Gun control is one of the great pieces of unfinished business for the Democratic Party. Although the party has never been unified in its support of restrictive gun laws—indeed, gun control historically transcends the usual party lines—for the past century Democrats have pushed for a more vigorous role for government in regulating guns. They’ve been largely unsuccessful, however, and lately Democrats have made Avoid Gun Control an informal plank in the party’s platform.

The Newtown massacre however may have changed all that.

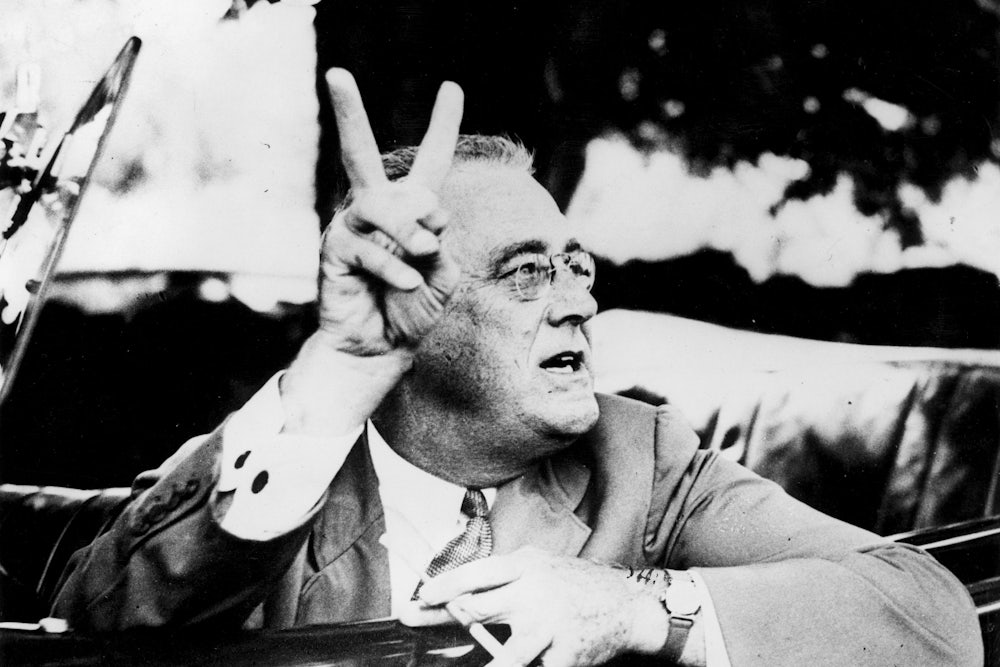

Like health care, social security, and so many other issues central to the Democratic agenda, the party’s support for gun control stems from Franklin D. Roosevelt. For most of American history, regulation of guns was a matter of state law. State-level regulation, however, came under tremendous pressure during the 1920s and 30s, when Prohibition-era gangsters like Al Capone overwhelmed local police resources and traveling desperadoes like Bonnie and Clyde easily escaped capture by racing across state lines. FDR promoted a “New Deal for Crime,” which, like his other New Deal policies, involved expanding the role of the federal government in serving the people.

Roosevelt’s original proposal for what would become the National Firearms Act of 1934, the first federal gun control law, sought to tax all firearms and establish a national registry of guns. When gun owners objected, Congress scaled down FDR’s proposal to allow only for a restrictive tax on machine guns and sawed-off shotguns, which were thought to be gangster weapons with no usefulness for self-defense.

Congress watered down FDR’s bill because of concerns about maintaining the right of people in rural communities, where there was little police presence, to have handguns for protection—not because of the Second Amendment. In congressional hearings into the NFA, Karl Frederick, the leader of the NRA, was called to testify. When asked if the Second Amendment imposed any limitations on what Congress could do in regulating guns, the NRA president’s reply was surprising: “I have not given it any study from that point of view.”

Democrats renewed the fight for national registration under the next president from that party who sought to expand the role of the federal government to provide security for Americans, Lyndon Johnson. As part of his “Great Society” program—and just after Democratic presidential hopeful Robert Kennedy was assassinated—LBJ sought once again to push national gun registration through Congress. This time, the NRA was firmly opposed, as were many lawmakers from the then-solid Democratic South.

Just as many southern Democrats opposed gun control, many Republicans from the west and northeast supported it. In California, Republican Governor Ronald Reagan pushed lawmakers in his state to adopt new laws making it more difficult for radicals like the Black Panthers to walk around carrying guns openly. “There’s no reason why on the street today a citizen should be carrying loaded weapons,” Reagan said at the time. Less vocal than Reagan was his fellow Californian Richard Nixon, who would be elected president later in 1968. “Guns are an abomination,” he told his speechwriter, William Safire.

Yet the NRA and gun owners were once again able to scale back the most ambitious proposals for gun control. As finally enacted, the Gun Control Act of 1968 banned the possession of firearms by felons and drug users, prohibited the import of cheap handguns known as “Saturday Night Specials,” and required licensed gun dealers to report gun sales. National gun registration was dropped. A testament to the complex partisan lineup, every member of the mostly Democratic delegation from Texas voted against the law, except one. Republican congressman George H. W. Bush voted for the law, bemoaning that “much more” should be done.

Over the next twenty years, the country underwent a historic political realignment. Conservative southern Democrats switched to the Republican Party and liberal Republicans increasingly identified as Democrats. The partisan breakdown of support for gun control was also transformed.

Cognizant of the growing strength of the emerging gun lobby, Democrats, who had long called for stricter gun control in the party platform, softened the language in 1976 to acknowledge “the right of sportsmen to possess guns for purely hunting and target-shooting purposes.” This didn’t satisfy anyone, however, especially the many gun owners who believed guns were about personal protection in an era of rising crime and decaying cities. Gun enthusiasts knew that if the right to bear arms was simply about recreational activities, it might not last long. Ever since, the Democratic Party has fumbled around trying to find language that both calls for gun control and recognizes the Second Amendment.

The NRA, now committed to a more extreme view of the Second Amendment hostile to nearly any gun control, became a key partner in the New Right coalition that lifted Reagan to the presidency. Reagan, who understood the politics of gun control in this new environment better than anyone, gave up his support for gun laws. His turnaround was so complete that even after being shot in 1981 he refused to support new restrictions on guns. Once freed from the constraints of office, he changed his tune once again, coming out in support of the Brady background check law that was named after his press secretary and enacted in 1993.

It was the Brady law and its companion, the assault weapons ban enacted in 1994, that finally scared Democrats into almost total silence on gun control. President Bill Clinton, no slouch as a political analyst, credited his support for these laws with delivering to the Republicans a majority in the House of Representatives for the first time in half a century. Democrats came to believe that even talking about gun control was a sure ticket home come Election Day.

That’s been the conventional wisdom—until Friday. After four years of ignoring gun control—or worse, from the perspective of gun control proponents, expanding gun rights—Obama finally came out with a forceful call for “meaningful action” on guns. In part, this is due to the new political calculus he faces. No longer worried about reelection and appealing to swing state voters, he’s free to take on the NRA. And it may be that after the poor November showing by the NRA, when many of its endorsed candidates lost, fear of the nation’s leading gun organization is waning.

That certainly seems the case given the reactions of other traditionally pro-gun Democrats, like Virginia Senator Mark Warner and West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, both of whom have “A” ratings from the NRA but joined Obama’s call to action. If Republican opposition to gun control begins to soften soon, we’ll once again see an important shift in the partisanship of gun control. And Democrats may find themselves one step closer to the stricter gun control regime the party’s sought for nearly a century.