We all crowded against the right-side windows as our tour bus crept up on the Amish. There were three of them—brothers by the color and cut of their hair—and they sat in descending order on the driving bench of a horse-drawn cart. As they rolled on, some rusty contraption plucked cornstalks out of the ground and fanned them on the cart’s bed.

“Do not take pictures, y’all!” begged our driver and guide, Gail. “They’re huge on the Second Commandment, which means no graven images, no pictures. Please. Every time. No pictures.” We were a baker’s dozen, a couple families and some seniors, and we’d only just begun this three-hour, handicapped-accessible tour of Amish farmsteads.

“These boys don’t need a license to drive that baby,” Gail informed us in his southerly lisp. “Y’all know the buggies, but here’s one for you: Eight percent of the Old Order Amish here are millionaires.” He explained that, nowadays, most supplement farm income by selling furniture and handicrafts to tourists. Some even operate small-scale workshops that fill orders for retailers like K-Mart. They keep overhead low and won’t expand past what’s prudent. “And more people come to see them now than go out to Ellis Island. Ten million a year. Who’d’ve thought?” Gail checked us in the rearview. “The Amish, rivaling the Statue of Liberty.”

We pulled neck-and-neck with the cart. Some sound buzzed around the horses’ two-beat trot. The middle brother stood with the reins.

I myself found them stirring. Strapping, blue-eyed brothers, harvesting corn in 2012! No incessant Instagramming, no real-time Twitter updates: Jacob’s got the reins, FML.

A dozen camera phones captured the boys with fake mandibular clicks and Gail sighed, “Goddamnit.” As my window came level with them, and I framed a picture, I realized that the sound underneath the clopping was Kris Kross’s “Jump” issuing from a hidden stereo.

I stared at the oldest, inches away. A little flare of mischief danced in his tourist-jaded eyes. Then he faked a lunge, to see if I’d balk, and I did. He laughed as he passed from my window to the one behind.

I’d come back to Lancaster County, in the southeast of Pennsylvania, because years ago, when I was driving home from a work trip, I took a detour through Amish country and happened upon something that I’ve thought a lot about since.

That day, I stopped at a one-room schoolhouse. It was barely visible from the macadam lane, brick and vinyl-sided behind a woodworking shop and a house selling brown eggs. I would’ve never found it had I not typed “New Hope School” into my GPS.

Simple wood fences ran along the lot’s perimeter and kept me far from the Amish kids enjoying recess. Some preteens huddled around back. Others hung linens on a line to dry. A chain of downy-headed toddlers pedaled Big Wheels across a field where, in 2006, a milk truck driver walked into the old schoolhouse, barricaded the door, and shot five Amish girls to death.

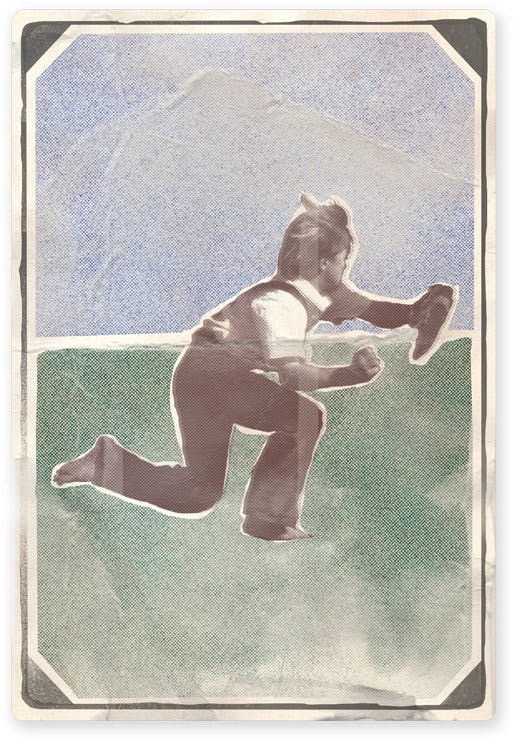

A hard breeze combed through the surrounding cornfields, a shush I spun around to appreciate. Then I noticed the backstop. Not just saw it, but realized that all the other Amish schoolhouses I’d driven by—they didn’t have hoops or goals or uprights in their playfields—they had backstops and baseball diamonds. One boy ran barefoot across the grass and positioned his shoes as bases. Then several more joined him, and they side-armed a ball around the horn with terrible mechanics but unflinching competence. A lefty took up a bat, and I took a few steps back, understanding now that the fence I stood behind doubled as the right-field wall.

