The following is a lightly edited transcript of the January 21 episode of The

Daily Blast podcast. Listen to it here.

Greg Sargent: This is The Daily Blast from The New Republic, produced and presented by the DSR Network. I’m your host, Greg Sargent.

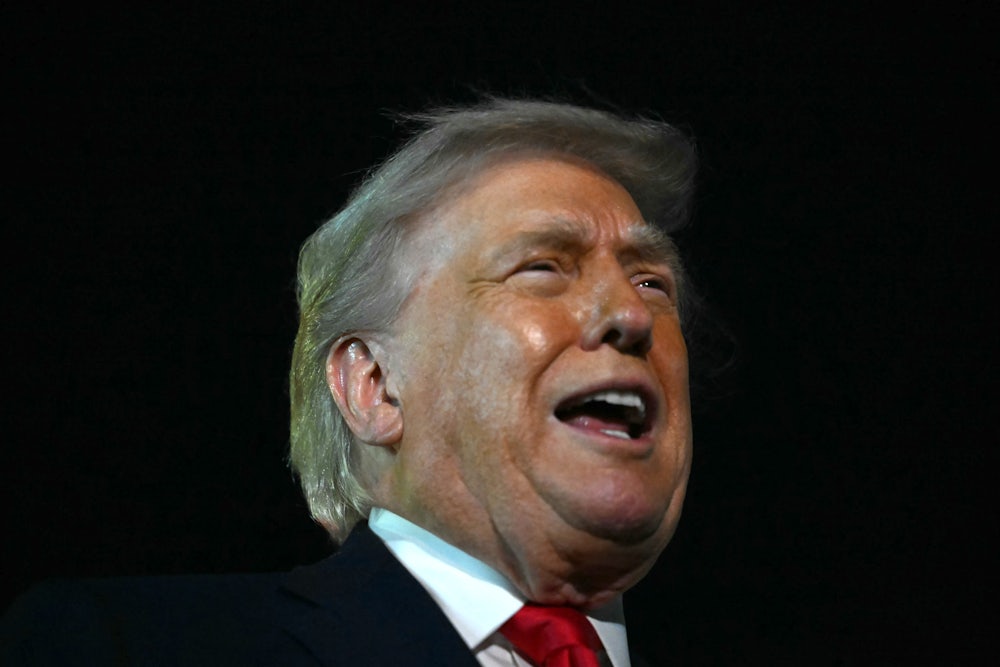

Over the weekend, the news broke that President Trump sent a deranged text to Norway’s prime minister about his desire to seize Greenland. In it, Trump linked his failure to win the Nobel Peace Prize to the possibility of taking Greenland by military force. It turns out that wasn’t a one-off. Trump said something very similar in remarks to reporters on Tuesday.

And all this has prompted at least one medical specialist to sound the alarm. That notion in turn was amplified by a Danish politician who called Trump “mad and erratic.” Which got us thinking about how all this madness must be getting perceived by the rest of the world. So we’re talking about this to Elizabeth Saunders, a political scientist who specializes in international relations and has a great new piece for Foreign Affairs magazine arguing that Trump is leading us into a future of primitive anarchy. Elizabeth, nice to have you on.

Elizabeth Saunders: Thanks. Good to be here.

Sargent: So Trump has been talking about taking over Greenland, and everybody has already seen the text that he sent to Norway’s prime minister. I’ll read the key part:

“Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize for having stopped 8 Wars PLUS, I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace, although it will always be predominant, but can now think about what is good and proper for the United States of America.”

Elizabeth, the idea that Trump stopped eight wars is pure fiction, but from an international affairs perspective, what does it mean that Donald Trump is talking this way to the leader of another sovereign country?

Saunders: Well, and an ally—two allies, at that, who are essential to the defense of Europe and Ukraine. It’s astonishing. And leaving the “eight wars” fiction aside—“eight wars plus” fiction aside—it’s not that unusual for leaders to say things behind closed doors or even in diplomatic cables that are strongly worded and so forth, even leader-to-leader.

But I think this level of pettiness, and the accusation that Norway is somehow responsible for him not getting the Nobel Prize and that that should matter in the matter of Greenland’s sovereignty, is kind of beyond anything I think any of us have seen or even can speak about in history.

