If there is one political lesson Republicans

have taken to heart since 2016, it is that there is no crossing Donald Trump.

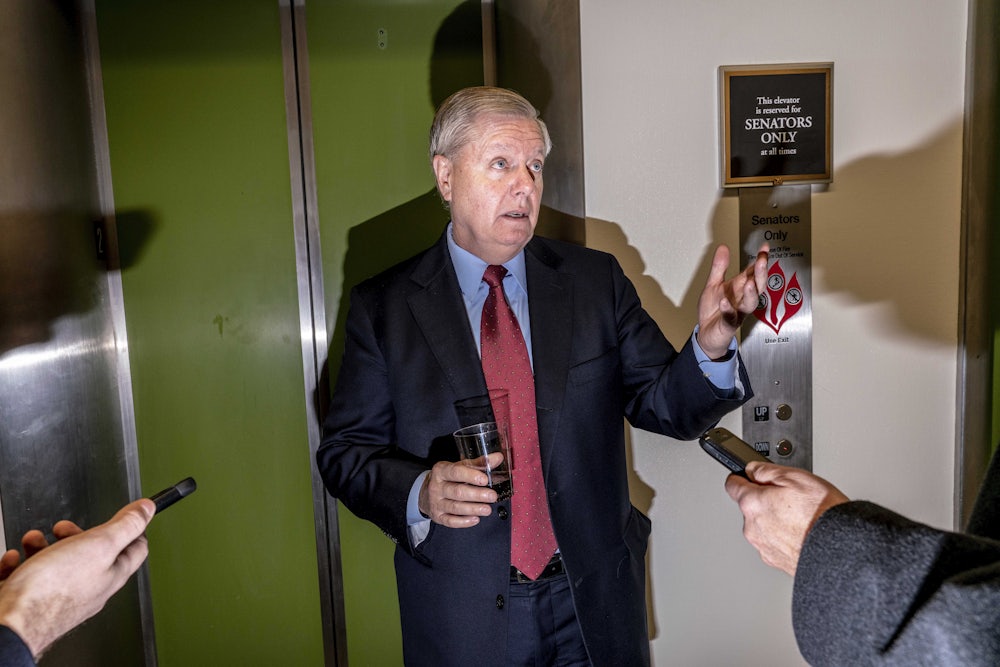

Perhaps no GOP official better represents Trump’s death grip on the party than South Carolina’s Lindsey Graham, who started off as Trump’s bitter

enemy—calling him a “kook” and “unfit for office”—before becoming his most

ardent loyalist in the Senate, declaring at the outset of Trump’s impeachment

trial, “I’m not trying to pretend to be a fair juror here.” The payoff

ostensibly comes this November: Buoyed by the president’s support in a state

that went for Trump by 14 points in 2016, Graham is expected to win a fourth

term.

But in an election that is poised to be a referendum on the broadly unpopular president, and in a state where Republican policies have worsened the suffering of the working class, Democrats sense an opportunity for an upset.

While South Carolina leaders tout a booming coastal tourist industry and new manufacturing plants lured by cheap nonunion labor and tax breaks, the state’s residents trail the country in most measures of quality of life. South Carolina’s underfunded public schools rank among the worst in the nation for teachers and students. While South Carolina’s unemployment numbers are low on paper, in reality wages have lagged behind inflation and soaring rents in cities like North Charleston, which faced the highest home eviction rate of any American city in 2016. The capital city, Columbia, was not far behind, at number eight.

Meanwhile, South Carolina’s Republican-controlled government routinely bludgeons its most vulnerable residents, particularly in the rural counties straddling Interstate 95. Political leaders here have compared poor people to stray animals, sent children to crumbling schools aboard flammable school buses, and rejected key components of the Affordable Care Act that could have prevented needless deaths.

Amid the wreckage, Democratic leaders looking to unseat Graham have pinned their hopes on a consummate party insider named Jaime Harrison.

