Daniel Defoe, that indefatigable hack, published Journal of the Plague Year in 1722. Writing about the bubonic plague sweeping through London in 1665, when Defoe himself was no more than five years old, he characteristically, and cannily, presented his fiction as nonfiction, an eyewitness account filled with “the shrieks of Women and Children,” blazing comets, and ghosts walking upon gravestones.

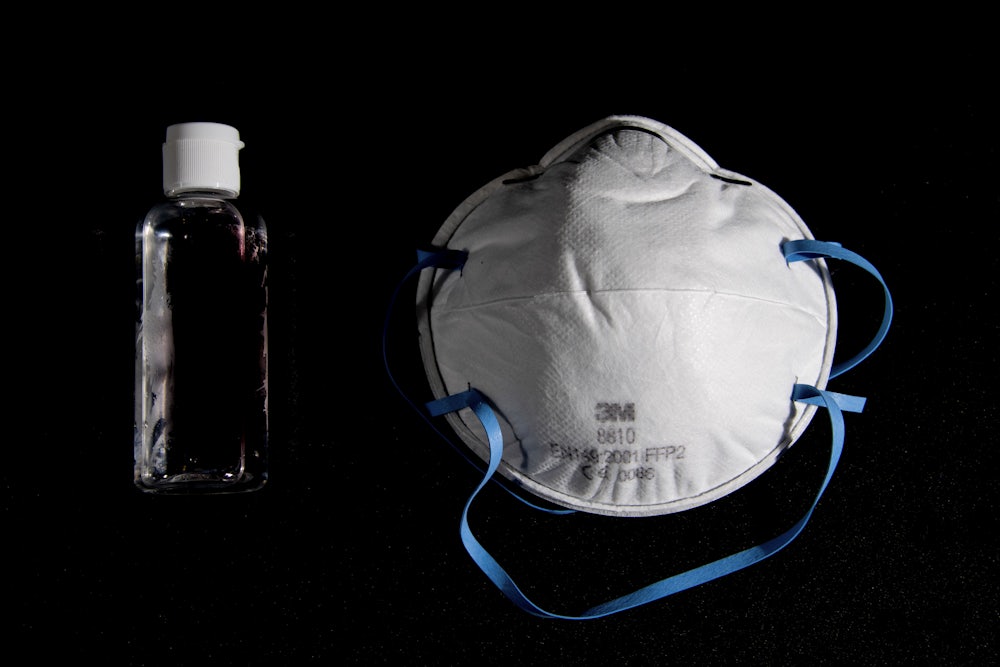

Our experience of dread, of the uncanny forcing some of us back into our homes, and many of us into our alienated inner lives, is a little different. The pandemic of 2020 projects its power over us in real time, but unless we’re directly affected—or infected—it comes across to us in means primarily visual and textual. Eerie panoramas of deserted airports and Instagrammable tourist sites; close-ups of surgical masks in turquoise green and powder blue; images of figures in hazmat suits cleaning up our endless material spill.

The scrolling feeds on social media and the live updates on websites pull us together and yet, in the same moment, effortlessly cast us asunder. What is the status of your passport? Do you have health insurance or do you work in the gig economy? If you have children, what kind of school do they attend? Are you in a rich country, a poor country, or in between?

Donald Trump, we know, has banned travelers from Europe. Narendra Modi, who has specialized in turning Indian Muslims into foreigners, will now not allow foreign tourists and diaspora Indians to enter his nascent Hindu nation. Fossil fuel companies are maneuvering for a bailout, the stock market seems to have received one already, and the United States lags behind Vietnam in terms of testing those sick. Even the name of the virus mutates: Covid-19, novel coronavirus, and—for some in the U.S.—the Wuhan virus. In China, they’ve started calling it the American virus.

A week before private educational institutions in and around New York began suspending classes and moving them online, some of the students in my fiction workshop confessed to feeling “freaked out” by the novel we were reading—Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel. In the book, a virus called Georgia flu—Georgia the nation, not the U.S. state—wipes out a significant portion of the world’s population, triggering an apocalypse and returning North America to the state of medieval Europe. As in England in the aftermath of the 1665 plague, a group of traveling artists move by horse and foot through the Midwest in the aftermath of the Georgia flu. They struggle for survival, of course, but in what is perhaps the most distinctive, and moving, feature of Mandel’s novel, they also privilege art, performing Shakespeare and classical music in a landscape blighted by the collapse of modernity. What does it mean that we’re reading this novel as the coronavirus spreads? I asked. That you have superpowers? a student responded.

