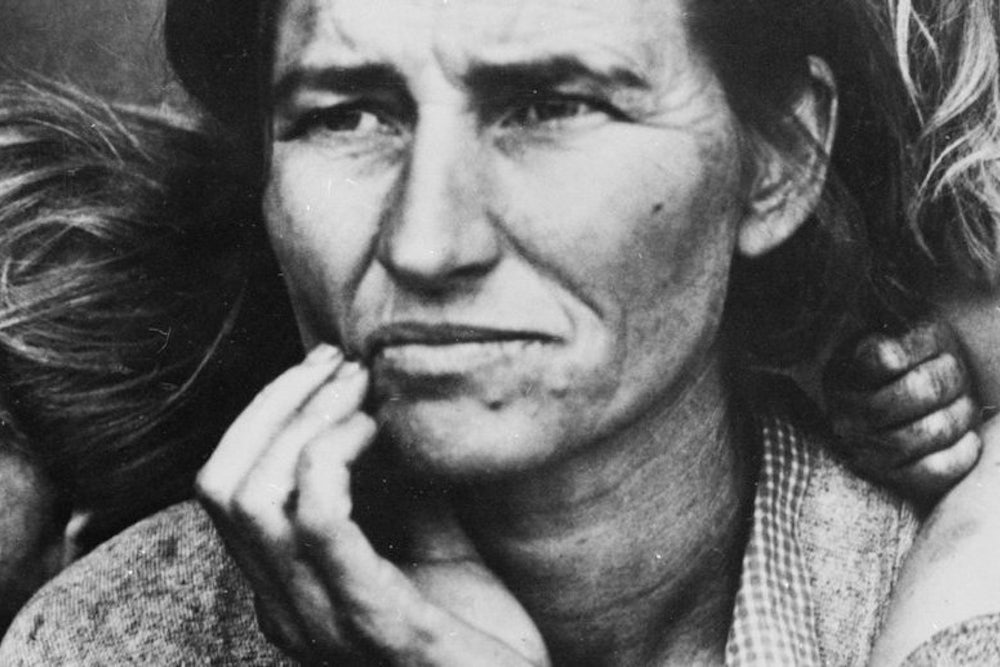

The title character in Marisa Silver’s new novel, Mary Coin, is based on the subject in Migrant Mother, Dorothea Lange’s famous photograph of Florence Owens. This is the image that came to stand for the Great Depression: a woman surrounded by her children, looking as though she has nowhere to turn and is carrying the weight of the world.

In writing about a figure we know almost entirely from an artistic rendering, Silver joins a crowded genre—Tracy Chevalier, for instance, rose to fame with her speculations as to what, exactly, Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring was thinking. (She’s gone on to write other speculative works about visual art; another of her books is about the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries.) Irving Stone’s The Agony and the Ecstasy purported itself a “biographical novel” about Michelangelo, bolstered by research but also subject to the novelist’s license. Recent novels about the lives of photographer Edward Muybridge and engraver William Hogarth seek to flesh out the biographical component. Some works seem to exist only as a sort of scandal sheet for those familiar with art history, a Louvre-based issue of Us Weekly: Artists and Models—they’re just like us!

What sets Mary Coin apart, however, is that Mary’s life pulses with real and relatable humanity before and after her moment as an artistic subject. This book starts with the image, but doesn’t stay within the facts of that image: This is not a novel about Lange, or Florence Owens Thompson, the actual subject of Lange’s lens. To start, Silver’s characters do not share the names of their inspirations. But more substantively, Mary Coin has a personal history that reads like one of Silver’s expertly drawn short stories, a series of disappointments and tragedies small and large rather than a dramatized biography. And Vera Dare (this novel’s Lange figure) shares Lange’s real-life disability (a pronounced limp) but has a brash, almost snobbish quality that uses little actual biographical detail from Lange’s life. In creating such characters, Silver seems to be refusing to make any presumptions about the motives of artist or subject, focusing instead on the marginalia—everything that came before and after the moment of creation. The reader's yearning for inside information on whatever might be the "real" tension in the artwork goes—in a manner that is frustrating before it is compelling—unfulfilled.

