dispassionate realpolitik is that it’s so fundamentally apolitical—indeed, one can scarcely read his follow-up essay, “The Ethics of the Iron Wall,” without seeing in it an endorsement of the Palestinian, rather than the Israeli, cause. “The principle of self-determination does not mean that if someone has seized a stretch of land it must remain in his possession for all time,” he wrote, “and that he who was forcibly ejected from his land must always remain homeless.”

On October 11, as the Israeli military ramped up its counterattack on Gaza, a box truck circled Harvard’s campus, its exterior walls covered with digital screens displaying students belonging to groups that opposed the war; these it termed HARVARD’S LEADING ANTISEMITES. The “doxing truck,” which was sponsored by the right-wing Accuracy in Media and later turned up at Yale and other institutions, signaled a troubling new stage in the effort of Zionist advocacy groups to smother, rather than engage with, debate about the conflict. To Derek Penslar, a Zionist who has lived and taught in Israel and suffers from what he jokingly calls “Israel attachment disorder,” these attempts at intimidation and repression—including the long-standing ban by college campus organization Hillel International on any speakers at its events who support the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement—are a mistake. “I think we are actually harming ourselves,” he said, “by not allowing a wide range of viewpoints” to be expressed.

That’s not to say advocates aren’t keeping busy. They seem to direct most of their efforts to those who are already onboard, however, providing palliative talking points to an older generation—fervent supporters with money to donate—that rarely pushes back. This represents not only “an intellectual failure,” Penslar said, but also “a tactical mistake”: “Using the language from the 1970s or ’80s to try to motivate young Jews in the 2020s is simply not going to work.” Such organizations “are unelected” and “responsible to no one,” Penslar added. “They speak for no one but themselves.”

A few weeks after we spoke, Penslar himself became the unlikely subject of a cancellation campaign. After being tapped to co-chair Harvard’s presidential task force on antisemitism (an initiative that began after the ugly takedown of the university’s former president, Claudine Gay), Penslar was denounced by a number of high-profile Israel supporters, including the economist Lawrence Summers, Republican Representative Elise Stefanik, and hedge-funder-turned-plagiarism expert Bill Ackman. More than 200 Jewish studies professors promptly issued an open letter of support, and Penslar’s new assignment seems safe for now.

In reporting this story, I reached out to a variety of mainstream Zionist organizations, including AIPAC and the ADL, for interviews. Despite maintaining well-financed communications teams, most didn’t bother to reply. Two asked to speak off the record.

That’s not to say there aren’t still partisans who are willing to make the case. On a late afternoon in January, I paid a visit to Ruth Wisse, professor emerita of Yiddish literature at Harvard, columnist for Commentary, and author of the 2021 memoir, Free as a Jew. Wisse received me in her tidy apartment on the Upper East Side. Wry and grandmotherly, she wore a cardigan and a sling on her arm, a consequence of recent carpal tunnel surgery. She immediately offered me a drink. I had bourbon (“Like my kids,” she said); Wisse sipped vodka.

Earlier that day, South Africa had delivered its genocide case against Israel at the United Nation’s International Court of Justice, and I wondered if Wisse had watched the hearing. She wasn’t interested. The United Nations “had already become the leading forum for antisemitism when it passed Resolution 3379 calling Zionism—the reclamation of Jewish sovereignty—a form of racism,” she explained. “Its court has no legitimacy. The United Nations charter grants all nations equal rights, irrespective of their size. How dare Arab countries remain members of the United Nations if they did not accept the legitimacy of another member state?”

Israel’s mistake, she offered, was to appear in court at all. “Jews are always being accused,” she said. “You should never step into the defendant’s box voluntarily in a trial that is rigged.”

At age four, in 1940, Wisse fled Romania with her family, boarding the last passenger ship to cross the Atlantic, she told me. Antisemitism is not an abstract concept for her. The family settled in Montreal, but her mother regularly warned her not to let her guard down. Life is a war, she’d tell her. Wisse has been fighting it, without apology, ever since. “Do you know how much restraint it has taken over these thousands of years to create a Jewish people, and to keep it alive?” she asked. “‘Don’t step out of line, because you’ll trigger collective punishment against us.’ But now we’re no longer a diaspora people. We have a nation to defend, a national homeland. We have to change our thinking of 2,000 years and to stand up for Israel’s rights, wherever we live, and expect all good people to join us.”

While resistance to Zionism might have seemed reasonable in the 1920s or 1930s, she said, “the creation of the state changes the entire picture, because now to be anti-Zionist is a genocidal concept. If you’re an anti-Zionist, you’re against the existence of Israel, which is no longer a movement of self-liberation but the realized homeland of nine million people, Jews and their fellow citizens.”

Wisse wasn’t surprised to hear of young Jews adopting anti-Zionist ideas. “It is always tempting to blame the Jews for the aggression against them,” she pointed out. “‘Oh, if only Israel didn’t “occupy” the West Bank, then they wouldn’t be against the Jews.’ Many Jews buy into that…. German Jews famously said, ‘If only we shaved our beards, if we started speaking German.’”