He was a new teen whose taut physique had him looking like a system of ropes and pulleys. He stroked a ball over my head, laces hissing. When I sneaked back a few minutes later, he was fielding impassively, scooping and throwing with kinesthetic tics I remember having once, when I was little and in love with the game, before coaches smoothed all that out. They made him seem more authentic, more faithful to the form, like warps and bubbles in handblown glass.

The Amish play baseball! I thought. Of course they do.

What’s become of baseball? We don’t seem to want to play it or even watch it anymore. Participation in Little League has been dropping steadily for the past two decades. The nationwide player pool for slow-pitch softball has shrunk by a third since 2000, mostly in the 25-to-34-year-old age bracket, the biggest decline of any team sport other than wrestling. Meanwhile, this past year, as “Sunday Night Football” repeated as our number-one-rated primetime program, fewer people watched “Fox Saturday Baseball” than ever before. And the World Series—a quarter century ago, more than half of our nation’s televisions were locked into the deciding game of the 1986 Fall Classic. In 2012, barely 12 percent tuned in.

It feels like a fall from grace. I used to play in leagues year-round and watch the parade of home-run highlights on “Baseball Tonight” after prayers but before bed. Afternoons, I’d shag flies in a drainage ditch with my dad, because nothing back then made me feel as good as that immaculate moment when the ball went from white reticule hovering on blue sky—pock—to unseen kernel seeding a glove.

The game is so freaking boring, though! Am I not right? Tune in to the first half of a doubleheader held in Colorado on a Tuesday, and you will start to taste your own mouth, displeasedly. One of Colorado’s guys takes 30 seconds to throw a single pitch.

What baseball is is anachronistic. This is what’s most celebrated about it, the single narrative sweep of a game that’s changed little if at all over the course of seven generations—how me and a farmer sent forward in time from 1860 could sit down and enjoy nine innings with few or no expository leanings-over necessary.

But this is also what makes baseball so oppressive, so dense with history and numbers and precepts. If you want to get into it, you have to be OK with yoking yourself to the game’s considerable weight. It’s like an inheritance, a gift old people want you to accept, maintain, and someday pass on. Which, really, is the last thing any one of us wants when he’s young.

Before heading back to Lancaster, I looked up Amish baseball online and got a lot of apocrypha. There were never-updated Web pages listing Amish teams as the 18-and-under Ohio state champions, as the winners of a Texas “world” softball tournament. Depending on your blogger, they belted dingers and rounded the bases full-bore, in silence, without moving their arms; or else, they were dirty as all hell, flapping elbows on the base paths, coming in spikes-high on slides, their dogged consciences not extending to sport.

I did find one trustworthy story reporting that, in the late ’40s and early ’50s, Amish ballplayers in Lancaster were recruited onto semipro teams. They played under assumed names so no neighbors would spot them in newspaper box scores. One of the last of them, a late pitcher whose deception was never found out, had a nephew living in the area, a prominent business owner.

“LANK-uster County,” Jim Smucker corrected me when we shook hands in the gift shop of his Bird-in-Hand Family Restaurant & Smorgasbord. Smucker has long acted as a sort of docent to Lancaster’s tourists, holding weekly Q&As for the guests of his restaurant and his inn next door. His parents were apostate Amish, and he was raised a practicing Mennonite, which makes him like a Reformed Jew compared with the Amish ultraorthodoxy. Most of his friends and neighbors and employees, though, are Old Order.

He sat us in one of the roped-off wings of his recently expanded restaurant, laying his cell phone on the tabletop, where it would chitter between us throughout our conversation. “Amish contractors built the original,” Smucker said and gestured to the huge, rectangular, irregularly windowed place. “And they’ve built each addition.”

Smucker then launched into a brief history of the Amish, explaining that what began three centuries ago as a handful of families escaping persecution in Europe by sailing for the nascent Pennsylvania colony is today 273,700 adults and children spread across 30 states and the Canadian province of Ontario. (Though two-thirds of them have remained in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana.)

Amish belief then as now is completely grounded in the New Testament, which they hold to be the sole and final authority on all things. From it, they take their impetus to remain separate (“and be not conformed to this world”—Romans 12:2), as well as their orders to renounce violence in all spheres of human life, to refuse to swear oaths, and to obey literally the teachings of Jesus Christ. Still, they shun their undisciplined and wayward, to make it a little easier to keep the community of faith intact.

