Why Americans Hate Politics: The Death of the Democratic Process

by E. J. Dionne Jr.

(Simon and Schuster, 430 pp., $22.95)

The United States of Ambition: Politicians, Power, and the Pursuit of Office

by Alan Ehrenhalt

(Random House/Times Books, 309 pp., $23)

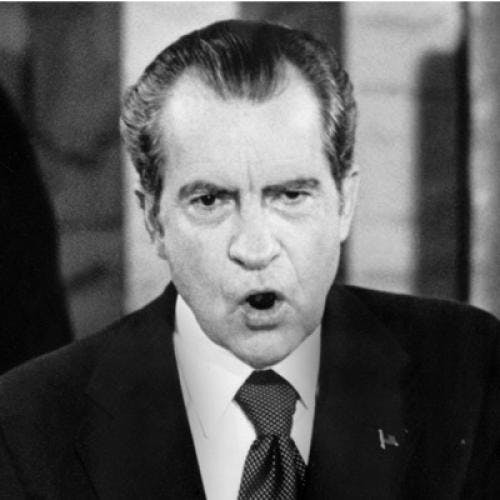

From around 1960 to around 1981, the confidence of the American people in the officials who ran the federal government declined. During the Reagan years, the decline was halted, and people became somewhat more trusting; but the improvement was modest, and it may have been short-lived. This growing mistrust of Washington politicians is often explained by the impact of Vietnam and Watergate. Those crises no doubt contributed to the problem, but they were not the cause of it.

The distrust of government increased sharply between 1964 and 1966, long before Watergate and well before public opinion turned clearly against our involvement in Southeast Asia. In that two-year span, the percentage of voters who said they trusted Washington to do the right thing “most of the time” fell from 62 percent to 48 percent. (The only other two-year period to reveal a comparably large decline was the Watergate years of 1972-74.) Between 1966 and 1968, when Vietnam was becoming a more divisive issue, owing partly to the erroneous perception that the United States had been defeated in the Tet offensive, public trust in government actually increased (from 48 to 54 percent). Moreover, the decline in trust continued after Watergate was behind us.

At the same time that Americans were losing confidence in people holding office, those offices were falling into the hands of rival parties. Divided government—a Republican president and a Democratic Congress—was no longer the exception, as it had been earlier in this century, it was the rule. Only three times in the last thirty years has a presidential election given one party (in all cases the Democrats) control of the White House and both houses of Congress. By contrast, twenty-two of twenty-six elections between 1900 and 1952 produced unified party control.

MANY OF THE prevailing explanations for divided government also turn out, on close inspection, to be of little value. One explanation, popular among Republicans, is that gerrymandering has given the Democrats a lock on the House.But that cannot be true: throughout the last thirty years, more votes have been cast for Democrats than for Republicans for the House. Even the fairest districting system would have maintained the Democrats in power. Another explanation is that the legendary advantages of incumbency have worked to protect the party—specifically, the Democratic Party—that happened to be in power when incumbency became so powerful. But when there is an open seat in the House, that is, when there is no incumbent running for re-election, the Republicans don’t do much better than when they run against Democratic incumbents.

It is always possible that the voters want divided government. Perhaps they wish to ensure that one party is able to check the other; or they may like Republican positions on “presidential issues” (for example, the economy or foreign policy) and Democratic positions on “congressional issues” (for example, the distribution of government services and benefits to the people). Morris Fiorina of Harvard and Gary Jacobson of the University of California, San Diego, have adduced some ingenious (though indirect) statistical evidence for each of these possibilities, but their findings are open to the obvious objection that it is hard to find any real, living voter who seems to be in favor of divided government. Quite the contrary: most voters complain of government gridlock and partisan bickering.

Now come two of this country’s ablest political reporters to offer some new answers to these puzzles. E. J. Dionne Jr., formerly of The New York Times and now of The Washington Post, argues that Americans hate politics because the political elites—the chattering classes, as Anthony King calls them—have increasingly redefined politics in ideological terms that most voters find irrelevant to their real problems. There is a silent majority, says Dionne, but it is not the one that conservatives talk about. It is a centrist silent majority that is in agreement as to what this nation’s real problems are, and possibly even in agreement as to what the solutions might be. Ideological politics, practiced by liberal and conservative activists, prevents this consensus from expressing itself in policy. The people, eager for real choices, are given false choices; anxious about the economy, the family, the school system, and crime, they are confronted by candidates intent on arguing over abortion, gun control, supply-side economics, and the Pledge of Allegiance. And so the people respond by turning their backs on the candidates and, alas, on the system.

ALAN EHRENHALT, for many years the political editor of Congressional Quarterly and now the editor of Governing magazine, suggests that divided government is not the result of gerrymandering, incumbent advantage, or voter preference, but of the kinds of people willing to offer credible campaigns for legislative posts. He notes that divided government is not unique to Washington, that it is characteristic of many states as well. The sight of Republican governors confronting Democratic state legislatures has become almost as commonplace as that of Republican presidents facing Democratic Congresses.