Wisse’s defiant tone is noteworthy—“There’s a war on, my friend,” she told me when I gently pushed back on one point—but her views are far from unique. The author Joshua Cohen won the Pulitzer Prize for his 2021 novel, The Netanyahus, a savage takedown of young Bibi and his family. Cohen, who holds Israeli citizenship and speaks Hebrew fluently, considers the current prime minister a disaster. “Everyone I know in Israel rejects Netanyahu and would strangle him on the street if they could,” he told me. “And yet they’re also Zionists who believe Israel should exist and should thrive. There’s a vast middle ground between condemning Netanyahu to history’s judgment and condemning the state he governs to destruction.”

Cohen thinks most countries would react as Israel has to the October 7 attack, and that Hamas’s savagery has been unfairly excused by the left. “America uses Israel, and I’d even say uses Jews, to fight its own proxy wars about race and privilege,” he argued. Bellow had made a similar observation: “What Switzerland is to winter holidays and the Dalmatian coast to summer tourists,” he wrote, “Israel and the Palestinians are to the West’s need for justice—a sort of moral resort area.”

As for the protesters in JVP and similar groups, Cohen was sharply dismissive. “Most anti-Zionists are not going to be Jews in a generation,” he predicted. “The vast majority of these Jews don’t speak any of the Jewish languages. They don’t know the Jewish texts or live in Israel. And if they’re going to have children, there’s nearly a 50 percent chance they’re not going to have them with Jews or raise them as Jews. For these Jews to oppose Zionism, for these Jews to have reserved for themselves as the final expression of their Jewishness the condemnation of Israel—I have to salute them, I might even bow down to them. That’s ultimate chutzpah.”

Anti-Zionist Jews are regularly subjected to personal attacks like this. They’re accused of sucking up to the goyim, of being naïve and ill-informed, self-hating apologists or radical chic wannabes. Gil Troy, the McGill historian, suggested that members of IfNotNow, whose protests often include Jewish symbols and rituals, have an “almost Maoist genius for understanding what’s going to drive their parents crazy.” Responding to an IfNotNow announcement of a cease-fire rally at the White House, David Friedman, Trump’s ambassador to Israel, declared: “Any American Jew attending this rally is not a Jew—yes I said it!”

Cohen’s point was a shade subtler. Frankly, I doubt it was true for a lot of the members of JVP and IfNotNow and Rabbis4Ceasefire I’d met reporting this story, many of whom considered the protests a deep expression of their Jewish values, viewed their comrades as the sort of community they’d never found in traditional Jewish settings, and saw anti-Zionism as a form of religious renewal. Many considered the Jewish state spiritually lost and thus were delivering a warning—the kind of prophetic admonition that is found throughout the Torah.

Not that I’ve read a lot of Torah. To be honest, what Cohen said about Jews who “are not going to be Jews in a generation” probably applies to me all too well. I speak neither Hebrew nor Yiddish. My wife is not Jewish. We raised our children Jewish, but with loads of ambivalence. I don’t belong to a shul, let alone a temple, and I often work through the High Holidays. Sometimes I think I’m the ultimate product of Jewish exile, oddly at home on the margins, more observer than participant. I consider myself Jewish, I feel Jewish, but by any definition except the one reliant on blood—the one favored by our greatest enemies—I may not really be.

And yet, here I am, daring to pass judgment on Cohen, a writer I greatly admire; on the state of Israel; and on the many members of the worldwide Jewish community, my own relatives among them, who remain committed to this ancient tradition and determined to carry it forth, and who, when their brothers and sisters were massacred, insisted on fighting back, ferociously, without apology, even when the moral cost was unimaginably high and the world roared in disapproval.

I imagine a lot of Zionists these days have been reflecting on the famous words recounted in the Mishnah: If I am not for myself, who will be for me? It’s a resonant line, the first in a neat little triad of questions attributed to Hillel the Elder. Ruth Wisse borrowed it for the title of one of her books. IfNotNow takes its name from the third of this ancient rabbi’s questions. Less frequently cited is the remaining leg of Hillel’s stool, the second query. It’s the deepest, most existential of the three. It’s the one that cuts to the very essence of what it means to be human—by far the hardest to answer: If I am only for myself, who am I?

In December 2019, the two strands that had defined the Habonim Dror youth movement since its founding half a century before I went to camp—social justice and Jewish nationalism—began to unravel. During a biennial governing assembly, three movement members advanced a proposal to reevaluate one of the movement’s pillars. “Although Zionism has historically meant many things, many of them moral and beautiful, it has also meant many other things, many of them not moral nor beautiful,” they wrote, according to Mica Elise Hastings, a longtime participant who wrote about the organization in her 2021 college thesis. “The liberation of all people is tied together and therefore Palestinian liberation & Jewish liberation are not at odds, but are one and the same!” The motion fizzled, but according to a camper I spoke to, whom I’ll call Leah, such disputes are likely to continue; now 17, she has been attending a West Coast Habonim camp—her “favorite place in the world”—since she was eight. Leah and her cohort have been talking a lot lately, sorting out their politics amid a welter of conflicting emotions. Several Habonim stalwarts, including Ofir Libstein, chair of the board of directors of Habonim Dror’s international umbrella organization, and peace activist Vivian Silver, were murdered on October 7. But for the most part, the attacks have reinforced Leah and her friends’ commitment to social justice, she told me. While participants differ as to the particulars, they “came to a pretty base-level agreement that the Israeli government is committing atrocities towards the people living in Palestine,” she said. “I also feel a lot of sympathy for the people currently living in Israel, and I feel a lot of fear for my cousin, who’s in Gaza in the military right now. I don’t agree with his views on the situation, but I also understand where he got them from.”