And the Amish are a true community, in every sense of the word. They believe that what we call “individualism” is actually pride, or, more bluntly, selfishness, which opposes God’s will, which should be yielded to with a dedicated heart. This communal spirit is regulated by an unwritten code of conduct, the Ordnung, which prescribes clothing and grooming and language, and prohibits things like divorce, military service, owning or operating automobiles, taking electricity from public power lines, and installing wall-to-wall carpet.

Basically, the Amish way of living argues implicitly that tradition is sacred, that preservation is as important or perhaps more important than progress, that obeying and yielding are virtuous, that the personal reality might not be the supreme. And in this way, above all else, they take the integrity of individual choice really, really seriously.

Or, as Smucker summed it up: “The Amish are very intentional. Whereas we just take on everything we’re offered without even thinking about it.”

They’re Anabaptists, which means they don’t baptize babies but only those who can understand and accept responsibility for what they’re getting themselves into. They don’t cotton to the evangelicals and the born-agains. Declaring one’s self “saved” is presumptuous, prideful; the Amish simply live faithful lives and hope for salvation.

And, contrary to popular belief, they’re not luddites. They’ll use technology so long as it isn’t “worldly,” doesn’t connect to the outside, or pull one’s mind away from the task at hand. Solid-state gas engines are OK, as are battery-operated calculators. If a machine can be retrofitted to run off oil or hydraulics, it’s allowed. Appliances may run off battery power. Cars may be ridden in if driven by an Englisher. (Anyone who isn’t Amish is “English,” because they don’t speak Pennsylvania Dutch.) Rollerblades are fine, and wood scooters, but not bicycles, because they, like cars, take you too far too fast too easily. Newspapers, trampolines, and gas grills: all kosher. Central heating systems are not.

Therein lies the problem they have with a lot of modernity: it’s fragmentary. And insidious. You allow central heat, and next thing you know, everyone in the family could then leave the fireside after dinner to go off to their own warm rooms. This is why the Amish live apart from us. So that they might remain whole.

Smucker himself has lived in Lancaster his whole life, save four years at college. When he came back, he played ball against the Amish in local park leagues and at the field he built into his brother’s corn.

“Are they good defensively?” I wanted to know. “It seems like they’d be good defensively.”

“MMMmmm . . .” he said, pushing all of his mouth to one side of his face. “It can be sandlot stuff. Cow-handed batting stances, Bob Tolan swings. Just terrible mechanics. But they’re so good despite that.”

Baseball, he went on, was forbidden by church elders around 1995. Baptized men had been wearing uniforms, and traveling to play league matches, and neglecting their duties at home. So, now, the game is strictly for the unbaptized. What I saw in the schoolyard was the noncompetitive stuff all kids play until the eighth grade, when their formal education ends. (“Knowledge puffeth up”—1 Corinthians). The only ones who can ball for real are the boys who have entered Rumspringa, the few free years of “running around” in the secular world that the Amish allow their youth (and about which we make feature-length documentaries and National Geographic Channel reality shows).

Rumspringa—ostensibly a time for finding a mate—is a kind of inoculation. A manageable dosage of culture is introduced to unbaptized Amish, the hope being that this exposure will keep them from succumbing to the whole pathology later on. From their sixteenth birthday ’til their mid-twenties, they sample what they’ve been missing—cars, hip-hop, food courts, double plays. Then they make the biggest decision of their lives: get baptized and get married, or forsake their world for ours.

“The unbaptized, if they play competitively in uniforms, that means they’re from a faster, more liberal district,” Smucker told me. “But you can still tell they’re Amish by how they carry themselves.”

“What should I scout for?” I asked.

“You’ll just know. But it’s getting less and less apparent. How are you gonna keep ’em down on the farm after they’ve got the MLB app on their iPhone?”

“The ballplayers are losing their religion,” I said, pleased with the joke.

Not quite, he replied, suggesting that I look up Amish retention rates at the Mennonite Information Center a few miles around the way. About 85 percent of today’s Amish choose the church, I’d learn—far more than when there were semipro ballplayers about; as many, in fact, as at any point in their history.

Officially, the Amish spurn private telephones, but an Anabaptist academic I contacted snuck me a number. He told me I’d need to first leave a voice mail—the Amish have voice mail on their communal outdoor telephones, and they check it once a day—and then I’d get a call back.