Harrison is a former state party chair who worked in the office of Democratic power broker Representative Jim Clyburn. He represents the first credible threat to Graham’s tenure in nearly two decades, and his personal story speaks to the struggles of many South Carolinians. Some early polling in the state has shown him within striking distance of the GOP incumbent, and he has been raising funds at a pace that almost rivals the Graham electoral juggernaut.

Harrison’s national fundraising pitch stresses Graham’s sycophancy to the president. But if Harrison is going to win in November, he will need to do more than wag his finger at Graham for becoming Trump’s golfing buddy. He’ll have to ramp up voter turnout and inspire an electoral uprising on a scale not seen in this state since Reconstruction.

Can Harrison pull off this near-miracle? Thus far, his platform hews to the moderate party line that South Carolina Democrats have long held. He wants to make college affordable but not free, and to fully implement Obamacare but not Medicare for All. His early interviews and campaign ads have highlighted issues like affordable health care, rural infrastructure, and school inequality—all dire problems in the Palmetto State. Four rural hospitals have closed since 2010, leaving entire counties without access to basic medical care. Harrison has drawn a direct connection between these injustices and the austerity policies of state and national Republicans.

In one of his first campaign videos on Facebook, Harrison told a story about campaigning door to door in an unspecified rural community. According to Harrison, he knocked on the door of a shotgun house and was greeted by an older black man who cut him off just as he was launching his campaign pitch. The man told him his road had been unpaved dirt since the Reagan administration and that he wasn’t interested in talking about politics until someone—Republican or Democrat—came along and fixed his road.

“That road is symbolic for so many things for so many of us across this state,” Harrison said in the video. “It might not be a dirt road for the people in Allendale, but it could be schools. It might not be a dirt road for the people in Bamberg, but it could be a hospital.”

By any measure, the Harrison campaign will be the underdog as the well-funded Graham machine lurches into gear for the general election. South Carolina Democrats in recent election cycles have typically mustered a slate of moderate Democrats for Republican-held seats—a strategy that’s mostly led to crushing defeats. So Harrison’s campaign hinges on two questions: whether a moderate strategy is the best way to defeat Trump’s Republican Party, and whether Trump’s loyalists, like Graham, will pay a price for embracing a historically unpopular president.

While Graham and Harrison are very different politicians, they both come from humble backgrounds.

Graham has been refining his bootstraps campaign narrative over the course of his political career. He grew up in the upstate mill town of Central, hanging out at his parents’ bar and running the basement pool hall starting at age 12. Through most of his childhood, he slept in a cramped room behind the family business and saw the mill workers who patronized the bar as his extended family.

His parents died while he was attending the University of South Carolina, leading him to file papers to qualify as his younger sister’s adult guardian and formally adopt her. In a message that’s resounded with the powerful evangelical voting bloc, Graham has credited religious faith and extended family for getting him through hard times. “I don’t know what people do when they don’t have a family like ours, when they don’t have aunts and uncles and cousins who don’t need to be asked for help,” Graham wrote in his 2015 autobiography, My Story.

Graham’s life makes for a compelling political

origin story. But like other variations on the log-cabin myth, Graham’s

narrative tends to stress personal charity and his own gumption while eliding

the structural economic conditions—from the end of Reconstruction through the

massive resistance to school integration and the rejection of federal welfare

expansion—that have kept South Carolinians among the poorest people in the

country.

Harrison grew up as the son of a single teenage mother from rural Orangeburg and was raised by his grandparents, who he says lost their home to an unscrupulous mobile home salesman. On a recent stop in Charleston as part of his Harrison Helps Tour, in which the candidate is visiting all 46 counties in the state, he listened to a Habitat for Humanity thrift store worker talk about the growing eviction crisis in the rapidly gentrifying city. “I know the anxiety about losing your home,” Harrison responded.