Mary is an insecure and impoverished young woman in Oklahoma when the novel begins; it follows her fall from lower-middle-class to true poverty, alternating with Vera’s rise to mild repute as a photographer. (A third plotline, about a contemporary professor of “Images,” fails to pay off until close to the novel’s end.) In Mary and Vera’s first meeting, the photographer emerges from a car in a chic hat and asks Mary, who is scavenging for dead birds, to grant a portrait in order “to show the government how things are.” Vera sees Mary schematically, not as a woman but as synecdoche of national problems and as a “type” of photographic subject to be checked off a list. Silver’s writing, in Vera and Mary’s glancing interaction (they meet only once, when she takes the picture) reads less as an indictment of Lange than as a sophisticated reading of her work, one with consequences extending into both fictional women’s futures.

Mary Coin falls short, however, when it attempts to diagnose explicitly the problems of reducing a whole life to a single image, a matter that the novel has been skirting all along. Vera feels guilty for having brought Mary fame without remuneration and for capturing her at her lowest moment. The guilt manifests in the form of an undergraduate who just discovered Susan Sontag’s On Photography: “The camera did that—it asserted your significance and robbed you of it at the same time. It looked at you and then turned away.” This is a disappointingly facile manner of representing thoughts that should, based on what we know of Vera, be complicated and upsetting. It’s what a roman à clef version of Lange would say, not what proud and supercilious Vera would.

Thankfully, such moments in the novel are uncommon, and Silver’s characters are, for the most part, convincingly complex. Vera is not simply an armchair philosopher theorizing about the pitfalls of photography—she is a woman whose simultaneous ambition and disability have made her unable to understand people like Mary, and to favor her own reading of events. Self-centered to the end, she sends Mary a letter thanking her for providing “a kind of … is it happiness?” Vera’s happiness comes from recognizing who she believed Mary to be, a recognition that, it seems clear, Vera has applied ex post facto in order to assuage some guilt. If there was an ecstatic instant for Vera, a moment at which artist and medium and subject all became one, I missed it; Silver stretches Vera’s coming to terms with her work over decades.

And Mary is not merely a righteous woman who feels she has been exploited—her inner life is not plotted against the contemporary novelist’s star chart of psychological malady and trauma. Raised to react against calamity after calamity, she grows into middle and old age uncertain as to what the photograph has meant to her. She reflects on Vera’s obituary: “There were unhappy things that you lived with so long that you missed them when they were gone.” The only confrontation that eventually takes place occurs when Mary makes a late-in-life visit to see her own image at a museum. “You can see it all in her face,” says a passerby.

In another novel, the moment would be maddening: It reads, here, as an ironic moral: Mary is soon to die and shall later be forgotten, but her decontextualized image will long survive her. But the reader, unlike the glib viewer passing by the image, knows precisely what has happened to Mary, and what the viewer cannot see. Silver has done what the most imaginative museumgoers do—refuse simply to accept the easiest explanation for what a photograph conveys. Silver’s contempt for the glib museumgoer, presuming much but wondering little, bleeds through in that “You can see it all,” and mixed feelings about Vera’s claim that there was recognition in her photograph: Silver refuses to accept that truism of writing about artists, that the art simultaneously explains all and must be explained further through exposition.

What Silver ultimately does in creating characters rather than extrapolating icons is in line with Auden’s poem “Musee des Beaux Arts,” in which he writes about what happens at the margins or beyond the frame of a Breughel painting. “[W]hen the aged are reverently, passionately waiting / For the miraculous birth, there always must be / Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating / On a pond at the edge of the wood.” Mary Coin is set, to its credit, on the edge of the wood.