And so, at the close of regular business hours one Friday, an Amish butcher rang my cell from the phone he hides in his basement. “All Amish kids are baseball fans,” he confessed. “My sons follow the Phillies very much. Avidly.”

He parleyed in bottlenecked English, this brogue through which do became dew and ill squeezed into eel. “They watch ‘Sports Center’ on their cell phones. What can I say? They’re in Rumspringa. I did the same. Or similar.”

He used to love baseball, he said, used to play all the time before it was banned. “It’s fine for kids to play. But as Paul says, ‘When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.’ ”

I said I had it on good authority that the Amish play ball in uniform or in civvies all over Lancaster. He claimed not to know. I badgered. I had to see them in their element, I told him.

After some time, he exhaled and said, “Alright. Now. You don’t know who told you. And please don’t use my name. We’re not allowed to have our names printed. And you have to be careful, now. The Amish don’t want no reporters.” Then he asked if I had GPS and gave me coordinates.

I waited two full days at these coordinates. Empty clasps clanged against a flagpole. I had no idea a cow’s moo sounded so frustrated. To do something, anything, I started and stopped e-reading Ball Four and The Natural and Roger Angell’s baseball compendiums. I flipped between Bull Durham and Moneyball and Field of Dreams on my tablet in the shade. Nothing.

Some weeks later, after a couple more trips spent staking out diamonds around Lancaster, I settled on one behind a century-old general store. It had a hitching post, sheds for dugouts, and a two- story chain link fence about 300 feet from home. I installed myself on a bench beyond the fence in left field. I waited. At some point, I fell asleep.

When I heard a thud and opened my eyes, I saw a small boy riding by atop a miniature buggy pulled by a Shetland pony. I figured I was dreaming. Then came another thud, closer, and I turned my head in time to dodge a yellow softball one-hopping directly at my face.

Ballplayers, at last. Ten of them. They wore athletic shorts and cleats, but I knew they were Amish because they chattered misaligned English in elfin accents.

“Attaway Amo!” shouted the guy nearest to me in left. “That’s how you Tootsie Roll!”

This was practice. They were a competitive slow-pitch team. I tossed the softball back over the fence. The fielder said, “Sorry, sir.”

They were from liberal families. They had filled the parking lot with $40,000 trucks and big white Escalades bought with the money they earned working trades or construction right after middle school. (Should these boys decide to join the church, their vehicles will wind up in fields full of near-new cars with FOR SALE signs in their windshields.)

The kid at bat launched one on a directly proportional incline. It cleared the fence and burst the treetop above me, the ball then falling into my hands ahead of a clump of flittering leaves. I asked if I could shag with them. They waved me over and I ran to get my glove from the trunk of my rental car.

I would prefer to keep with genre standards and describe these boys as a dugout’s worth of motley loners, but I can’t. They were as chippily uniform as a litter of golden retriever puppies: long limbs, tanned bodies, unstylish haircuts. The sons of farmers and craftsmen. They used Pennsylvania Dutch for jokes they didn’t want me to hear; for everything else, musty English learned in school.

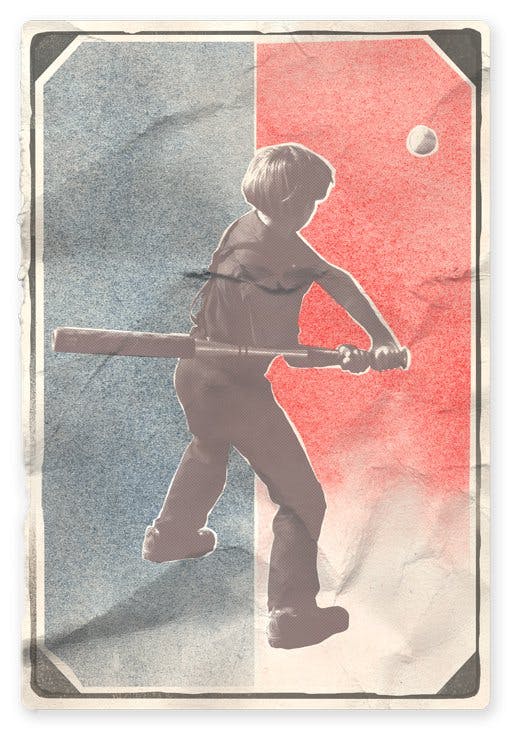

They were 18, 19, but clearly had never been coached. Some stood in the batter’s box with their feet touching. One lefty pinced his right knee and elbow together crabwise before swinging. Another held the bat above his head as if preparing to beat a snake to death. Categorically, they creamed the ball.