Harrison is an affable public speaker with a knack for folksy one-liners, but he can also express outrage and a sense of acute dispossession that never comes across in Graham’s softer-focus reminiscences. Here, for example, is how Harrison tells the story of his grandfather, Willie Harrison, who dropped out of school in the fourth grade and spent much of his life working in construction:

“Even though he worked 50, 60 hours a week out in the hot South Carolina sun during the summers, he never had any health care … so he never went to the doctor, so he ended up having diabetes and catching it so late that they had to amputate part of his leg and toes off of one of his feet, so he ended up in a wheelchair.

“It was so hard to see my grandfather go through that whole process, which makes my fight for health care so personal for me.”

When I interviewed Harrison at a noisy upscale coffee shop in Charleston, he frequently referred back to his childhood and his family’s struggles. “I have this running theory that you are who you are as an adult based on the things you experienced as a child,” he said.

After he graduated from Orangeburg-Wilkinson High School in 1994, Harrison earned admission to Yale University, but his family couldn’t afford the tuition. He ended up paying his way through school by working for Orangeburg community pillar Earl Middleton, a Tuskegee Airman who became the first African American to own a Coldwell Banker real estate franchise in the United States.

“I felt like a Walmart kid on Rodeo Drive,” Harrison said about adjusting to life at Yale.

After college, Harrison worked in the office of then–House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn, serving as director of floor operations and executive director of the U.S. House Democratic Caucus. He later became a lobbyist for the Podesta Group, where his clients included Boeing, General Dynamics, Bank of America, and the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity.

Harrison has established himself as a corporate Democrat, like so many South Carolina Democrats before him. The state party skews centrist. To give one recent example, Democratic Congressman Joe Cunningham, who flipped a Republican House seat in the Lowcountry in 2018, has criticized Bernie Sanders and opposed pro-union bills that would have overturned South Carolina’s “right to work” law. And Todd Rutherford, the state’s House minority leader, endorsed the billionaire Michael Bloomberg, whose campaign flamed out weeks later.

After years traveling back and forth to Washington, D.C., Harrison and his wife moved to Columbia in 2013, when he ran for chairman of the South Carolina Democratic Party. He won, becoming the first African American chair in the party’s history. He was a candidate for chair of the Democratic National Committee in 2017 but dropped out to endorse Tom Perez.

As his professional résumé makes clear, Harrison is not disposed, either by personal inclination or political calculation, to run as an outsider or firebrand. Nor would he have much in the way of institutional support if he were to mount a full-throated populist campaign in this cycle of intensive conflict between the establishment and insurgent wings of the Democratic Party: In addition to falling in line with the centrist profile of most Democratic leaders in the lower South, Harrison is seeking statewide office in a state that ranks dead last in the nation in union representation, with a mere 2.7 percent of workers represented by unions.

Like other Democratic hopefuls heeding the party’s strategy in the 2018 midterms, Harrison is foregrounding the issue of health care access. He’s assailed Graham’s co-sponsorship of the 2017 bill that would have repealed Obamacare and gutted Medicaid. (The Graham-Cassidy Bill famously died at the hands of Graham’s former mentor John McCain, who took a final victory lap as a sensible conservative while Graham veered hard to the right.) But Harrison stops short of endorsing Medicare for All, saying he first wants to see the Affordable Care Act “enacted in the manner in which it was passed.”

“People in South Carolina, in the polling we’ve seen, are not for” Medicare for All, Harrison said. “If they like their insurance, they should be able to keep that. I’m not gonna stand in the way of folks doing that.”

Over the winter’s impeachment drama, it became clearer than ever that the Democratic Party is gravely hamstrung by its minority status in the U.S. Senate. After losing a Supreme Court seat, no end of federal judiciary appointments, and a series of major legislative battles over everything from campaign finance reform to carbon-emissions controls, Senate Democrats (together with House impeachment managers) failed to get so much as a single witness approved for Trump’s impeachment trial in February. The basic oversight function of Congress, together with the principle of the separation of powers, was a casualty of the brute math of the GOP’s 53-vote Senate majority.

