LOS ANGELES—Let’s see. On March 1 we have the Great Peace March. Three thousand people walking from Los Angeles to Washington for nuclear disarmament, starting at a star-studded concert in the L.A. Coliseum. Endorsed by Madonna. Tents provided by North Face. Shoe sponsorship under negotiation. Total cost: $20 million. Arrives in Washington November 15.

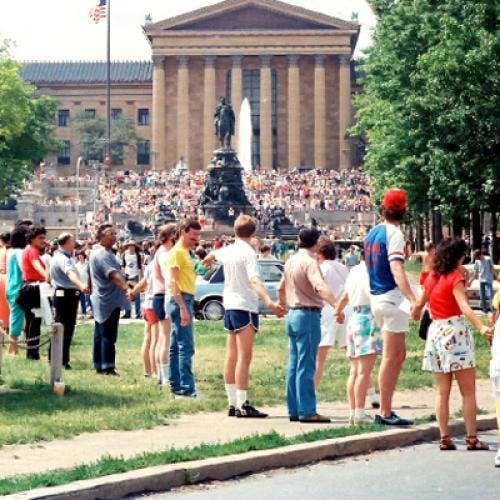

Meanwhile, on May 25, there’s Hands Across America. A 4,000-mile human chain from Los Angeles to New York to raise $100 million to “combat domestic hunger and homelessness.” Organized by USA for Africa (“We Are the World”). Chief corporate sponsor: Coca-Cola. Computers by Compaq. Five million to ten million participants, including “the largest number of celebrities ever assembled.” Ten dollars for a place in line, $25 for a commemorative T-shirt.

Did I mention that May 25 is also the date of the “Freedom Festival,” a star-studded concert “huge in its scope” designed “to salute America, its music, and its heroes” and to raise money for Vietnam veterans, according to celebrity sponsor Don Johnson of “Miami Vice”?

It’s getting pretty crowded out there, what with all the monumental affirmations of the American spirit. The looming prospect of compassion gridlock on May 25 was only partially alleviated when the hand-holders spurned the peace marchers’ offer of help and “went south,” choosing a route that will put some 360 miles between them. The Great March is currently scheduled to be somewhere between Denver and North Platte when the Great Chain steams through Albuquerque, Amarillo, and Little Rock.

True, these coming events are only the latest in a long line of attempts to harness the power of “Entertainment Tonight” and the corporate tax deduction for worth causes. But they are the most grandiose and the most political. Except that politics isn’t really the right word. What we have here is really the birth of a new form of social activism. Not politics, but Celebritics. In politics, movie and pop stars are just one asset a candidate can throw into the fray. Celebritics is when the celebrities become so powerful that they frame the issues and run the campaigns themselves, dispensing with the boring old politicians altogether.

Celebretics represents the flowering and cross-pollination of two phenomena. The first is the susceptibility of Americans to vague demonstrations of pride under corporate sponsorship. The breakthrough event here was probably the AT&T Olympic Torch Relay. Now hosts of would-be Peter Ueberroths are organizing similar logo-laden feel-good campaigns, from the refurbishing of the Statue of Liberty to the outfitting of the America’s Cup contender. The second phenomenon was the success of Band Aid, Live Aid, Fashion Aid, “We Are the World,” Comic Relief, and Farm Aid at raising money and capturing public attention for causes with strong political overtones. This spring’s mega-events combine such celebrity fund-raising with torch-relay style stunts, in the name of causes once deemed very political indeed.

IN BOTH EVENTS, however, politicians are considered expendable, even disreputable, while celebrities are essential. The peace march is the work of a group called PRO-Peace, led by David Mixner, a jolly, left-oriented peace activist and veteran of the civil rights, antiwar, and gay rights movements. Mixner is frankly scornful of the “18th-century” rate of progress the politicians have made toward disarmament. His goal is to change politics from the outside, to shift the political demand curve dramatically and then sit back and watch the politicians scramble to adjust. His device—a march—is right out of the standard grass-roots activist handbook. But mere grass-roots activism could not finance a moving city of 5,000, including six mobile kitchens, 2,500 tents, a mobile bank, stage, meeting halls, and post office for a 255-day trek.

Celebritics can finance it, at least in Los Angeles, the capital city of Celebritics, where the most amazing sums of money are available for the least concrete causes if the mood and lighting are right. Mixner’s first big event, the filming of a video “pre-enactment” of the march, depended heavily on the lure of stars. “More than 50 celebrities,” boasted a PRO-Peace publicist—invoking the new quantitative measure of success—including Madonna (a major coup), Rosanna Arquette, and virtually the entire Brat Pack. Celebrity events have already helped Mixner raise almost four million dollars, enough to provide PRO-Peace with a full-time staff of 113 paid workers, more than a decent-size presidential campaign. I have been to the sprawling PRO-Peace offices and can verify the existence of many busy-looking people, maps, diagrams, scouting reports, and computers.