In the field, their each throw sizzled. They jumped into the path of hit balls as though playing through a memory. They dropped to one knee, two knees, laid out horizontally—whatever it took to block grounders. A freak hop bloodied the shortstop’s nose, and the cheer from right field was, “Ya, looks like ya need another Red BOOL, Morty!” Everybody laughed but me; Morty’s smile was wishboned by blood. “Ya, buy it with your credit card, credit card!” went the pitcher.

I’ve played enough to feel OK saying: Never before had I seen a team of young men be so good without also being repulsively cocksure. These guys had a prelapsarian sweetness about them, this straight joy that I last knew as an adolescent dicking around with my friends Friday afternoons on a pebbly field behind a RadioShack.

I was never great or even very good. I couldn’t hit a bear in the ass with a banjo. My game was defense. I could play most anywhere, but I begged off from center field and second base. Center because of the spotlighted solitude of in-game fly balls. Second because the throw to first was so short. Both because there was so much time to think.

There exists home video of what ended up being my last Colt League game. In it, I expertly snare a two-hopper several steps to my backhand side, only then to just stare at the first baseman with the smiley grimace of a guy waiting to get punched in the face. When I finally force the throw from second, it scatters the upper bleachers. This was the first of four such throws. That was it for me.

Lots of people walk away from a beloved sport once they come of age. They tire of the game, develop new interests. That’s not why I dropped baseball. Baseball, I think, is different.

What makes it such a great children’s pastime is also what makes it so goddamned difficult for even proto-adults to play well. As major-league pitcher Ron Darling famously said: “Most people have the physical ability to play this game. To excel in it, I think it’s in your head.” What he means is: If you are conscious of yourself—like, at all—baseball will eat you alive. It measures you against an absolute standard—1.000 batting average, 1.000 fielding average, 0.00 earned-run average—and it reminds you every step of the way that you are falling short. If you can’t handle that, if you get interrupted by the infinite regression of anxiety and doubt (. . . I made that throw, which excuses me for striking out last inning, but I’m still 0-for-11 lately, and I double-clutched on that fielder’s choice, which Ross’ll remember but not mention because he stockpiles my errors like they’re his own critical deterrents, and SON OF A BITCH, back up the bag, Ross is looking . . .), you are fucked.

To be good, you either have to be so self-assured as to be nigh catatonic, or you have to choose to pay attention in the most literal way. That is, you have to realize that your attention is a valuable, finite resource, and how you choose to spend it the one skill—not speed, not power—that separates the wheat from the chaff.

“Control your thoughts before they control you,” read the pubescent marginalia in my dog-eared copy of The Mental Game of Baseball, the big-leaguer’s Bible. Dear to me was its koan, “If there’s no future, there’s no distraction.”

According to the book, the easiest way to achieve this stillness was to vacate yourself and enter the mind of the pitcher or the batter. To be forever considering: What’s the pitcher’s best stuff, and what’s his best today? What sequence of pitches has he gotten this guy out with in the past? What’s the situation in the game, and what does the hitter want to accomplish? Is there something about this ballpark and this day—short porch in left, wind blowing out, his last embarrassing at bat—that could affect that desire? Which base would I cover or throw to if he got his way? Or if he didn’t? What would be the permutation of all our failed intentions?

If not this empathy, then the book said your only other choice was to keep a lid on your brain. Force your conscious world to fit inside every next pitch. Abridge yourself. Play in a gnomic present. And labor to maintain this link to your surroundings, always, if you’re to have a snowball’s chance.

I couldn’t manage either. And the more I matured, the more self-consciousness snuck into the cracks of my play and pulled me apart like weeds taking ruins back to nature. I couldn’t help it. I was a head case.

The Amish, though, they didn’t seem to care who was watching. One after another, they stropped pitches over the fence. “Hyume run!” they said. “Holy smokes!”