So on top of the urgent need to defeat a more emboldened and unaccountable president, Democrats also have to recapture a Senate majority in order to have any hope of undoing the damage wrought in the Trump years. All the paths that can lead to flipping the Senate contain obstacles for the Democrats, requiring a battery of factors to break favorably in just the right way—and nowhere is that dynamic more evident than in Graham’s reelection bid. By some calculations, the Democrats wouldn’t need to pick up Graham’s seat, if they run the table in a series of other tight races involving vulnerable GOP incumbents. But because the impeachment drama is likely to cast a long shadow on most of the races—and because Graham has emerged as perhaps the most passionate Trump defender in the chamber—the months ahead in the South Carolina race will preview many of the central battles.

Harrison, for his part, could highlight key strategies future Democratic hopefuls might employ to win back the Southern states that many political observers now reflexively view as deep-red Trump country. Since the turn of the millennium, with the exception of the first Obama election in 2008, South Carolina Democrats have rarely gotten the existing Democratic base excited enough to show up en masse at the polls. That’s not a trend confined to national races: Republicans have held a trifecta of control over the governor’s mansion, state House, and state Senate since 2003.

The last Democrat who challenged Lindsey Graham, back in 2014, was Brad Hutto, a trial lawyer and state senator whose district spans some of the poorest and most reliably Democratic counties in South Carolina.

For the first time since Graham took Strom Thurmond’s Senate seat in 2003, Democrats saw a window of opportunity in a potentially vicious 2014 Republican primary. Doctrinaire conservatives had questioned Graham’s bona fides for years, lambasting him as “Flimsy Grahamnesty” on talk radio shows for his support of measures like immigration reform. Hutto was convinced that the Tea Party insurgency could finally pose a serious threat to Graham in 2014. So was Harrison, then the state Democratic Party’s chairman.

“Jaime and Congressman Clyburn, right before filing, said, ‘You’ve really got a shot at this because Senator Graham had a tough primary,’” Hutto said.

Graham steamrollered his opponents. Most postmortems attribute his handy victory to the “Graham machine”—a multimillion-dollar operation with precinct captains in every county. The insurgent Republican candidates to Graham’s right failed to coalesce behind a single primary challenger, and none cracked a half-million dollars in fundraising. Graham won his primary with 56 percent of the vote; his closest opponent got just 15 percent.

So much, in other words, for the assumption that Graham would be badly scarred in a tight primary battle. The Graham machine took charge of the general election in no uncertain terms. Graham outspent Hutto by a ratio of 26 to 1, then crushed him at the polls. Graham won 54 percent of the votes against Hutto’s 39 percent.

On paper at least, the Graham machine appears poised for a repeat performance in 2020. Graham made a show of force against prospective primary challengers again, rolling out endorsements from party leaders in all 46 counties in July 2019. Graham still must face at least one primary challenger, Joe Reynolds, a moderate Republican who has pledged to take no PAC money in the race.

Hutto said he remains hopeful about Harrison’s prospects in the general election.

“I ran against what most people thought was the reasonable Lindsey Graham, moderate Lindsey Graham, the Lindsey Graham who worked across the aisle and got things done,” Hutto said. “Jaime has the benefit of running against the Lindsey Graham who’s a cheerleader for Donald Trump.”

The email signup page on Harrison’s fundraising website features a blown-up image of Graham’s sneering face during his vitriolic performance at Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s September 2018 confirmation hearing.

“Are you with us?” the page asks. “Defeat Graham!” It’s perhaps not the most strategic choice if the goal is to raise doubts about Graham in the South Carolina electorate. In reality, Graham’s defense of Kavanaugh against claims of sexual misconduct might have been the single strongest move he made to shore up support with his base. Immediately after the hearing, he saw a 21 percent bump in his approval rating among South Carolina Republicans and Republican-leaning voters, many of them believing that Kavanaugh had fallen victim to liberal persecution. The Kavanaugh hearing also marked the point at which Graham’s public friendship with Donald Trump began to blossom.

