It seems that we have finally decided to have a moment of reckoning about drones. In Washington, hard questions are being asked about the president’s kill lists of militants in Pakistan and Yemen. In Charlottesville, Virginia, the city council recently passed the first-ever drone ban in the nation. Curious to know how the industry was coping with this heightened scrutiny, I slipped into a two-day gathering of the drone lobby—that is, the Association of Unmanned Vehicle Systems International—to find the makers of this transformative technology doing some soul-searching of their own.

We were in a characterless college auditorium in Newport News, Virginia. The attendees hailed from big players like Booz Allen Hamilton and General Dynamics along with a host of smaller contractors, and the style was military-industrial-complex casual—lots of white guys, lots of crew cuts. After perusing the free bumper stickers on offer (“MY OTHER VEHICLE IS UNMANNED”), I settled in to hear what the assembled drone makers had to say about the conference’s chosen theme: “The Reapers Come Home.”

I was expecting to catch a rare glimpse of the defense industry at its most bullish. After all, even though military demand for drones is leveling off—many of its 8,000 drones are used to assist troops in the field—the domestic potential is practically boundless, as the first speaker, Peter W. Singer of the Brookings Institution, explained at some length.1 Singer told the audience how unmanned aerial vehicles could be used to fly medical samples to remote locations, track endangered wildlife, and deliver air cargo—thus handily eliminating what he called “human side” costs.

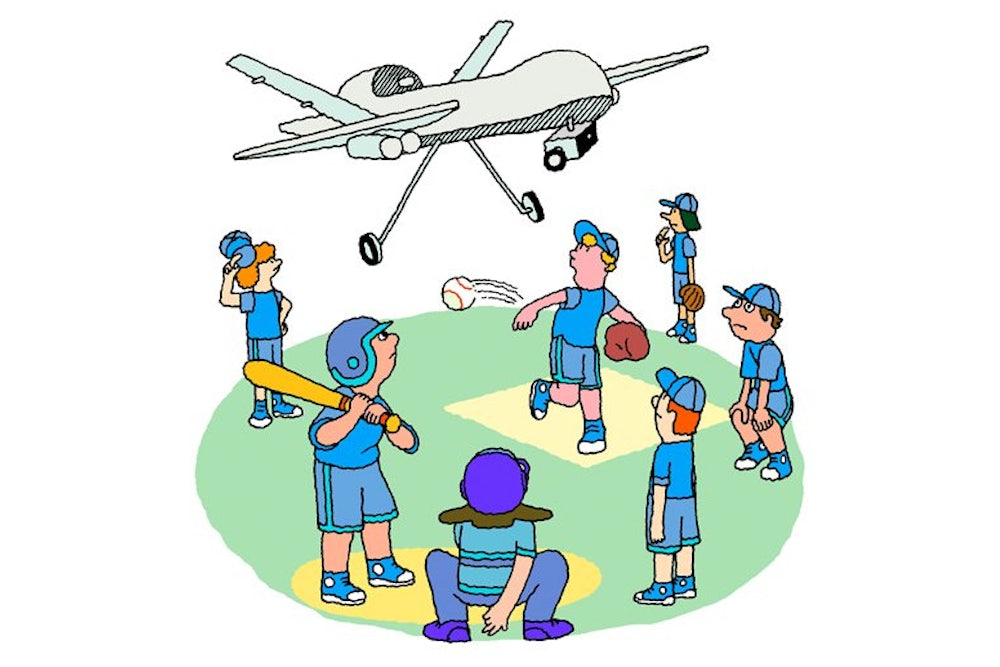

Singer also had some creative suggestions of the types of people who could really benefit from a drone in their lives, such as jealous spouses. “If the Israelis can use drones to find terrorists, certainly a husband is going to be able to track a wife who goes out at eleven o’clock at night and follow her,” he said, quoting a New York divorce lawyer. Also, soccer moms: “You’ve got the ability to take Super Bowl–like footage of your kid’s soccer game,” he said enthusiastically. “I can say, ‘Just park up over on top of the field, here’s who you’re supposed to monitor.’ ... That’s actually doable right now.”

