Perhaps it’s the lackluster quality of recent Republican presidential nominees that is responsible for the current upsurge of interest in Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. Esteem for Ike has risen along with nostalgia for the peace and prosperity of the 1950s. Nixon has remained an intriguing figure for his dramatic highs and lows, his obvious psychological torment, and the poignant contrast between his comparative progressivism and the die-hard conservatism of the modern Republican Party. Conservatives claim, with some justification, that liberals who despised these Republican presidents when they were in office now look to them as paragons of statesmanship and moderation. The passage of time and continuing political polarization may even someday produce a wave of nostalgia for George W. Bush.

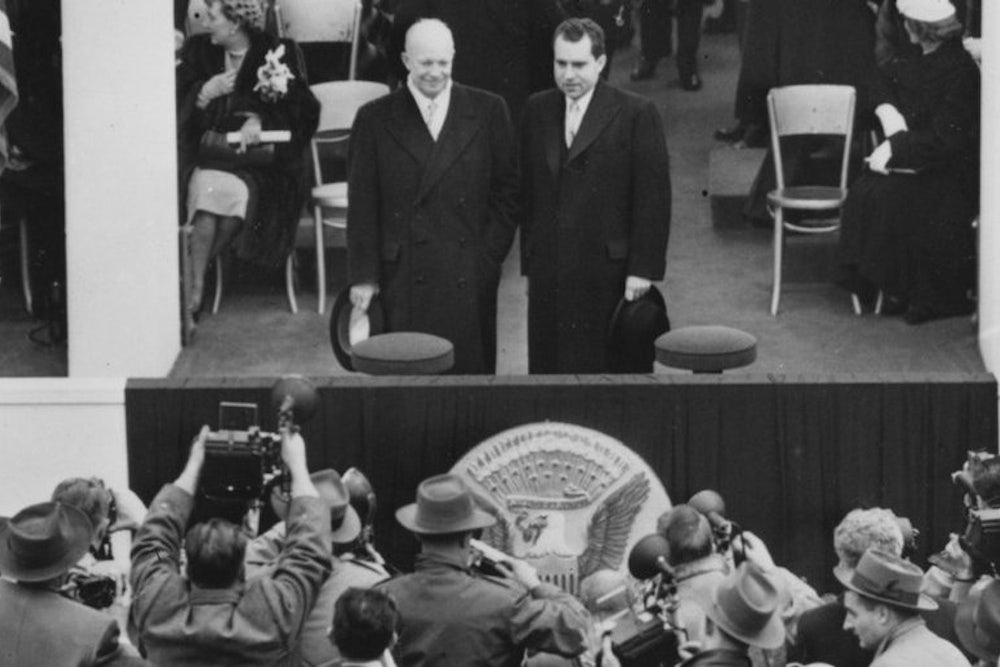

Jeffrey Frank’s Ike and Dick is not a study of either president but rather an examination of the fraught relations between them, which began at the 1952 Republican convention when party elders more or less imposed Nixon on Eisenhower as his running mate. The book purports to show how the Eisenhower-Nixon marriage of convenience “helped to shape the ideology, foreign policy, and domestic goals of the twentieth century.” That’s perhaps an overly grand ambition, given that no one has ever characterized the past century as the Age of Eisenhower and Nixon. But Frank’s approach gives the reader an inside, personal view of a tumultuous twenty-year span of history, thanks to the unusually long political association between the two protagonists.

But before we get to the merits of the book, I should admit that when it comes to presidential biographies, I’m not exactly the target audience. I doubt that most readers of Ike and Dick are going to start, as I did, by going through the endnotes to see which documents from the Eisenhower and Nixon presidential libraries he quoted and which he omitted. Nor are they likely to wonder why Frank makes no mention of the excellent writing he has published elsewhere on Nixon’s early relationship with the Los Angeles Times.1 Ultimately there’s a dangerous temptation for the specialist to review a book based on how closely it conforms to the book that he or she would have written.