Ehrenhalt argues that this cannot be understood by looking simply at what voters demand. We must also consider what politicians supply. And what they have supplied, increasingly since the 1960s, has been a cadre of liberal Democrats eager for careers in elective office and skilled at mobilizing the most sophisticated and exhausting campaign tactics to win those offices. Ehrenhalt may well become known as the father of supply-side political science.

To make his case, he goes back to the grass roots and provides us with vivid portrayals of street-level politics in four cities (Concord, California; Sioux Falls, Iowa; Greenville, South Carolina; and Utica, New York) and four state legislatures (Wisconsin, Connecticut, Alabama, and Colorado). In each place, Ehrenhalt finds old-style politics as practiced by citizen legislators and party-oriented professionals giving way to new-style politics as practiced by full-time professionals, loyal not to parties or structures, but to themselves and their ideologies.

In some places it began with reformers replacing party bosses, as in Utica, Greenville, and the Connecticut legislature, but it did not stop there; and in many places it never began there. There were no party bosses to be ousted from the state legislatures of Wisconsin or Colorado. There were, instead, farmers, merchants, and insurance agents who viewed politics as a useful avocation and government as a limited institution. Being in the legislature might be good for business or for the ego, but the job didn’t pay much. Since only a few people could afford to be in office, not many credible candidates ran for office. Elections were often settled by folksy, friends-and-neighbors appeals reinforced by endorsements from small-town newspapers and people in the chamber of commerce.

NO MORE. State legislatures increasingly meet year-round, pay their members a decent wage, and provide them with a sizable staff. People not only can make a career out of local politics, they must make a career out of it: the demands on those who are elected, and the intense competition among those who seek election, has put politics beyond the reach of people who view it as a hobby.

Ehrenhalt argues that the people prepared to make even local politics a vocation rather than an avocation have been, since the 1960s, disproportionately liberal Democrats. As one Wisconsin state legislator told him, “The Republicans hate government. Why be here if you hate government? So they let us [liberal Democrats] run it for them.” Or as another legislator put it, “There are some Republicans in my district who could run against me and make my life miserable. But the Republicans can’t come up with candidates who will put in hundred-hour weeks. So they don’t make it.”

In this way Ehrenhalt explains an otherwise puzzling phenomenon: communities that vote regularly and heavily for Republican candidates for president and that once elected Republicans to their city councils and state legislatures now choose for these local offices liberal Democrats. The Democrats outhustle and outperform their Republican rivals: they are more energetic and sophisticated campaigners, and they deliver on bread-and-butter, neighborhood issues.

Once in office, moreover, they have a good deal of freedom to pursue a liberal political agenda, because voters are ignorant of, or indifferent to, efforts to enact comparable worth statutes or gay rights ordinances and are happy to have more environmental legislation, especially if it can be presented as part of a slow-growth plan. Sometimes the liberals overreach themselves, of course, and there is a backlash. Still, at the local level, as at the national level, voters tolerate a fairly wide range of legislative discretion, provided only that the legislators avoid scandal and respect the preferences of the people who voted for them on a few gut issues.

Supply-side politics, like supply-side economics, has a price: a political system that is open only to individual careerists who build personal followings is a system that will be lacking in any mechanisms to screen candidates, to build coalitions, or to hold leaders accountable. Power and leadership have been heavily diluted or have simply evaporated. Ehrenhalt is not in the grip of any romantic attachment to a golden age of machine politics, but he is surely right to ask this question: “Why is machine government a greater affront to democracy than a government of leaderless individualists prone to petty rivalry and endless bickering?” The people like politicians who are not beholden to anybody; but a politician who does not owe anybody a thing also does not have many tools with which to govern. Obligation is a two-way process: what I owe to an organization or leader (because it helped elect me) is also a claim I have on that organization and leader (because it must help me govern).

THIS SUGGESTS A link between Dionne’s argument about ideological politics and Ehrenhalt’s argument about careerist politics. Divided government need not lead to deadlocked government, and often it has not. Either mediating institutions will negotiate a settlement between the executive and legislative branches (as strong Democratic congressional leaders did in the Eisenhower administration, or as even stronger party leaders once did in Connecticut government) or politics will be driven by powerful ideas that sweep both branches before them (as happened with respect to tax reform and environmentalism).

But divided government in an era of individual careerists who are constantly running for re-election, and who are motivated to some significant degree by either personal ideology or the need to satisfy ideological elites who control campaign funds and party caucuses, is another matter. The legislative workload will increase as individual policy entrepreneurs attempt to advance their personal agendas and to take control of issues. Mediating institutions will lose influence, and collegiality will suffer. Political activists will become more deeply polarized as they watch government bend to the pressures of their ideological opponents. Citizens will watch the hubbub with growing dismay.