Vice President Mike Pence has assured the Trumpified South Carolina GOP that the Lindsey Graham of 2016—who predicted that, if Trump were the Republican nominee, “we will get destroyed … and we will deserve it”—is long gone, speaking glowingly of Graham’s stalwart support for the president’s agenda at Graham’s campaign launch in Myrtle Beach in March 2019. “I have watched him stand in solidarity with President Donald Trump and our administration for a strong national defense, for less taxes, less regulation, and conservative appointments to the courts,” Pence said. Pence’s peacemaking overture also doubled as a road map for Graham’s general election strategy: Among the minority of South Carolinians who vote in statewide elections, tax cuts, court appointments, and deregulation are all winning issues.

Still, even some longtime Graham apologists saw Graham’s behavior during the Kavanaugh hearing as a moral failure. Among other things, Graham’s red-faced turn as Kavanaugh’s most vocal Senate defender lost him the support of one of his oldest friends, Larry Brandt.

Brandt, a 75-year-old attorney in the far northwestern corner of the state, hired Graham while he was still in law school to work as a clerk in the Oconee County courts. After Graham graduated law school and spent some time as an Air Force lawyer in Germany, Brandt welcomed him back to his quiet upstate enclave as a partner in his firm.

The two lawyers became fast friends. “He was very likable, he had a good sense of humor, he was quick on his feet,” Brandt said.

In his memoir, Graham praised Brandt’s skills as a trial lawyer and spoke fondly about the good cop–bad cop routine they refined as they sought to get information out of hostile or recalcitrant witnesses. “Larry is a bulldog for his clients. He never quits fighting for them if he believes they have been wronged,” Graham wrote.

In one high-profile medical malpractice case from 1987, Graham and Brandt teamed up to bring a popular doctor to court. Their client had been driving drunk when he ran off the road and was ejected from the vehicle. Emergency medical services took him to the emergency room where, according to Graham, the doctor failed to provide proper treatment despite signs of spinal injury. After staying in the ER that night, the patient ended up quadriplegic.

After a dramatic jury trial, Brandt and Graham won their client $5 million in damages, the largest medical malpractice damage award in state history at the time.

“[A] courtroom is where the lowliest victim should find justice and the highest wrongdoer receive just punishment,” Graham wrote about the case.

Graham used his earnings from the case, and his moment in the spotlight, to launch his first run for the state legislature in 1992. Oconee County was Democratic territory in those days, but Brandt said he advised Graham to run as a Republican, sensing that times and demographics were changing. Even at the cusp of the coming Republican revolution, Brandt and Graham both understood that the first-time candidate could ill afford to be depicted as a lukewarm foot soldier for the GOP.

Brandt lent his support and even his truck to Graham’s earliest political campaigns. He defended Graham when he heard rock-ribbed local conservatives badmouth him as a “Republican in name only.”

“Lindsey, even up here, is not that popular among the voters, but he’s a Republican, and that ‘Republican’ goes a long way,” Brandt said. “I’ve had people at social gatherings and bars, if his name came up, to say nonflattering things about Lindsey and that they didn’t like him. And I’ve always, until this last year, until the Kavanaugh mess came up, I defended him as being one person who was the voice of some common sense and reason and was willing to reach across the aisle and try to strike a compromise.”

Brandt told Rolling Stone in January that Graham had, in his opinion, “sold his mother to keep his job.” They were harsh words for a man who lost his mother at a young age—but Brandt said he stands by his assessment. “If you read his book, he talks about [how] he never forgot where he came from, but I submit to you that he has,” Brandt said.

Brandt donated to Harrison’s campaign and said he intends to vote for him. “Lindsey ran years ago on term limits.… It’s time that his term was limited,” Brandt said.

Graham’s campaign declined a request for comment on this story.

Since the last of the old-school “yellow dog” Democrats left office in the 1990s, Brandt’s northwestern corner of the state has been rock-solid Republican territory. This year will tell if cracks begin to show—and they’ll have to if Harrison is to have any real shot at unseating Graham. Greenville County, one of the largest counties in the state, delivered Trump a 25-point victory over Hillary Clinton in 2016 and remains a cultural center for evangelical Christians.