To realize this vast potential, the Association of Unmanned Vehicle Systems International spends around $250,000 on lobbying each year and has established ties with a 60-member “drone caucus” on the Hill. Already, the Air Force trains more people to pilot drones than to fly planes. And yet it’s possible that the industry may have been too successful for its own good. Faced with the prospect of these things whizzing around in our own airspace, rather than hovering over some village in Waziristan, we appear to be on the verge of a collective freak-out. There are now countless bills making their way through Congress, state capitols, and city halls to ban or limit drones, and the Federal Aviation Administration has delayed its release of rules for their use until 2015.2 You could tell that all this hostility was getting to the drone makers. Finally, their body language said, some guys who understand.

Jason Barton leapt up from the audience to share his story. A 40-year-old Virginian with a striking resemblance to Mr. Big from “Sex and the City,” Barton got into the drone business after doing Star Wars special effects for George Lucas. A couple years ago, he met with Michigan leaders, including Senator Carl Levin and then-Governor Jennifer Granholm, to discuss expanding his company, EchoStorm, into their state. During his pitch, he mentioned that, in 2008, he’d provided video technology for a Predator sent up by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to survey the devastation caused by Hurricanes Ike and Gustav. Unfortunately, the word “Predator” meant only one thing to the pols: missiles primed to fire on Galveston. One official—Barton later told me it was Republican Representative Candice Miller—booted him out of her office. He’d spent the next few hours trying to explain that the DHS drones weren’t armed, but no dice.

Around me, his colleagues chuckled sympathetically. “I mean, are we gonna wait twenty years for a congressman [to] understand how to send an e-mail, to get to that point before they understand what the technology is capable of?” Barton demanded.

Ben Gielow, a lobbyist, played a clip that aired on Fox News last summer, claiming that the Environmental Protection Agency had sent drones to spy on ranchers in Nebraska and Iowa. Actually, they were manned Cessnas doing routine checks for clean-water violations, but the host, Megyn Kelly, launched into maximum dudgeon mode anyway. “These are the same drones we use to track down Al Qaeda terrorists,” she declared. “As you can see,” Gielow said dryly, “we have a challenge with the media.”

As the second day went on, the focus shifted to solutions. I overheard attendees muttering that maybe the safest thing to do for now was to market to farmers who wanted drones to survey their crops.3 “No one’s gonna say you’re spying on the corn,” one said darkly.

It was also agreed that the D-word had to go. “That term ‘drone’ kills us every time,” said Don Roby, a garrulous Baltimore County police captain leading a nationwide push to deploy drones for police work. Barton mentioned that, when doing business in England, he’d been urged to call drones “remote-sensing platforms.” Unfortunately, this euphemism proved to be overly euphemistic. One potential investor told Barton: “That remote-sensing platform—if it had wings, just imagine what it could do!”

Jerry Wright, a retired Air Force colonel, had another idea. When the police chief of Seattle sought approval to use drones, he brought in an ominous-looking black Draganflyer X6 to display during his presentation. City officials recoiled in horror. So, Wright said, the chief went back to the manufacturer. “They came back with the same platform painted pink and they were going to call it the Soft Kitty 2000.” To Wright, there was a clear lesson to be drawn here: “As an industry, we need more pink ones and less black ones.”

A few days later, however, the Seattle mayor barred the police from using any kind of drones, even pink drones. And when I checked in with Jason Barton, he was in despair over a siren headline on the Drudge Report accusing the Los Angeles Police Department of using unmanned aerial vehicles to search for Christopher Dorner, the fugitive ex-cop suspected in three murders. To Barton, the outrage was just another horrible misunderstanding. I asked him how we should be thinking about the prospect of drones wheeling above our heads, hunting down suspected criminals. He thought for a second and replied, “A nice safety blanket.”

For more on the domestic potential, see Time's recent cover story.

A lucky few hundred operators already have waivers from the FAA to fly drones.

Yes, this is already happening.