Sargent: Just about the pettiness of it—I think Donald Trump actually sees this as a really world-historical injustice that he’s been denied this prize, don’t you? I think he really sees it that way.

Saunders: I try not to predict with too much confidence what’s going on in Donald Trump’s mind. I do think he just has no love for the Europeans, and his National Security Strategy talks about making Europe’s civilization great again in so many words. And I think that every time Europe talks about the rules-based order, it must drive him crazy. So maybe he thinks it’s a world-historical injustice; that’s entirely plausible. Maybe he’s just petty.

But I think fundamentally, he just does not respect Europe, and he’s been very consistent for decades about how he doesn’t like multilateral alliances and he doesn’t believe in multilateral trade agreements. These are the bedrock principles of Europe. And now he wants Greenland.

And he’s essentially saying: I am going to violate ... the most fundamental norm of the post-1945 order, the one Putin violated in 2014 and 2022 in Ukraine. I’m going to take Greenland away from an ally. And that is something that I think is shocking to most analysts who ... I mean, speaking only for myself, hardly anything shocks me.

Sargent: Yes. And I want to get into your great piece about this at the end of this discussion.

But first, let’s listen to Trump bring this up one more time with reporters. Here’s him talking about it. The “María” he refers to here is María Corina Machado, the Venezuelan leader who gave her Nobel to Trump. Listen.

Donald Trump (voiceover): You know, I should have gotten the Nobel Prize for each war, but I don’t say that. I saved millions and millions of people. And don’t let anyone tell you that Norway doesn’t control the shots, okay? It’s in Norway. Norway controls the shots. They’ll say, We have nothing to do with it. It’s a joke. They’ve lost such prestige. Got all ... that’s why I have such respect for María doing what she did. She said, I don’t deserve the Nobel Prize. He does.

Sargent: So again, what he’s primarily preoccupied with here is whether Norway denied him the Nobel. And also, I think Trump appears a bit confused about how prizes work, but it’s a little hard for me to avoid noticing that he’s sticking with this line. He’s got to think on some level, somewhere, that this makes strategic sense.

Saunders: Well, I think the Europeans are taking it very seriously. And so whatever he’s thinking, they’re no longer treating it as a remote possibility. I mean, the speeches this morning in Davos by Macron and Mark Carney of Canada were truly astounding.

Carney’s in particular essentially declared the rules-based international order dead, which many of us have already done. But for the Canadian prime minister to say it out loud on television at an international forum on television is really crossing a Rubicon, I think.

As for what Trump is thinking, I think what Trump wants is Greenland. What he’s thinking is he wants Greenland. And it hasn’t been given to him in the easy-peasy way that he thought it would be, maybe. I don’t think there’s any plan.

I have been wondering, what would even a peaceful U.S. annexation—leaving aside all the reasons why that’s not going to happen, but for argument’s sake—what does it look like for the United States to “acquire” Greenland?

Are we going to run Greenland’s courts? Are we going to administer Greenland as a territory? Are we going to appropriate money for its infrastructure? The people of Greenland do not want to be part of the United States, so it would be under hostile terms.

There is no reason strategically why this should happen. We have an ally. Their interests and our interests should align and have aligned for 80 years. And they do all those things.

Now, Greenland may choose to become independent of them, but that’s a matter for Denmark and Greenland to work out. It’s inconceivable that it would be more strategically valuable for the U.S. to “own” Greenland than it would be to keep the status quo.

Sargent: Well, maybe you could clarify for listeners what the current arrangement is, because we actually have access to Greenland in many ways, and pretty much everything Trump wants, presumably, he could have right now. Can you talk about that?

Saunders: Yeah, sure. I mean, I think there’s a very useful contrast here with the new Venezuelan regime. So we have this well-known concept called the principal-agent problem, where if you are a principal and you want an agent to do something for you, that’s great. But if you don’t want to have to monitor them closely, they’re probably going to slack off or do it a different way.

And so that’s what the risk is in Venezuela. The Venezuelan government—the Delcy Rodríguez government—is only going to promise to give Trump what he wants while there’s U.S. military pressure offshore. The minute that goes away, they go back to running the illicit economy and so forth.