Harrison campaign manager Zack Carroll said he has been hearing some signs of change in focus groups this year. “One woman put it great, I thought; that it’s not just that he changed his mind. Lindsey had a total existential change. He went from calling Trump a bigot and a kook to being his best friend,” Carroll said. “We hear a lot here that ‘he’s changed’ … He’s changed, and he’s not the senator that so many folks down here voted for.”

South Carolina Democrats notched one big upset victory in 2018, flipping the state’s 1st congressional district by a margin of fewer than 4,000 votes.

Democratic Representative Joe Cunningham’s win was seen in some circles as a repudiation of Trumpism. His opponent, Republican Katie Arrington, had soundly defeated former Governor Mark Sanford—another GOP leader who’s criticized the president’s excesses and abuses—in the primary. She declared at her victory celebration, “We are the party of Donald J. Trump.”

A few other factors were in play. Cunningham’s suburban Lowcountry district had seen significant demographic shifts, partly thanks to massive migration from other states. An analysis by The Post and Courier found that Charleston County’s political shift from red to purple, and Arrington’s failure to convince moderate Republicans in the suburbs, may have spelled her defeat. With most forecasts pointing to a safe Republican victory, cocksure leaders in the National Republican Congressional Committee also ignored pleas from Arrington’s campaign to pump more money into advertising, causing her to fall behind as Cunningham went to the airwaves earlier and stayed on the air longer.

And Cunningham got a surge in the polls when it was revealed that Arrington supported offshore drilling. The idea was anathema to a coastal economy dependent on tourism, and Arrington was perceived as a flip-flopper when she recanted her original stance. Offshore drilling became a hallmark issue for Cunningham as the race moved into the homestretch.

Mika Gadsden, a progressive activist from Wadmalaw Island and state director of the advocacy group Black Voters Matter, thinks Cunningham simply got lucky. Looking at Harrison’s prospects, she said she’s not sure that health care access—the most sustained policy pitch that Harrison has mounted thus far—is a winning issue for 2020. She notes that Harrison has not yet harnessed the momentum of existing activist movements, like the teacher protest that saw 10,000 people marching on the statehouse in May 2019.

“Democrats here in South Carolina are afraid, they’re fearful,” Gadsden said. “Is [health care] a winning issue? It’s a winning issue if you want to continue to be where we were.”

Gadsen added, “I don’t know if they’re playing to win, to be honest with you.”

Harrison might find his winning issue on his statewide tour. In Allendale County, one of the poorest places in the U.S., he learned that workers at a local Archroma chemical plant were laid off due to lost market share from Trump’s China tariff. Soybean farmers in the agricultural regions of the state similarly complained about the chaos of Trump’s foreign trade policy.

“What is the real impact on those communities, the ones that when the nation has a cold they have the flu?” Harrison asked. It’s a good question, but it also puts the onus on Harrison and other pro-business Democrats to spell out concrete measures to safeguard the economic security of vulnerable workers.

One piece of news bodes well for the Harrison campaign’s viability: Moderate Democratic voters showed up in droves for South Carolina’s Democratic presidential primary in February, handing Joe Biden a critical win in the first-in-the-South primary contest. More than 500,000 voters turned out statewide, approaching the record turnout of 532,000 that delivered a win to Barack Obama in the 2008 primary.

On the night of the 2020 primary, longtime South Carolina Democratic consultant Lachlan McIntosh highlighted the turnout on Twitter. “This is really important for Joe Cunningham and Jaime Harrison,” he wrote. “This kind of trend will sooner than later make SC a purple state.”

There’s a thread of conventional wisdom about regional politics that might be termed “Southern exceptionalism.” It posits that Southern politics is somehow unusual in its reliance on racist tropes or in its insistence on courtly manners.

It’s not hard to see this reflex on display in outsiders’ depictions of South Carolina politics. National media have variously described Graham as “genteel,” a “sentient mint julep,” and (during the Clinton impeachment hearings) “a twang of moderation.”