With that caveat in mind, I think that the readers who come to this book out of a general interest will be pleased. The book perceptively describes Ike’s ambivalence toward his vice president and the slights and stings Nixon suffered at Ike’s hands: from the 1952 funds crisis (the catalyst for Nixon’s famous “Checkers” speech) to Eisenhower’s devastating remark, when Nixon was campaigning to succeed him, that it might take him a week to think of some idea of Nixon’s that he had adopted. Frank also describes the pair’s ongoing relationship in the years after Nixon’s 1960 loss, touching on Nixon’s failed campaign for California governor in 1962, the marriage of Nixon’s daughter Julie to Ike’s grandson David, Nixon’s redemptive triumph in the 1968 presidential election, and the final interactions between the two men before Eisenhower’s death in March 1969.

The elegant writing in this book reflects Frank’s skills as a political novelist and is several cuts above most historians’ prose.2 Both Eisenhower and Nixon appear here as three-dimensional characters, dissimilar in many ways but also sharing modest backgrounds, personal losses, and similar maternal and religious influences, which made them both idealists of a sort. Frank has a better grasp on Nixon than Eisenhower, but he is excellent at portraying what he calls the “fluctuating, unspoken level of discomfort” that persisted among these involuntary allies over their long association.

Frank has a particular talent for depicting the incidents in which Nixon seemed compelled to play the schlemiel with the elder statesman he revered: seizing Ike by the wrist when he was nominated for vice president (not knowing that the general hated to be touched by people he didn’t know), blurting out that the general had to “shit or get off the pot” in the funds crisis, and even managing to hook Ike’s jacket on a fly-fishing expedition. Frank also has a perceptive eye for character, which extends beyond the two principals to members of the supporting cast. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, for example, is described as having “noticeably bad breath,” reptilian conversational skills, and a habit of chewing on candle wax at parties.

Frank’s book is additionally worthwhile in that it goes against the grain of most recent Eisenhower biographies by making Nixon the more sympathetic figure and showing how the grandfatherly Ike could be cold, indifferent, and even cruel toward the younger man who so desperately sought his approval. Frank also highlights the extent to which Nixon was the more politically astute, better able to appreciate why the Soviets’ launch of Sputnik was a setback to American prestige and why the civil rights movement deserved federal support. He errs, however, in claiming that Eisenhower was “astonishingly naive about the business of politics,” an outdated view that has been convincingly debunked. Frank also gives short shrift to Nixon’s decades-long effort to build a national network of his supporters at the grassroots, claiming that Washington was “the only part of the country that really interested him.”

But, in the end, Frank doesn’t fulfill his stated ambition of showing how this odd couple’s interactions profoundly shaped the politics of the twentieth century. In his telling, the political events of the 1950s and ’60s are little more than plot points illuminating the relationship between Ike and Dick. There’s little to suggest that the ups and downs of that relationship had any real consequences for the nation; this could be merely a tale out of Balzac about an ambitious but troubled young man who stands to inherit his sickly old uncle’s estate. There isn’t enough substance here about Eisenhower’s fiscal approach, his combination of “New Look” atomic defense and covert operations in foreign policy, his highway program, his foot-dragging on civil rights and urban decay, his intra-party struggles with conservatives, or his worries about what he called “the military-industrial complex.”

There’s little, in short, to suggest why Eisenhower mattered, or to what extent Nixon, when he became president, thought he was fulfilling or diverging from his predecessor’s legacy. Frank also misses an opportunity to say whether Nixon, through his involvement in Watergate, justified Ike’s doubts about his character and presidential ability.

Frank does a splendid job of showing why Eisenhower and Nixon are still compelling characters, but neglects the political dimension that framed their relationship. My guess is that even general readers will want to know the significance of the political stories they’re told, no matter how beautifully those tales unfold.

See, for instance, “How We Got Richard Nixon.”

Frank deftly vivisects DC politics and society in his “Washington Trilogy” of novels: The Columnist, Bad Publicity, and Trudy Hopedale.