And the reason is because the principal and the agent have divergent interests. They want to make money, and we want the illicit economy to go away, or to have the oil, or whatever it is that Trump and his Venezuela-toppling acolytes want out of Venezuela.

The opposite is true in Greenland. It is the rare case where acting through an agent is actually far more efficient because their interests are complete—or were until last week—completely aligned. There is no reason why you can’t act through Denmark and get what you want—and if you want to be crass about it, at lower cost.

Sargent: Yeah. And the administration, just to your point that you raised earlier, they have not laid out an actual plan for taking it over, whether it’s by buying it or by taking it by force ... what happens down the line? They don’t seem to feel any obligation whatsoever to explain why he’s doing this. And just to sort of tease out your point a little more, it would actually be worse for us to acquire it than to not acquire it. Isn’t that your point?

Saunders: Yes. I mean, it is. What I’m suggesting is the reason you hire an agent to do stuff. To run your factory or to … this is part of life. It’s a term that comes from economics. You do it because maybe they have expertise that you don’t have, or maybe it’s just more time-efficient or cost-efficient to delegate a task to an agent.

The difficulty is if the agent has different preferences than you: maybe they want to slack off, maybe they want to take kickbacks, maybe they want to run a drug side business, whatever it is. I mean, that’s essentially the Venezuela problem. You’ve got to monitor them very closely or else just do it yourself. Who among us has not had the [thought], Ugh, I’ll just do it myself.

In Denmark, you have an agent who is already doing it exactly the way every U.S. administration until now—and probably everyone into the future were it not for Trump—would choose to do it. They’ve said, We used to have more troops there, if you want more troops there, great.

Most world leaders, most American presidents can only dream of that kind of access. And so ... it will be far more costly. The biggest reason why—and the lesson that we learned in Iraq, and we’ve learned it over and over and over again in interventions going back a century—is that we would be essentially occupying territory where the people don’t want us. That’s also happening in Minneapolis, by the way.

Sargent: Well, yes, totally different reason for the occupation, of course. To your point about how this is just batshit insane, let’s check out what a Danish politician, Lars-Christian Brask, said about Trump. Listen to this.

Lars-Christian Brask (voiceover): You know, if I could come with some advice, it would be for the Senate and the House to start to take control of the political power in America, because with this mad and erratic behavior, you know, you have to ask the question, is the president capable of running the United States?

Sargent: It’s interesting how from an international perspective, people don’t quite understand why other American politicians and institutions are letting Trump run wild this way without any serious constraints. It must look extremely baffling to the rest of the world. Is that something you’re seeing in other international coverage?

Saunders: Yes. I’ve been asked this question by international journalists as well. And I think you have to hear—you have to understand the difference between Trump 1 and Trump 2.

So in Trump 1, there were still people around him who would step in and check his most extreme impulses. They may have enabled many extreme policies, but they stepped in. I mean, he mused about buying Greenland in 2019. There were still some constraints around him.

Presidential advisors are a very important check on the president’s ability to use military force and an important political constraint. They can go public. They are political actors in their own right. And it’s the subject of my most recent book, The Insiders’ Game.

In Trump 2.0, he has constructed a White House apparatus where nobody will say no to him. He handpicked people that will be sycophantic, will say yes. And so there are effectively no checks on his foreign policy.

I mean, I wrote in Foreign Affairs in June that we have “the foreign policy of a personalist dictatorship.” So I think Trump is Trump and has always been Trump. He’s always disliked NATO and alliances and multilateral trade. He may have wanted Greenland for ... long before 2019.

What you have now is Trump in a completely permissive environment. And so, you know, the constraints have been defanged. Congress is completely supine. And the Supreme Court has given him immunity for his official acts. So there’s really no shadow of any constraint on him now.

Sargent: One Republican senator, Thom Tillis of North Carolina, has been basically making that point. He’s been forcefully criticizing Trump. He told Punchbowl News in a new interview that he’s considering using his power to try to slow down this madness from Trump on Greenland, including trying to block nominees in committee and slow the Senate down in other ways.