On the Great March itself, stars will be flown or trucked in as part of a “Celebrity Relay.” It will be “like one continuous celebrity walking across the country,” says PRO-Peace media coordinator Peter Kleiner. Mixner points out that Martin Luther King Jr.’s Selma-to-Montgomery march also featured bus-loads of celebrities—Peter Lawford, Shirley MacLaine, etc.—and roadside shows by Peter, Paul and Mary. But King’s march, and the antiwar marches of the sixties, would have happened without celebrities. Mixner’s would not.

That is even more obviously true of Hands Across America. If the offices of PRO-Peace exude an earnest idealism, the recent press conference for “Hands” was pure self-congratulatory glizt. Held at the pretentious Le Bel Age hotel in West Hollywood, with valet parking for reporters, the conference featured no politicians, but “an incredible number of celebrities,” according to “Hands” promoter Ken Kragen. Starlets abounded, and the emaciation required by their profession (Susan Anton looked as though she could eat a horse) plus the lavish buffet awaiting the briefing’s end gave its anti-starvation theme a piquant relevance. An “ABC Evening News” segment on poverty was shown, like a precious bit of reality in this unreal setting. Kragen, personal manger of singers Kenny Rogers and Lionel Richie, then appeared in a bright red velvet sports coat to announce that Prince had “bought” the first mile. Rogers read a telegram from Bill Cosby (“Helping out is cool”). An NBC executive announced the gift of free time on the Super Bowl telecast. Press releases listed 408 entertainment industry endorsements. When they played the “Hands Across America” theme and everybody joined hands you could have snorted the self-satisfaction with a spoon.

CAN KRAGEN pull it off? A certain skepticism recommends itself—i.e., whoever thought of the idea has never driven across Texas. In Arizona and New Mexico, “Hands” must convince 1,128,400 people to string themselves along the hot tarmac at exactly 3 p.m. (EDT). That’s two of every three human beings living anywhere near the route. They are also to be made to pay ten dollars for the privilege, although line-crashers will presumably not be forcibly ejected by armed Kragen police. The precision logistics required for “Celebrity Coordination” alone are an advance man’s equivalent of orchestrating a first-strike nuclear attack, and the man whose firm Kragen hired—at $80,000 for ten months’ work—to put it all together, a middle-tier Carter operative named Fred Droz, does not have the paper credentials that would bowl over anyone in Washington.

But I would never underestimate the power of celebrity in today’s America. People thought Ueberroth would never get it done either, a personal comparison Kragen is fond of drawing. Simon and Schuster is negotiation for book rights, and the networks seem to be going along. Not to mention “all the heritage, power, and emotion of the Coca-Cola system.” Kragen could fail to achieve his goal of a coast-to-coast chorus line and still be a success, hogging the news (these events are made to order for Dan Rather) and raising tens of millions of dollars.

Face it, Washington. While politics on K Street slowly congeals around the sensible center, with Reagan praising Social Security and Democrats studying workfare—I mean, Chuck Robb vs. George Bush, there’s an echo not a choice—what is going to fill the emotional void that clashing ideologies used to fill? Show biz, that’s what. Do you think America would rather sit around mubling about Gramm-Rudman-Hollings or hold hands vicariously with Rosanna Arquette? Now is a good time to ponder the meaning of this question for the Republic.

I am not saying nuclear disarmament and fighting poverty should be left to experts and NEW REPUBLIC writers or that the government has a monopoly on compassion. But even if you agree with the goals of these two particular examples of Celebritics (as I do), there are at least two good reasons to worry about the trend.

The first concerns its potential to distort reality. Politicians are not a group known for their candor, but they are sodium pentothal addicts compared with Hollywood agents and PR men, who inhabit a world where the Big Lie is the norm and the truth a minor annoyance to be handled like an overeager fan. At Kragen’s press conference a thick “information packet” was handed out to virtually everyone who wanted it—except reporters. When I asked for a copy, a tight-lipped publicist assured me: “You will be given all the information you need….”