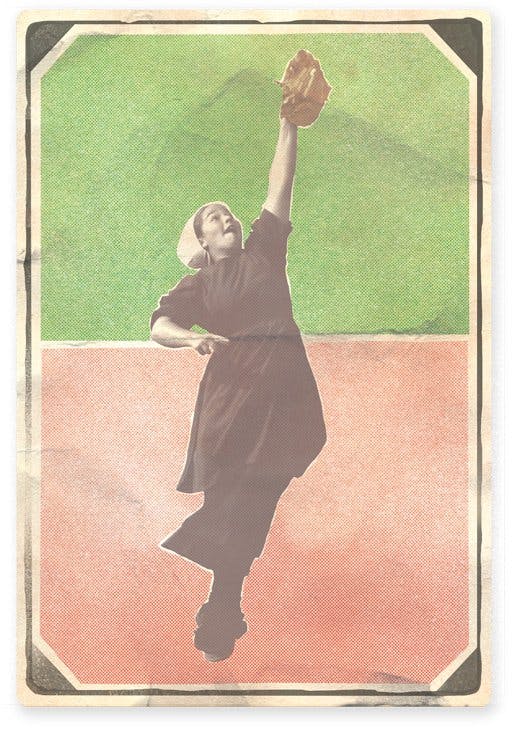

Four Amish girls in heart-shaped bonnets stopped walking dogs to curl their fingers around the chain links. They had light eyes and sheer cheeks. “You girls runnin’ around, are ya now?” asked Aaron, the left-fielder. He nodded to the boy at the plate who then knocked one deep into the gap. I took a few perfunctory strides. Aaron ran hard enough to lose his hat. Then he dove, snagged the liner backhanded, and rolled into a somersault before springing to his feet. The ball was sticking half out of the top of his glove—a snow cone, you call it—and he feigned a lick. The girls tittered.

As Aaron and I trotted in from the outfield, I asked how his Rumspringa’s been.

“Na, ya know. Other than ball, running around makes me feel restless.”

He told me they had a play-off game that evening at a different park. I made him type the address directly into my phone.

Along the old Philadelphia Pike, between Lancaster City and Intercourse, traffic coagulated. Tourist vehicles braked to take in each buggy that jangled down the extra-wide shoulders. So many signs were crowded at the road’s edge—signs for clocks, jams, buggy rides, pretzels, Old Amish apples, Old Amish peaches, Old Amish furniture, country knives, a stay at the Old Amish motel, the Amish Experience—and they all were angled and a little desperate, like raised hands eager to answer a question. This was something I’d read about, how acres of farmland were going for $17,500-per at auction, so only half of the Amish in Lancaster could still afford to farm. The rest were moving to other states or adjusting to nine-to-five workdays punctuated with leisure time. At a red light, I watched a family of six hit the Susquehanna Bank branch, barefoot.

Stopping and going, I snapped photos of sprawling Amish estates, their roofs flannelled with solar cells. When I looked through the shots on the digital viewfinder, I noticed that surrounding the farms were English homes on artificial rises. They were stone houses of an imagined rusticity, built by well-off retirees who had push-pinned American flags on sticks all over the property. These managed to seem both really invasive and really conscious of not seeming invasive, looky-loos with hands folded behind their backs.

This is the attraction, this idea of the Amish. That we might come to Lancaster and encounter what appears to be our past, the simple, rich, idyllic existence back when our freedom from had yet to develop into our freedom to. Here’s what we could have been had we stayed the inevitable.

It’s both condescending and a self- deception, of course, this idea. But in my car, I had to admit: It’s hard to lay off of. When I saw Amish in buggies waving across two lanes of traffic, it cheered me up. Their homogeneous presence was a merry sight, like nuns in habits at the airport. It’s a relief to know that people still live this way, because as these sorts of Jeffersonian fundamentals shrink further from our world, I find it more necessary than ever that someone harvest summer corn, cultivate virtue, play baseball. Abandoning that would mean something about us was dead, or at the very least outgrown, irretrievable.

I took a spot on the bleachers next to a stout Amish man with a salt-and-pepper beard. He’d taken off his clodhoppers so he could fan his toes on the row in front. Our view past the outfield fence was a darkening one of barns riding the corduroy swells of corn like arks. The floodlights switched on.

“Looks like rain,” said the man next to me, whom let’s call “Dan” because, were his real name to appear in print, he’d be censured by the faithful. “What’s your phone say?”

This was the semifinal of a local league championship, the fifth game of a best-of-five series. The Amish boys had won the first two; the English men the last. About 80 or so Amish had come to watch. They outnumbered the English four to one.