It is hard to imagine what, if anything, can be done about this. Setting maximum terms for legislators may increase the turnover among officeholders, but it will not change the kind of institution in which they operate or the processes by which they win elections. Ehrenhalt finds it impossible to justify on a rational basis the system that we now have, but he offers no alternatives to it.

DIONNE DOES OFFER an alternative of sorts: an appeal to liberals and conservatives to alter the terms of public debate so that politics once again has something to do with what the public feels really matters. Only if ideological activists redirect politics away from symbolic issues can we avoid, in his opinion, a repetition of the presidential campaign of 1988, in which what passed for public debate centered on Willie Horton, the Pledge of Allegiance, and membership in the American Civil Liberties Union.

Many of Dionne’s criticisms of liberalism and conservatism are telling. Liberalism became the province of upper-middle-class intellectuals and radicals who professed a desire to help ordinary citizens, but held in barely concealed contempt the most cherished values of those people—patriotism, religious conviction, and traditional sexual morality—and dismissed as misguided their central concerns—rising crime rates, deteriorating public schools, and foreign competition for local markets. Though the New Left was founded out of a desire to encourage participation, to decentralize decisions, and to expand opportunity, the left generally came to espouse programs that limited participation to those who could afford lawyers, that required more centralized decision-making by the federal government, and that limited equality of opportunity in the name of programs (goals, quotas, “diversity”) that reflected a desire for equality of result.

Conservative intellectuals seized upon these liberal mistakes and laid the groundwork for a reassertion of conservative policies (tax cuts, market strategies, military strength) in the 1980s. But conservatism was better as a source of opposition to government than as a guide to it. The movement was an uneasy coalition of cultural conservatives who accepted government and were willing in some ways to see its powers enlarged, libertarians who opposed all government save the most minimal, supply-side economists who wanted tax cuts, and anti-Communists who wished to see the United States pursue an aggressive policy against the Soviet Union and its proxies even if it cost money. When Reagan took office, there was so much to do that most conservatives could agree that the internecine conflicts be subordinated. Taxes were cut, the military was strengthened, and the demand for new regulations was resisted. In time, however, the conflicts surfaced, and conservative politicians had to choose between competing conservative policies—between a balanced budget, lower taxes, and a strong defense.

Just as liberals had been unable to reconcile their desires with popular values and bureaucratic capacities, conservatives were unable to reconcile theirs with popular preferences and democratic requirements. The American people do not like liberal politicians, but they like liberal policies—federal spending on education, transportation, health, and the environment. In almost any election, the advantage will lie with whichever candidate promises to do more about these concerns.

Dionne’s analysis is perceptive and evenhanded, but when it comes time for remedies he offers few persuasive alternatives to the positions now taken by rival political elites, and no mechanism whereby the influence of those elites on the selection of candidates or the promotion of policies can be reduced. Dionne joins the many voices calling for a revival of the “civic interest” or “civic virtue,” by which he means that individual interest must be tempered by communal responsibilities. He illustrates that perspective by his suggestion that the deep public concern about schooling, housing, and economic growth might be met in ways that liberals and conservatives can both applaud, if the government employs strategies (vouchers, housing supplements, and enterprise zones) that empower individuals, decentralize decision-making, and create incentives. By the same token, the plight of the poor (a liberal concern) and the need for self-reliance (a conservative concern) can be fused by linking welfare to a work requirement. In these respects, Dionne aligns himself with Republicans such as Jack Kemp and Jim Pinkerton and with Democrats such as William Galston, Christopher Jencks, and Robert Shapiro. (I agree with much of this.) With them, he believes that there is a popular center in American politics that can be reached and built upon if activists stop basing their appeals on what fellow activists will reward.

Perhaps. But it must trouble Dionne that few of his intellectual allies wield much influence in either party, at least with respect to what counts—nominating candidates and shaping legislation. For many years Democratic and Republican candidates for president have had to pass certain litmus tests (say, on abortion and taxes) that significantly narrow the range of viable candidates. In debating policies on the issues that trouble people the most—crime, race, schooling, drugs—the significant interest groups remain, as they have long been, ideologically polarized activists whose ability to raise a budget and to mobilize volunteers seems directly proportional to how dramatically they can portray the “threat” and how stridently they can denounce their opponents. Dionne must hope that the Progressive Policy Institute, the Democratic Leadership Conference, and the Kemp wing of the Republican Party can somehow become a match for the ACLU, the National Rifle Association, the Children’s Defense Fund, and the National Education Association; but he gives us little reason to share his hope.

