The case for impeaching President Richard Nixon was not open and shut, at least as far as the American public was concerned. When Gallup first started tracking opinion on impeachment shortly after the televised Watergate hearings began in June of 1973, only 19 percent of respondents believed the president should be removed from office; by August of the following year, when Nixon announced his resignation, that number had jumped to nearly 60 percent. It was a stunning fall for a president who had, less than two years earlier, won 49 states in a blowout reelection victory and whose approval rating approached 75 percent only a few months before the hearings began.

Could the same thing happen today? For several months, prominent advocates for impeaching Trump have made that case—and recent polls are bolstering it. Public opinion has shifted dramatically since House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced an impeachment inquiry last week, with support for impeachment drawing even, or sometimes outpacing, opposition to it. While a clear majority does not yet favor removing Trump from office, Watergate provides a number of clues about the president’s fate over the next year.

According to The Battle for Public Opinion, sociologists Gladys and Kurt Lang’s definitive but long-out-of-print book, the Watergate scandal took a long time to make an impact on the public. In TV coverage during the 1972 campaign, it received attention comparable to the Vietnam War and the Paris peace talks. But voters didn’t care. “News coverage, then, had created awareness of Watergate, but this did not translate directly into a politically relevant response,” the Langs wrote. “Watergate never became linked in most people’s minds with Nixon’s fitness to be President. It did not appear to intrude directly into people’s lives. While few would consider illegal electronic eavesdropping and political sabotage to be acceptable political practices, the crime was perceived as that of politicians against other politicians and thereby too remote from everyday concerns to agitate the ordinary voter.”

It wasn’t until after Nixon’s landslide victory that the tide began to change. Nixon’s popularity peaked shortly after his inauguration, in February of 1973. By April, nearly half of all voters were convinced that he had prior knowledge of the Watergate break-in and that he was not being truthful to the public. The historical narrative, fueled by All the President’s Men, largely credits the media for taking down a crooked president, but the Langs came to a different conclusion in 1983. While early media coverage, both on television and in newspapers like The Washington Post, had increased public knowledge of the scandal, by 1973 “the media ceased in any sense to act as prime movers on Watergate.”

Instead, it was Congress that influenced the public and led to Nixon’s downfall. While the Senate hearings themselves “had little effect on perceptions of Nixon’s guilt, they did make impeachment more acceptable… once the clear and convincing ‘proof’ had been produced,” the Langs wrote. The hearings revealed that Nixon had taped all conversations in his offices, leading to a battle between Congress and Nixon to hand over the tapes, which, in turn, led to the Saturday Night Massacre in October. Nixon would eventually release edited transcripts of the tapes in April of 1974.

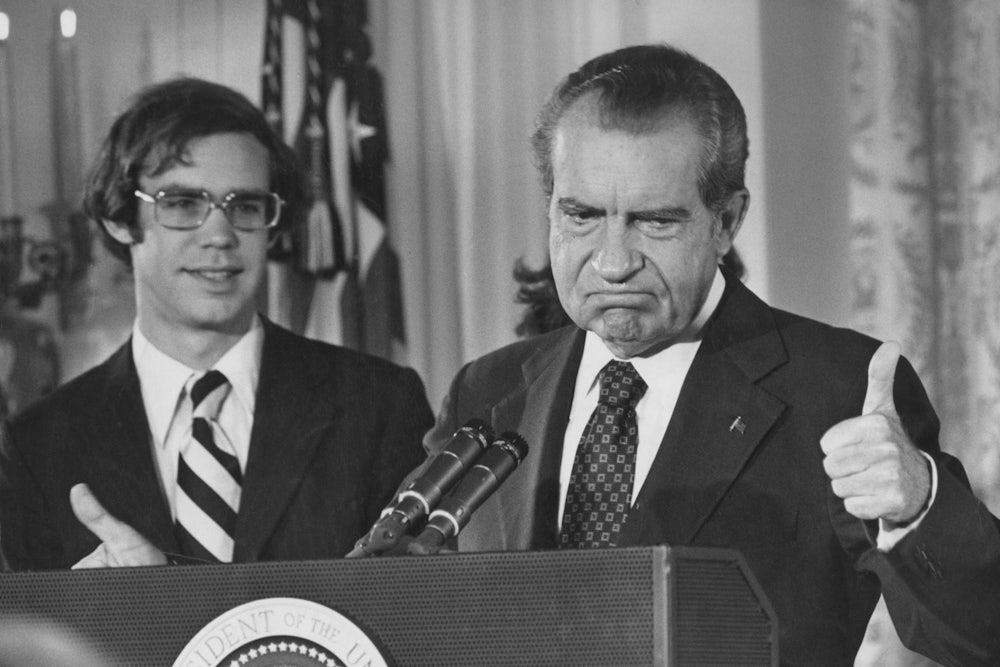

Over this period, support for impeachment grew steadily, but it wasn’t until the House Judiciary Committee recommended impeachment in July of 1974 and the Supreme Court ordered the release of the tapes—including the “smoking gun”—that public opinion shifted dramatically in favor of removing Nixon. “When that tape came out and members of Congress heard it, it was black and white what the president was trying to do,” Julian Zelizer, a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton, told me. “He could lie a million times about it and his supporters could explain it away but in the end you could hear exactly what was going on.” After the release of the “smoking gun” on August 5, 1974, a third of Republicans and over half of independents supported impeachment.

Trump has two firewalls that Nixon did not: party loyalty and conservative media. “It was such a different time,” Thomas E. Patterson, a professor of government and the press at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, said. “If you go back to 1973 and 1974, that was the low-mark in terms of party loyalty. There was quite a bit of dissatisfaction with both parties, which took a different form than it does today. You had a real mushrooming in the early ’70s of the number of independents—and they were really unanchored. Split-ticket voting was very high in that period. When you look at today, you get a lot of dissatisfaction with the two parties but party loyalty is hardened. Split-ticket voting has really collapsed in the last 25 years or so.”

Today, the number of independents is still high, but most voters reliably vote for one party. “There are fewer persuadable voters—not that there are none,” Amy Fried, a professor of political science at the University of Maine, said. “But to the extent that people are closely attached to a political party, they’re not going to change their views.” This, the Langs found, was also true during Watergate: Republicans and Democrats who had closely followed the scandal were dramatically less likely to change their opinions than those who were less interested. But there were more Americans in the undecided column than there are today.

The question, then, is whether Trump’s support among Republicans will eventually erode. This would almost certainly require the conservative media to turn on the president—to stop feeding right-wing voters misleading or downright false narratives in his defense. That may be too much to expect. But as Nixon wrote in his memoir, he knew that “the main danger of being impeached would come precisely from the public’s being conditioned to the idea that I was going to be impeached.” Trump’s removal doesn’t look inevitable today, but neither did Nixon’s until the very end. With Democrats now united on impeaching Trump, the conditioning of the American public is well underway.