Many were families, but most were young men from fast districts. They looked just like middle-American teens on television, all swooped bangs and skinny jeans tucked into fat-tongued sneakers. The few girls wore dresses and bonnets. The prettiest one sat in a truck that idled while “Call Me Maybe” spritzed through the cracked windows.

I told Dan that my weather app was saying all clear. In the dugout, the Amish boys brought it in and chanted, “One, two, three—KICK ASS!” before flowering their hands. I cringed and waited for the communal reprimand, but none came. A cloth-freckling rain began to fall.

The English team was sponsored by a construction company. They looked to be men of a mean utility, glyphed in sun-blanched tattoos. “I know it’s tough, but if he’s throwing that short shit,” their burly coach instructed them, “take all the pitches.”

The Amish boys conducted themselves through warm-up drills. They wore gray jerseys and white pants, some belted and some held up with suspenders. I asked Dan if he was cool with these kids wearing uniforms instead of their Ordnung-prescribed trousers. “For now,” he said. “When they’re married, their clothes will be their uniforms. In terms of God, I mean. When we’re walking, when we’re working—we’re always playing our position.”

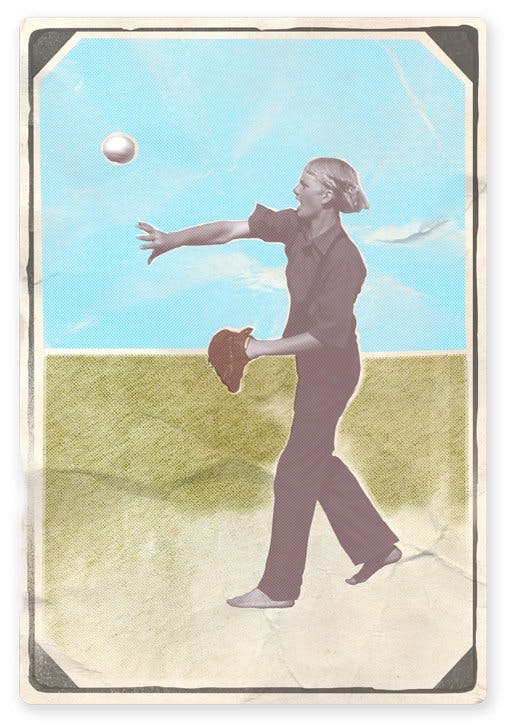

The first couple innings were tight. The Amish turned a smart 6-4-3 double play. The English retired them 1-2-3. They accepted umps’ close calls with nodded equanimity.

The rain picked up, sprouting umbrellas. In the field, the boys tensed and attended to the ball. The English cracked two home runs that left the park trailing tails of secondary sound. “Sit! Sit! Sit!” Dan called out to the Amish boy who’d just swung-and-missed so hard he spun off his feet. The boy then looped a double. “There you go, that’s what happens when you sit.”

Dan turned to me. “So, you’re a tourist?” The ease with which I lied and said I was visiting family startled me.

“Some think tourism is a new kind of persecution,” he said. “On account of we don’t want our souls marketed.” We commented on the irony of this, the disguise of plainness they adopted way back now making them glaringly obvious and strange.

“I don’t know,” Dan said. “We could never have stopped it. Now, we need it.”

The boys fell behind a few runs after succumbing to impulse in the field. They forced throws, overran balls, bypassed cutoff men. “Bah,” Dan went. “Playing young. In a hurry.”

I told Dan about this Rumspringa documentary I’d seen where all the kids went to these huge parties and had unprotected sex and did, like, meth and stuff and did that happen out here?

“We got problems just like anybody. Drugs, pregnancy. Some of that stuff’ll probably go on after this game is over. It’s being a child. But then that stops. Or it’s supposed to stop, if you make the right decision.

“You just feel silly after a while, running around. ‘Where am I going?’ Ya know? ”

Giving no notice, I touched his shirt. I rubbed it between my thumb and fore- finger, as though I was pantomiming the universal gesture for very costly.

He cocked his head and curled his lower lip under his upper. “You like it? My wife buys them in the store in town. She don’t wash by hand, just so you know. We’re not, what do you call—”

“Noble savages?” I offered.

“At the shop, I have a gmail. Washes ’em in the pneumatic washer, my wife.”

When Aaron the left-fielder walked to the plate with the score tied six all, the guys in the dugout hummed a ragged facsimile of “Here Comes the Bride.” The men in the bleachers stamped and hooted. One young lady in attendance put her face in her hands, wracked with either laughter or sobs. This, it turned out, was Aaron’s final at-bat before marriage, the last pitch he’d swing at.