Tillis called Trump’s threats toward Greenland and Denmark the “betrayal of a friend.” He recently said, “I’m sick of stupid” about all this.

Elizabeth, isn’t it incredible that we don’t hear more Republicans talking like this? I mean, the Republican Party has a whole lot of people who have a genuine interest in foreign relations. Maybe we don’t agree with them on a lot of things, but they’re not completely crazy or complete lightweights either. And yet they just let all this stuff slide without a word.

Saunders: Well, the sorts of things that Tillis is talking about are exactly the way Congress used to act—and I say used to really before 9/11. They would block things in committee. They would demand answers or haul ... White House officials up to the Hill.

And it got worse after 9/11, I think, because of the delegation to presidential power. And so Trump isn’t entirely responsible for the trend, but I think he has been the one who has seized it.

Sargent: I want to talk about Dr. Jonathan Reiner, who was the cardiologist to the late Vice President Dick Cheney—former vice president. Trump’s talk about Greenland prompted him to call for action. Reiner said this on Twitter:

“This letter, and the fact that the president directed that it be distributed to other European countries, should trigger a bipartisan congressional inquiry into presidential fitness.”

I thought that was pretty eye-opening and obviously very true. What did you think?

Saunders: Well, I mean, I’m not a doctor, so I defer to those who are. I definitely—I think it’s hard to disentangle the permissive environment of Trump 2.0 from the obvious signs of aging. Trump is Trump. Obviously, Biden had issues of his declining health.

And not to excuse what his advisers did by any stretch, but their approach was to keep him away from the public eye. Trump’s advisers’ approach is just to let him loose. And so there is a sort of loose-cannon feeling to it now. I think you’re seeing this on so many fronts.

The other vehicle for really constraining him that would maybe stop him in his tracks is if the Republicans went after him for his attacks on Jerome Powell. Because that is an existential threat to the Fed’s independence. And that affects the whole economy.

It’s almost so esoteric that it’s ... and it’s not military force, [so] it’s sort of easier politically, I would imagine, for Republicans to be brave about.

But if the Twenty-Fifth Amendment was not invoked on January 6, I don’t see how it could be invoked over Greenland. Even though annexing Greenland is such a historic breach of trust with our allies, makes no strategic sense at all and is just clearly a fiasco waiting to happen.

Sargent: Well, just to close this out on that point, there may be one way to understand what he’s doing. And it goes to what you wrote in your piece for Foreign Affairs, which talked about how Trump is really breaking this basic principle that should be undergirding things: that you just don’t redraw borders by force. I think maybe what he’s trying to do with all this is break that principle. Does that make sense to you?

Saunders: Yes. I mean, there are those who would point out that the United States violates borders all the time. It did in Iraq. It has done so in Latin America repeatedly over a century. So I mean, the rules-based order has always been—I like to say the liberal international order was never fully liberal, never fully international, and never fully orderly.

And the U.S. was always the one that could break it and so forth. And we annexed all kinds of territory, and we don’t treat the people equally. American Samoa, for example, Puerto Rico. So in that sense, it’s not so much of a direct break.

The fact that he’s not even rhetorically defending the principle of territorial order is different. You can accuse previous presidents of hypocrisy because they were trying to uphold the principle while violating it. He’s not even trying to uphold it. He’s essentially siding with the Putins of the world who feel it can be violated and shouldn’t ever really exist.

Plus you also have the ... you’re attacking your own NATO ally, which, that is a new dimension. And I think that is what really makes it the potential death blow to whatever remains of the rules-based order.

Sargent: So what’s going to happen, Elizabeth?

Saunders: My goodness. I still think when push comes to shove, I have a hard time imagining what even a military landing on Greenland or takeover or annexation—I have a hard time connecting the dots from where we are now to the U.S. owns Greenland.

That said, absolutely nothing would surprise me. And I do think that for the Europeans and for Canada, this is a real—if the Munich Security Conference was a shock wake-up call, this is the turning point.

Sargent: Well, Elizabeth Saunders, that was certainly harrowing enough, but, talk about realism, you gave us a good dose of it. Great to talk to you. Thanks so much for coming on.

Saunders: Thank you for having me.