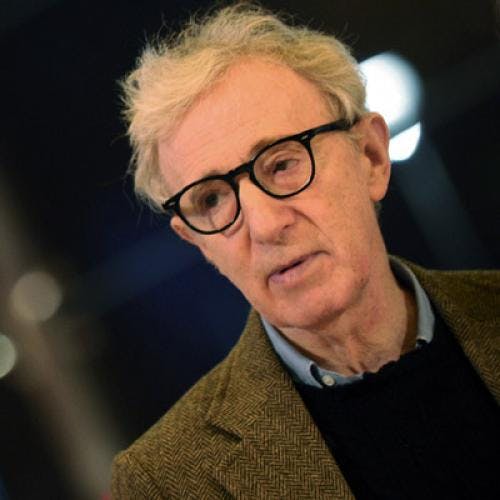

Now that a New York judge has mercifully told Woody Allen and Mia Farrow to put a cork in it, one may seize the blessed silence to ask why so many people are upset and enraged by this story. I mean upset and enraged at more than Woody's appalling behavior with his ex-girlfriend's adoptive Korean daughter, Soon-Yi.

I think it has to do in part with people being angry at themselves for having assumed that the Woody of the movies was the same as Woody off-screen, the Woody of Elaine's, the clarinet, and the Knicks games. The point has been made that Woody deliberately blurred his private and cinematic personas. But I doubt if people realized how sore they would become once the difference between the two was exposed.

Charlie Chaplin also blurred his fictional character with his own. And since Chaplin was caught in a similar mess — in his case with a 16-year-old (Lita Grey) whom he got pregnant and was ordered to marry — I'd like to use Chaplin to try to explain the anger at Woody.

Both Woody and Chaplin bought their troubles by creating fictional characters of whom audiences had definite expectations. When the artists violated those expectations with their real lives, their audiences were especially appalled because both men had been using their characters to imply, "Love him, love me." As long as people felt that creator and creation were acting the same part, who could turn the boys down?

Yet the love one felt for the Chaplin tramp was a lot more admiring than that extended Woody's New York Jewish neurotic. Think of the tramp in City Lights. Here was a near-perfect human being — self-sacrificing, generous, humane, steadfast, in the end, heartbreaking. His total admirability was made palatable by the fact that he was down-and-out and funny; otherwise he would have glowed like a god. Indeed, Chaplin may have created the feet, the smudges, the outfit to make his god less blinding.

Woody's Woody is no such thing. His obsession with success (Annie Hall), his hypochondria (Hannah and Her Sisters), his envy (Crimes and Misdemeanors), his barely submerged lechery (everywhere) make him, at very best, a figure in whom one recognizes the extremes of one's own irritating features. He may be lovable for that, but it is a nerve-wracking kind of love, engendering forgiveness over passion. One reason, I think, the public has chosen to know Woody as "Woody" rather than "Allen" is that the name makes him more lovable than he is. Chaplin needed no such extra boost.

There are two things both fictional characters have in common, though. They are men of principle, and they have a hell of a time getting the girl. When these two elements collided with the real lives of Woody and Chaplin, ka-boom. In real life neither Woody nor Chaplin had the slightest trouble getting the girl — Woody's Louise Lasser, Diane Keaton, and Mia; Chaplin's Paulette Goddard, Pola Negri, Marion Davies, and a bevy more. As for being men of principle, that notion collapsed when the girls they got were girls.

While Woody's character is less lovable than Chaplin's, he is more interesting when it comes to this movie-life collision because one identifies more closely with him. Woody, as noted, intentionally created a neurotic who misbehaves. This kind of person is often called a romantic, and the Woody figure is certainly that. It was romanticism that rescued him from the audience's horror and contempt in Manhattan — the movie often cited for its parallel to Woody's present mess. In Manhattan, Woody's Woody has a love affair with a high school girl (Mariel Hemingway). But the romanticism in Manhattan was the audience's as much as the character's. What Woody got people to think as they watched Manhattan was: "Well, if the girl is as serene and grown-up as Mariel Hemingway and she teaches Woody about the meaning of love, I guess it's O.K." Only in the movies is a middle-aged whiner fooling around with a girl "who still does homework" O.K.

In short, what Woody has done in his movies is to make people suspend or bury moral judgment by playing on the assumption that as crazy as Woody's Woody could get, he would never get that crazy. A high school senior? O.K. But never his girlfriend's daughter! He wouldn't. Would he? To give the real Woody a kind of credit, it was not he who said "never," it was the public, which put itself in the character's skin. Woody, via art, merely made the barely tolerable colorful. At worst he made misdemeanors of crimes.

He did this not simply by raiding his life for his art, but by manipulating his life in his art. Chaplin created a wholly superior being. Woody created only a slightly superior being, whose superiority lay solely in the ability to see himself ironically. A psychologist might view this creature as a form of therapy: In the real world Woody feels overwhelmed by his neuroses. But he can wrestle them to the ground on the screen, where they are not monstrous but funny, and short-lived.

Or the manipulation may be more calculated. After his early straight comedies Woody hit upon a character, the Powerful Nebbish, in whom neuroses are made normal. Audiences laugh out of a sense of relief: he's O.K. I'm O.K. And there are so many genuine villains and crazies planted in Woody's movies that the mere neurotic is O.K., heroic even.

The calculation here may be that Woody knows that people like to see their own lives as art. In art everything is not only forgivable but beautiful. Who, sunk in his despair, would not like to be able to step away from reality and behold himself as a player in the human comedy? The identification thus is not only with Woody's Woody, but with the man himself, who has brilliantly manufactured a life-in-art, a way out, a movie.

Woody has created this complicated soup, and the audience has found it delicious, at least until lately, because whatever else may be said of him, Woody has genius. Do not for a moment think that Woody could not rebound from his current jam and make a Manhattan sequel in which Mia is portrayed as the shrewish ex-non-wife and Woody winds up cheered as the best thing to happen to Korea since Truman.

I wonder if Woody sees that he has crossed the line, that he ought to have kept his life closer to his art. Or maybe he thinks life really is a movie, or worse, a stand-up. At his press conference it was embarrassing enough to hear the enemy of cant speak of his new "positive" relationship, but then to hear him characterize his remarks as "straight lines" seemed to show that Woody hasn't the slightest idea where he is playing these days.

This article appeared in the September 21, 1992 issue of the magazine.