LET ME OFFER a slightly different explanation for the decline in popular confidence in government, an explanation that Dionne himself suggests toward the end of his book. People give up on government when government announces that it will solve an important problem and then fails. Before the 1960s the federal government played almost no role in abortion, education, crime control, race relations, or health care. The few things the government did, it did very well. It ended (by the accident of World War II) the Depression, it won a popular war, it built the interstate highway system, and it provided retirement benefits for the elderly. Small wonder that Americans took pride in their government in the 1940s and 1950s.

But improving race relations, regulating abortions, reducing crime, and delivering good health care at a reasonable price are far more difficult tasks, especially because some of these were created by judges unconcerned about the impact of their decisions on public support for government. Once the government was embarked on them, failures, shortcomings, and frustrations were inevitable. Special-interest groups proliferated as the government took on more tasks, and they contributed to rigidities, complexities, and delays in the management of those tasks. Ideological elites who once argued over whether the government should do something at all now argued over how it should be done. And the intellectual skills that stood them in good stead in debating the need for a course of action stood them in poor stead in discussing the practical details of that course of action. (To make matters worse, the government in 1963 failed to do one very important thing: keep its president from being murdered.)

Dionne’s argument, then, can be stood on its head. It is not that liberals and conservatives have disgusted the public by framing political issues as a series of false, ideologically extreme choices. It is that government, having embarked on policies that inevitably raise the most profound philosophical issues, has necessarily called forth an intense ideological debate over the ends sought and the means deployed.

AMERICANS STILL HAVE more confidence in their leaders than is the case with the peoples of almost any other democratic nation. The bewildering, personalistic, and adversarial quality of American politics is different, of course, from what is found in much of Europe, a fact that reflects the combined impact of mass higher education (which has supplied us with a much larger chattering class), a weak party system (which has made politics so entrepreneurial), and the separation of powers (which has provided so many opportunities for interest-group participation). Still, Americans have shifted toward a more European view, which is to say, a more cynical view, of such matters. We are less optimistic and less trusting than we once were. And rightly so: if Washington says that we should trust it to educate our children, to protect our environment, and to regulate our economy, we would be foolish not to be cautious and skeptical.

If history is any guide, Americans will take pride in their government not when people with advanced degrees start writing more moderate articles or when the Democrats figure out how to nominate a centrist candidate for president, but when the government takes on an important job and does it right. Operation Desert Storm is a powerful example:when it succeeded, the chatterers were either struck dumb or disproved by events, and the ideological debates over the size and purpose of the military were shoved aside.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of tasks that no one, least of all the government, knows how to do right. Still, there are some tasks that are in principle amenable to concerted action. Suppose the government were to say, “We don’t care what it takes, we’re going to get the homeless off the streets by providing institutional care for some, housing others, and jailing still others. It is a disgrace that they are there when it is totally unnecessary. General Schwarzkopf, or someone like him, will be put in charge.” Various elites, from left to right, would go into a snit; but if it worked, and worked without doing any serious injustices, the people would gratefully say that “it’s about time.”

Or gang shootings in poor neighborhoods: we do know, after all, how to disarm people. We did it with tens of thousands of Iraqi POWs, and we do it everyday at American airports. It does not require waiting periods to buy guns (which I favor, but without much optimism), harassing gun dealers, or complicated registration forms. It requires that neighborhoods or housing projects that are now free-fire zones be converted into no-fire zones. You establish a perimeter around the area and you refuse to let anyone enter or leave or move about in it who is carrying a weapon without a lawful permit. The searches can be non-intrusive (they can be electronic); and the guns can be “arrested” without even arresting the people. The ACLU and the NRA would find common cause at last, united in opposition to this. But if it worked, even in a few places, the people would say that “it’s about time.”

THERE ARE MANY things that are uncertain or even just plain wrong with these proposals. Yet consider the alternative: to restore popular faith in government by re-educating college graduates, persuading people to abandon or moderate deeply held convictions, talking congressmen into becoming more deliberative and collegial, inducing Republicans to share the Democrats’ enthusiasm for full-time political careers, taking abortion off the public agenda, and making blacks and whites trust each other.

Dionne makes my point without my examples. “To restore popular faith in the possibilities of government,” he writes, “government must be shown to work.” That means reducing the stifling array of constraints that prevent anybody from doing anything. For we have brought to perfection a political process that can always say “no” at the expense of one that can ever say “yes.” Dionne’s history of the ideological wars reminds us of where those constraints came from, and Ehrenhalt’s account of political recruitment shows us why elected officials have incentives to multiply those constraints. The next book we need—and need badly—is one that tells us in some detail how to get out from under the crushing load of rules, set-asides, hearings, certificates, concurrences, impact studies, and procurement requirements that keeps our government big without letting it be effective.

James Q. Wilson is the Collins Professor of Management and Public Policy at UCLA and the author, most recently, of Bureaucracy (Basic Books). This article appeared in the June 3, 1991 issue of the magazine.