Sony's announcement last week of the upcoming release of its next-generation video game console, the PlayStation 4, went exactly as expected: The company's executives took the floor of Manhattan's Hammerstein Ballroom, talked about the new machine's extended RAM and redesigned controller, and left very few fans and reporters moved. Instead, whatever excitement surrounded Sony originated from a rumor that the company would finally deliver a long-awaited game called The Last Guardian. When that rumor proved untrue, Sony Worldwide Studios president Shuhei Yoshida—who probably expected to be riding high after the PS4 announcement—found himself apologizing for the game's delay.

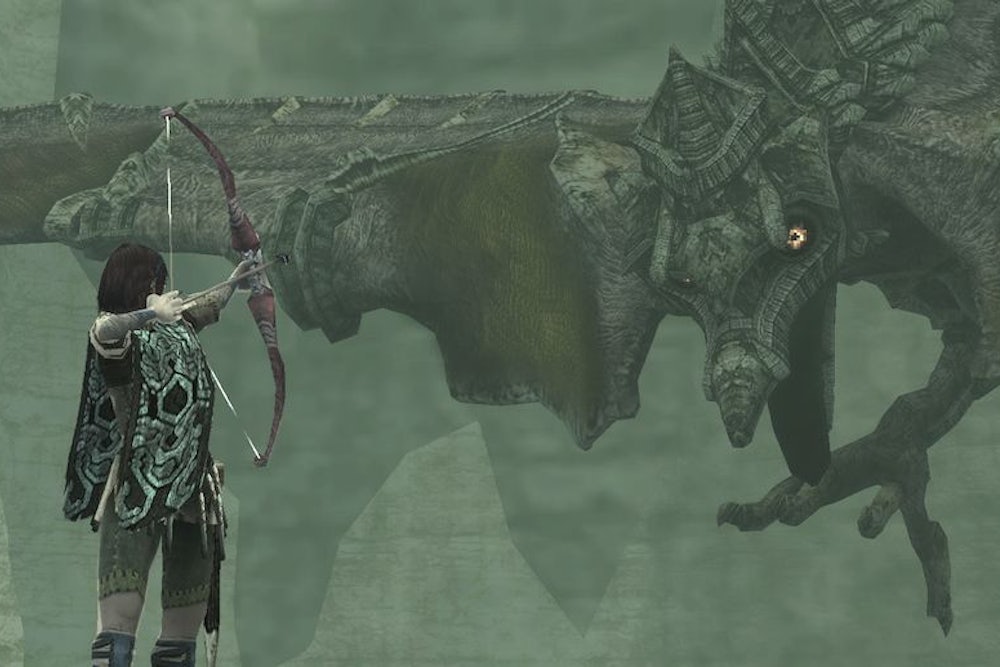

Console makers typically time the release of their latest machine with a number of anticipated games, a way of drumming up attention and convincing gamers to spend hundreds of dollars upgrading to a slightly improved version of the machine they already own. But The Last Guardian is not your common blockbuster: It is the sequel to 2005's Shadow of the Colossus, a radically minimalist game—created by the celebrated Japanese designer Fumito Ueda and published by Sony itself—that featured long stretches of meditation and had much more in common with Ingmar Bergman than it did with Grand Theft Auto. Like its predecessor, The Last Guardian is expected to be a visually arresting, spiritually stirring exercise in dreamlike play. Also like its predecessor, which easily made it onto Sony's list of its all-time greatest hits, Guardian is slated to bring the gaming company a much-needed windfall.

That a game focusing on the relationship between an unarmed boy and a giant baby Gryphon, and dedicated to exploring ideas and emotions rather than actions, could rise to such prominence is a testament to how comfortable video games have grown with experimentation. Increasingly, game designers are taking risks exploring the limitations of their craft—and increasingly, they are being rewarded for their daring.

Among the more lavishly rewarded is Limbo. Released in 2010 on the Xbox Live Arcade download service, it is the sort of nightmare that German Expressionism so expertly produced, a black-and-white set piece with stark lighting and strange shapes that make every moment creepy and foreboding. The game focuses on an unnamed young boy's effort to find his lost sister in a vast and punishing forest—located, the game informs us, on the "edge of hell"—and, to the extent that it matters, the gameplay revolves around solving puzzles. The real pleasure, however, comes from being forced to contemplate death, never too subtly: Make the wrong move, and your scrappy protagonist meets a gruesome end. A slew of peculiar gory dismemberments later, the game comes to a maddeningly open end, making its deliberately disorienting plot even harder to fathom. It's as demanding and moody a work of fiction as anything cinema has produced in a long while, but its box-office intake was more Cineplex than art house: The year it was released, the game was the highest grossing title on Xbox Live, earning its small studio, Playdead, $7.5 million and 527,000 registered players. The following year, with the game introduced on additional platforms such as Apple's App Store, the number of Limbo players crossed the one million mark, making its developers enough money to enable them to buy back their company from their corporate investors.

But while Limbo and The Last Guardian innovate in ways that Hollywood might find familiar—bending the form rather than breaking it—other titles go much further. When you start playing the desktop game Activate the Three Artefacts and Then Leave, for example, all you see is a black dot on a white screen. Move closer, and the dot is revealed to be a complex geometrical structure, an Escherian maze that soon proves impossible to master. Frustrated, you start noticing that the maze emits a high-pitch note, and that the note's frequency changes with each movement you make. To find the objects hidden in the maze, and to find your way out, all you have to do is listen very closely and, literally, play it by ear.

Because video games offer a predominantly interactive experience, and because interactivity is such a porous concept—it can require an intense, frequent button-pressing or just the occasional click, and it appeals to all senses together but also to each discretely—the opportunities for experimentation are vast. Munawar Bijani, for example, realized this fundamental truth about games as a child: He was born blind, but discovered he could beat his friends in fighting games just by following audible clues. Last year, he released his own game, Three-D Velocity, which features a blank screen yet recreates all the kinetic mayhem of classic action games like Street Fighter—but using only sound.

And yet, technological capacity alone does not explain the current wave of experimental games. Other art forms have similarly benefited from cheaper content development tools and more accessible distribution platforms, yet few filmmakers and photographers have embraced these freedoms as giddily as game designers have. The reason is cultural: The hacker ethos reigns among gamers and designers alike, which pressures the industry to innovate—and to do so cheaply and quickly. Nearly every month, gaming hackathons, sometimes sanctioned or sponsored by large gaming studios, are held in cities around the world, encouraging budding and established designers alike to conceive of, program, and publish a game in just 24 or 48 hours. These competitions spawn games that are more abstract ideas than refined entertainment products: Bathos, for example, one of the more talked-about indie games of the last few years, was created by a single person, Johan Peitz, over the course of one weekend, as part of a large gaming competition called Ludum Dare. It features a single screen, and only one challenge: Find a way to escape a locked cell. It is not so much a puzzle as an existential riddle, forcing gamers to consider the limits of their interactions with the machine in front of them, as well as the nature of language, the quality of thought, and other heady stuff. (If that last sentence was vague, it's because anything more concrete would spoil the fun: The limits of knowledge and the mechanics of uncertainty are what Bathos is all about.)

Sony, then, could go on all it wants about its achievements in electrical engineering, but for me, and for many other fans, the company's true feat is its investment in experimental games like The Last Guardian. The same goes for the video game industry at large: It's young enough, technologically savvy enough, and sufficiently blessed with consumers who reward any attempt at design innovation. It is this spirit of relentless innovation, unparalleled in the culture industries, that has propelled video games to such great heights—not new consoles that look a whole lot like the old ones.