In press dispatches and news analysis pieces, the stately old Southern order is evoked with scenes of dappled sunlight under Spanish moss–draped oak trees. With the mood thus set, curious readers are then reminded of South Carolina’s greatest legacy in our political culture: its role in starting the U.S. Civil War.

But these clichés have grown hoary. Harrison’s campaign manager, Carroll, said he sees a shift happening in South Carolina, thanks in part to what has been called the reverse Great Migration of black families returning to the South. Major cities and metropolitan areas are growing in population at breakneck speed. Recent Census data found the Myrtle Beach metropolitan area was the second fastest growing in the nation between 2010 and 2018, coming second only to The Villages retirement community in Florida.

“I think a lot of people mistakenly look at South Carolina as being like an Alabama or a Mississippi, but you look at demographics and it’s just not the case,” Carroll said. “The trends that are happening along these Southeast coastal states are pretty in line with what Virginia was 10 to 15 years ago.”

That shift could have repercussions in Graham’s bid, and any other statewide race in South Carolina—provided, that is, that voter ID and other suppression tactics introduced by the GOP state legislature don’t outweigh the state’s recent influx of new and nonwhite voters. And in part because of the stakes of the pending race—together with Graham’s recent makeover as a loyal Trump surrogate—it seems clear that, rather than serving as a sleepy backwater steeped in long-standing folkways of racial deference and exploitation, the conservative bastion of South Carolina is something much closer to a bellwether state.

Graham has shown a knack for adjusting on the fly to the party’s shifting ideological winds.

“I think he has always had an understanding of exactly how much danger he is in,” said Scott Huffmon, a political science professor and director of the Winthrop Poll who has closely studied the many permutations that have made up Graham’s political career. “As time wore on, he realized the greatest threat was definitely from within the party, and he started moving right. Even though he was called ‘Grahamnesty,’ his voting record was extremely conservative. When it became the party of Trump, he became his greatest supporter.”

Every political forecast this year has marked Graham as a safe incumbent, and Huffmon doesn’t dispute those forecasts. Harrison’s prospects look better than those of other recent Democratic candidates in the state—but he’s still a long shot.

“Jaime Harrison’s chance comes pretty much only from turnout and this being a high-profile race,” Huffmon said. “Mathematically, people who identify as Democrats could make it a real run, but they aren’t registered at as high levels, and they don’t turn out at as high levels.”

There’s a little-noted historical irony in the pending battle between Graham, the resentment-fueled white GOP incumbent, and Harrison, the black moderate Democrat. In the postbellum South, South Carolina Republicans were at the vanguard of the struggle to institute egalitarian racial policies in the former confederacy. The state party was co-founded by a formerly enslaved man named Robert Smalls who liberated his own family by commandeering a Confederate ship during the Civil War. He dubbed the Republican Party the “party of Lincoln,” and the party’s early members wrote the state’s radical 1868 constitution, which guaranteed black men the right to vote and established one of the first public school systems in the South.

After thwarting Reconstruction, Democrats clawed back power by presiding over an exceptionally vicious segregationist agenda. By the latter half of the twentieth century, the state had steered yet another race-driven political realignment, as Strom Thurmond’s segregationist Dixiecrats gave way to the race-baiting Republican politics of Nixon and Reagan, ceding the bulk of white Southern voters. It was another South Carolinian, political consultant Lee Atwater, who perfected the dog-whistle phase of the GOP’s “Southern Strategy”; Atwater’s notorious Willie Horton ad helped propel the first President Bush into office.

The GOP went from the party of black power and economic liberation to the party that suppresses black votes and opposes the rights of working people. This evolution has been in line with the course charted by the broader political economy of the Palmetto State: From plantation economy to anti-worker corporate paradise, South Carolina has rarely been behind the curve of conservative politics—it has, in fact, been a forerunner.

In this sense, the Graham-Harrison race presents a much broader picture of the future to the country’s political imagination: If the Republican Party ever does collapse under the march of human progress and the weight of a dying conservative base, it could well start here in South Carolina, as soon as November.