Leah hopes to work as a counselor this summer. She said she’s looking forward to Aliyah Bet—“Kids don’t really understand what it’s about,” she laughed—but plans to sit out another activity, the annual Israel Theme Day.

“A lot of left-wing Jews I know make all of these exceptions for Israel … because we feel afraid, and we think we know everything,” she continued. “But the writing’s been on the wall, and it’s really time to open your eyes. What Israel is doing to people in Gaza is genocide. And I think as Jews who have been through something like the Holocaust, we of all people should be able to stand against that.”

In the beginning (you should pardon the expression), Zionism made a lot of sense. “Europe was falling apart,” Dartmouth’s Magid pointed out. “You can understand Jews saying, you know, I’m fucking done with this. This exile is not good. And I’m going to take agency upon myself and adopt some Western European nationalist idea and go create this country. I totally get that. Had I been alive in the 1920s in the Pale of Settlement, it may have looked like a really good idea. It created a state, and it saved a lot of lives—and now it’s persecuting a lot of people.”

“A Jewish state, in and of itself, is actually no different than any other national project, and in principle no more objectionable,” Khalidi noted. “The problem is the settler colonialism that was involved in planting these Eastern European beings who were fleeing persecution in a country with a population that would not allow itself to be superseded. That’s the problem.”

Has Zionism lost the argument? Yes and no. It certainly won when it mattered most—when Jews in Europe were being slaughtered en masse, and when the nations of the world, including the United States, refused them sanctuary. It won when the U.K. was at last abandoning its imperial vision, drawing borders, and bestowing nationhood. And it won again, in a squeaker, when the United Nations gave the nod to partition.

And then, gradually, it began to lose. Nation-states—and, yes, armed resistance movements—exercise power in ways that often shock the conscience. And to the extent that they ask our assent, or perhaps our complicity, we all grant or withhold it as our own spirit dictates. When so moved, we can hit the streets in protest. But that’s about it. If countries just curled up and died—dissolved their parliaments, folded up their flags—because they’d committed actions that were immoral, indecent, or murderous, the world map would be unrecognizable. Israel isn’t going anywhere, whatever its enemies hope or its supporters fear.

“The way Israel is spoken of, especially by protesters, reminds me of the old Soviet joke: It works in practice, but does it work in theory?” Cohen said. “Israel works in practice, for Israelis. It doesn’t need to justify itself theoretically. The country is there. On the maps. On the ground. And social media is not going to change that. Iran might, but social media, no.”

Facts on the ground, in other words. This might well serve as the Zionist creed, fitting for a place that was for most of its history more mental construct than physical reality. This notion-turned-nation survived, and in many ways thrived. It has the strength now to turn Gaza to dust; to create unimaginable bloodshed; to rebuild its iron walls, real and figurative; to defy world opinion, and carry on. It’s also strong enough, I humbly submit, to chart a different, better course.

I’ve spoken to dozens of anti-Zionists over the past few months, and not a single one thought Israel should cease to exist. Most, convinced that ethnic discrimination and democracy were fundamentally incompatible, seemed to favor a return to the binationalist ideal advocated by Stone and others. And why wouldn’t they? American Jews are justifiably proud to live in a successful multiethnic democracy, imperfect though it is. As citizens of a nation in which Jews are a distinct minority, we owe our well-being, our prosperity, and, yes, perhaps our existence to the tolerance, openness, and egalitarianism of our system of government and our neighbors. No wonder we shudder at Israel’s chauvinism, its exclusionary nationalism, its oppression. It’s all too obvious how we’d fare if the United States followed Israel’s lead in reserving power for an ethnic or religious majority. Seen in this light, what’s surprising isn’t that some American Jews are anti-Zionists; it’s that many more aren’t.

Israelis, of course, tend to view the one-state solution as a death sentence, insisting that only a Jewish demographic majority, maintained in perpetuity and already at a terrible price, will guarantee Jewish survival. The Middle East is a “rough neighborhood,” as they often point out. Maybe they’re right. Maybe Palestinians and Jews, having lived together peacefully for centuries, will never again reach a fair accommodation. Maybe coexistence is a fantasy, and the bloodshed will be repeated again and again, each time with more deadly weaponry, until the iron wall finally holds. Then again, the wildest dreams have come true before. Sometimes, they arise out of the most brutal circumstances. “If you will it,” as Theodor Herzl famously said, “it is no dream.”