I didn’t tell them—or did I? I can’t remember because I’m as addled by the changes as anyone else—that the novel I’ve been putting finishing touches to has a virus of its own, something India’s nationalistic media apparatus names the China flu. That the book includes a smog-filled Delhi where people go around in a crazy assortment of face masks. And that it features a luxury cruise ship kept in quarantine, released, and then embarked upon by a mysterious, coughing passenger. These are all details that surfaced in my mind years before the coronavirus made its appearance; unlike in Station Eleven, whose Georgia flu disrupts a way of life otherwise considered normal, the virus in my own book is just one more manifestation of a larger, global crisis that has long been evident and whose more obvious, but by no means exclusive, effects include inequality, precarity, and climate change.

Writers in the twentieth century, even those from privileged, Western backgrounds, were capable of making these connections with relative ease. A disease was not just a disease, a one-off event, but an eruption of symptoms within a diseased society. Instead of being a punishment from above, as some in Defoe’s novel interpreted their seventeenth-century plague to be, it was, in the hands of writers like Albert Camus and Thomas Mann, an internal condition made manifest externally, a collective version of Freud’s return of the repressed.

For Camus, writing The Plague in the 1940s, sickness was political and moral as much as physiological. His version of the bubonic plague is also fascism, the sealed gates of the Algerian coastal city of Oran, where the novel is set, an allegory of the Nazi occupation of France. Like fascism, Camus’s plague does not arrive out of nowhere. There are many signs of the impending crisis: the dead rats in factories, warehouses, and apartment buildings. “It was as though the very soil on which our houses were built was purging itself of an excess of bile, that it was letting boils and abscesses rise to the surface, which up to then had been devouring it inside,” Camus’s narrator, Dr. Rieux, writes. Yet these manifold traces are ignored by complacent authority figures until the plague has broken out and the town has to be closed off from the larger world. Within the confines of Camus’s closed town—closed and confined in ways beyond Camus’s vision, given that it is set in French-occupied Algeria but features not a single Arab character—the characters must come to terms with the relation between individual survival and collective solidarity.

Mann, writing just before the first of the great wars that would plunge triumphant, industrialized, and colonizing Europe into despair and destruction, is even sharper in his vision and his indictment of respectable bourgeois Western society. Aschenbach, the elderly protagonist of Death in Venice, is a celebrated writer, revered in Germany. On holiday in Italy, he becomes infatuated with a teenage boy called Tadzio, stalking him around a Venice devoted to commerce, where the sweetish, medicinal smell of germicide and rumors of plague are suppressed vigorously by all those with a stake in the tourist trade. Only an English clerk admits the truth, tracing a history of the sickness that has arrived in Europe.

For the past several years Asiatic cholera had shown a strong tendency to spread. Its source was the hot, moist swamps of the delta of the Ganges.... Thence the pestilence had spread throughout Hindustan, raging with great violence; moved eastward to China, westward to Afghanistan and Persia; following the great caravan routes, it brought terror to Astrakhan, terror to Moscow. Even while Europe trembled lest the specter be seen striding westward across country, it was carried by sea from Syrian ports and appeared simultaneously at several points on the Mediterranean littoral; raised its head in Toulon and Malaga, Palermo and Naples, and soon got a firm hold in Calabria and Apulia.

Mann’s plague, though, is internal as much as external, mutating through the repressed desire that lurks beneath Aschenbach’s veneer of wealth and respectability. That desire is present in the changes Aschenbach makes to himself through the course of the novella, dyeing his hair and getting his face painted, attempting vainly to render himself more youthful and closer in age to Tadzio. Increasingly a voyeur and a caricature, someone who has brought his own kind of sickness to Venice, Mann’s protagonist is a somber reminder of the infection within, an eerie forerunner of the elite who populate today’s ruling classes.

But Aschenbach himself is ultimately a product of his environment, of a European bourgeois order premised on the idea that everything else—the young, women, working classes, the non-Western world—exists largely to satisfy its appetites and desires. In both Mann and Camus, this order is also based on denying material evidence, whether this be the smell of sickness, dead rats, or inequality, something the authorities of our own time seem to be equally well versed in. The swing from denial to quarantine, from self-serving individualism to the declaration of emergencies, is the response of those who can’t bear to look at the world as it is, of a world in a long, perpetual crisis that the pandemic has only made more visible. An acknowledgment of that might be the starting point for both imagination and collective action.