I decided that I could not watch this. This was like sneaking into a bar mitzvah or trying to peek through the fogged window of a car parked on an escarpment. This was a turning point I should not be privy to.

On the unlit diamond to the east, four Amish boys in slacks and suspenders were playing pepper, a game where fielders crowd around a batter who slaps quick grounders into the array. I mumbled a hasty goodbye, fetched my glove, and joined them.

I gobbled up the first dozen balls hit my way. After each one bellied my pocket, I felt good, great, like I’d slotted a coin in a machine that let me play myself a little longer. I whipped the ball back to the batter, who chopped it at someone else.

Then that good feeling vanished. It always vanishes, because it’s always contingent upon the next ball.

The boy off my forehand side fielded by reaching down with his one hand while raising the other straight over his head. When the ball popped in his mitt, he slapped his hands together in front of his grinning face. He was gawkily storkish, and very consistent.

And I thought: This boy knows nothing of the yips. He will be forever in the world’s childhood. If only I could play as purely and single-mindedly as he does.

But doubt nagged: Does he really play unknowingly? And even if he does—did he really ever have a choice?

I could’ve asked. He was right there.

But what if an Amish boy also felt turned around, overwhelmed, scared, like he was trapped in a place many times too big for him, where his only recourse was to run from person to person and place to place to see if anything bore any relation to him, or if it might not help him get to where he thought he should be, wanting to cry but trying hard not to, wishing most of all he was in a warm, small, familiar place?

We played pepper in silence. On the other diamond, the roars of the Amish were less frequent but more intense, the sound of faith unstoppered. I tried hard not to fuck up. I thought of not throwing behind the batter, and then did, more times than I’d like. The other boys handled the field with an uneventfulness that resembled meditation.

Right down the street from the Amtrak station, in the husked industrial half of Lancaster City, was a minor-league baseball stadium with GAME DAY signs in the parking lot. I decided to catch a few innings while I waited for my train.

I got a seat behind home plate for twelve bucks. A team from Long Island was visiting the Lancaster Barnstormers, whose logo is a cock-topped weathervane. Around the stadium, there was all this stuff to do other than watch baseball—merry-go-round, inflatable slide, pit barbecue, dunk tank—and all these families doing it. Maybe people will always at least go to the games. They can be like a historical farm, a nice-day alternative to taking your family to the Air and Space Museum and not reading any of the placards.

Photo by Kurt Wilson

A small-bore sun setting in the west made the clouds glow along their margins. At the end of the first, I spotted three traditionally dressed Amish teens in my section and decamped for the seats behind them.

The boys were in Rumspringa. We talked about the schoolhouse shooting, how the Amish set up a charitable fund for the killer’s family, attended his funeral, and comforted his widow and parents, one man holding the killer’s sobbing father in his arms for an hour. The boys quieted down whenever the pitcher began to toe his rubber. The fielders held up as many fingers as outs, the repetition to make sure that the appropriate thought was firmly in mind at the appropriate moment. “His name was Charles Carl Roberts IV,” one of them said during a time-out.

The Barnstormers’ in-house M.C. trawled the rows around us for between-innings tricycle-race volunteers. The Amish kid sitting in the middle wanted to know if I’d been to college, and I said I had. He stared at the alluvial veins on the backs of his hands. I blurted out: “No, but you’re lucky, though. School ’til eighth grade, then labor?” I got a little agitated, actually. Restricted consciousness? Making a choice to be protected from the burden of choice? Did they not know how blessed they were?

The one on the left said, “You could join, y’know.”

I daydreamed on it for a whole inning: sweatily carpentering, whispering to horses, sniffing handfuls of crumbly manure late in the day—whatever one does on a farm. And never knowing what else I might have become. How does that sound? Choosing to live buffered by a freedom found not in options but the diminution of self? Having faith that peace of mind will become one day possible and then effortless after that? I lost track of balls and strikes. The clouds burned out on the last day of summer.

Then I asked, “Hey, you guys didn’t happen to be at this softball game the other night?” They nodded at one another. I told them I left a little early and wanted to know who came out on top.

“Oh,” said the middle Amish. “The English went on a tear. They mercy-ruled our boys in the seventh.”

Kent Russell is a writer living in New York.