Kragen has skillfully used the PR trick of drawing the spoon-fed entertainment industry press (which has a natural interest in having a big event to cover) into the conspiracy to manage the news. This may be “the largest interactive event in the history of mankind,” but Kragen reminded the press not to give it too much hype too soon. Kragen’s trump card is a direct appeal to reporters’ consciences. Journalists who watned to write about his efforts to hit up TV networks for airtime for “We Are the World” were reminded they might hurt the cause of starving African babies. At the “Hands” briefing, reporters were made to feel like party-poopers if they declined to join hands during the emotional theme-playing. You don’t have to be a doctrinaire adversary journalist to see the potential here for mutual deception. It’s no great crime of Hands Across America says it’s funding a study to “go to every one of” 150 “hunger countries,” even if the truth is that researchers will only actually visit as few as ten percent of them. But HAA will quickly become as wasteful as HHS if reporters are discouraged from pointing these things out.

A SECOND CONCERN is more substantive. Celebritics requires emotional, universal, and non-“political” ends: starving Africans, “hungry and homeless Americans,” or “the single goal of ridding the world of nuclear weapons” (an aim amorphous enough to have now been endorsed by both Reagan and Gorbachev). Anything more specific, and it might be hard to sign up Coca-Cola, and Morgan Fairchild’s agent might have second thoughts.

Mixner promises to back up his abstract peace them with pointed issues papers (attacking Star Wars, supporting a test ban), which may be why he seems to be having more trouble than Kragen closing deals with corporate sponsors. Kragen wants to have it both ways. He appeals for aid as a basic, uncontroversial human response to the immediate need of starvation. But his ambitions extend well beyond simply feeding a lot of hungry people. Fifty-five percent of USA for Africa’s money (some $25 million) is not being used to feed today’s starving Africans. It is sitting in the bank waiting to be spent on “Recovery and long-term development projects” in eight African nations. Kragen’s domestic “grants” have followed an even more lopsided pattern. Aside from $10,000 or so distributed over Christmas, none of the $500,000 spent so far has gone to actually feed or house poor people. Instead USA for Africa has funded three projects to find “long term solutions to the problems of hunger and homelessness.” If people want to give Kragen money to set up his own Ford Foundation, fine. But when USA for Africa abandons the Salvation Army business and enters the long-term social reform business, it will have to answer the same tricky questions confronted by the others who have trod this path before. How to bolster incomes without encouraging dependency? How to instill hope, patience, and discipline in a despairing and often antisocial underclass? Or the group’s grants so far, the largest went to Cities in Scools, which attempts to coordinate existing social services for troubled students. USA for Africa touts this as an example of its “innovative” “venture capital projects.” But Cities in Schools is hardly a new program. Its president, William Milliken, is a veteran antipoverty salesman who hustled millions from Jimmy Carter and more recently hustled $800,000 from Ed Meese. Asked about the exact nature of the “pilot projects” Kragen’s group is financing, Milliken says: “We just have done this on the phone. We need to talk again on the specifics of it.”

Cities in Schools may be a great thing. It may be a social-work band-aid doomed to insignificance But that’s a political judgment, and I’d rather have it made by a politician who recognizes that it’s a political judgment, whose political biases I know and agree with, and whom I can vote out of office, than by well-meaning celebrities whose political views, if any, lie obscured under a thick layer of vague, press-agent compassion. Sorry, Prince.

Politicians have another virtue. Only the governments they run have enough resources to “end hunger.” The $100 million Kragen hopes to raise is about eight-tenths of one percent of the budget of the food stamp program. Kragen admits the money generated by Hands Across Ammerica “will only make a dent in the overall problem.” He says the issue is “not just dollars” but public awareness, and alludes to a possible “impact on legislation.” What legislation? More money for food stamps? But aren’t jobs preferable to a more generous dole? There’s a reason why politicians debate those questions. Kragen could stack singing celebrities 4,000 miles into space and he won’t have helped resolve them.

The delusion of Celebritics is that our problems reflect mainly a failure of will on the part of our elected leaders. The politicians have screwed up. They haven’t ended hunger. They haven’t removed the threat of Armageddon. What’s wrong with them, anyway? Time for the celebrities and their fans to take over and supply the missing humanitarian willpower. There’s some truth here. (Reagan’s will to negotiate an arms treaty may need a little bolstering.) But warm, compassionate feelings and cold, hard cash are not enough. Progress requires choices, political ones. By avoiding and concealing these choices, Celebritics sets us up for a big fail when all the televised and merchandised outpourings of Hollywood goodwill fail to produce “solutions” to match the ratings.

“This is not about any politics,” Hand Across America Actors’ Committee co-chair Dyan Cannon declared at Le Bel Age. “This does not have anybody running for office. This doesn’t have any of those labels on it. It has nothing but love to it.” That’s the trouble.

This article appeared in the February 24, 1986 issue of the magazine.