In the aftermath of Amazon's purchase of the social book website Goodreads last week, the tech press went into a speculative tizzy: How much did the retail behemoth pay for the platform and its 16 million bookworms? The question isn’t motivated purely by envy. While acquisition prices tell us how rich a company’s founders have just become, they also signal what to expect from the new union and serve as benchmarks for future investments. That’s why backsolving Silicon Alley deals is one of the tech press’ favorite parlor games.

Businessweek pulled out its calculator, took a look at the going rate per Goodreads user, factored in likely revenue growth, and came up with a number: $1 billion. Eye-popping, sure, but all things are possible in the age of Instagram. Still, Business Insider took the conjecturer to task for his assumptions, and AllThingsD found actual sources saying the deal was worth more like $150 million. We still don't know for sure.

How could people have come up with such wildly divergent answers? A business is a business, after all, with certain assets and comparable market rates. You shouldn't be able to justify anything.

You basically can, though. And the reason why has to do with the way the tech landscape breaks down these days: A field of essentially five or six warring factions, which—depending on the particular fight at hand—includes Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft. They're all locked in a death struggle for access to content and the means of distribution. A smaller business isn't just worth the value of its talent, technology, and existing user base. It's also worth whatever it takes to keep it from falling into the hands of a competitor.

"In the world that we're in right now, where you have basically a group of monopolies trying to make themselves impregnable in a particular part of the content world, keeping a company away from your competitor is the biggest value of all," says Jonathan Aberman, managing director at the McLean, Va.-based Amplifier Ventures. "The intrinsic value of an asset if you're trying to build a monopoly is never going to be based on the true market value of an asset. It's going to be based on the negotiation between how badly do you want it and how much do the shareholders want to sell. Sometimes the result is a price that doesn't meet any objective standard of fair market value. But so what? This is not like buying and selling cars, where there are millions of cars."

Take the aforementioned Instagram, which Facebook bought last year for $1 billion in cash and stock. Until then, it was just a fun app that people used to broadcast artistically rendered snapshots. But photo sharing also happened to be a crucial front in the war for social eyeballs, and Instagram would've provided a huge boost to Google Plus, had the search giant thought to buy it first—an existential threat to Facebook's future growth. (And in the networked world, speed is essential: Google bought another photo-sharing app later, but hasn't come even close to Facebook's dominance in that category.)

"Facebook says 'Crap, If Google buys Instagram, they have a great photo sharing app, photo sharing is what a lot of people use Facebook for these days, all of a sudden Google Plus becomes relevant, and we can't let that happen,'" Aberman summarizes. "'So we've got to get in there and buy it, and we will pay a ridiculous number if we have to, because we're spending funny money anyway.'"

Viewed through this lens, a lot of other eye-popping price tags—like Yahoo!'s $30 million acquisition of a 17-year-old's news aggregation app—start to make more sense. Even if Yahoo! never fully monetizes the service, it's worth the cash to prevent someone else from doing so. In 2011, the latest year for which comprehensive figures are available, Google spent nearly $2 billion on acquisitions, Amazon spent $771 million, and Apple spent at least $776 million. Sometimes it's not even about the product so much as the people who invented it: Big web companies often buy whole companies just for their talent. Who knows what damage they could do if they went to a competitor?

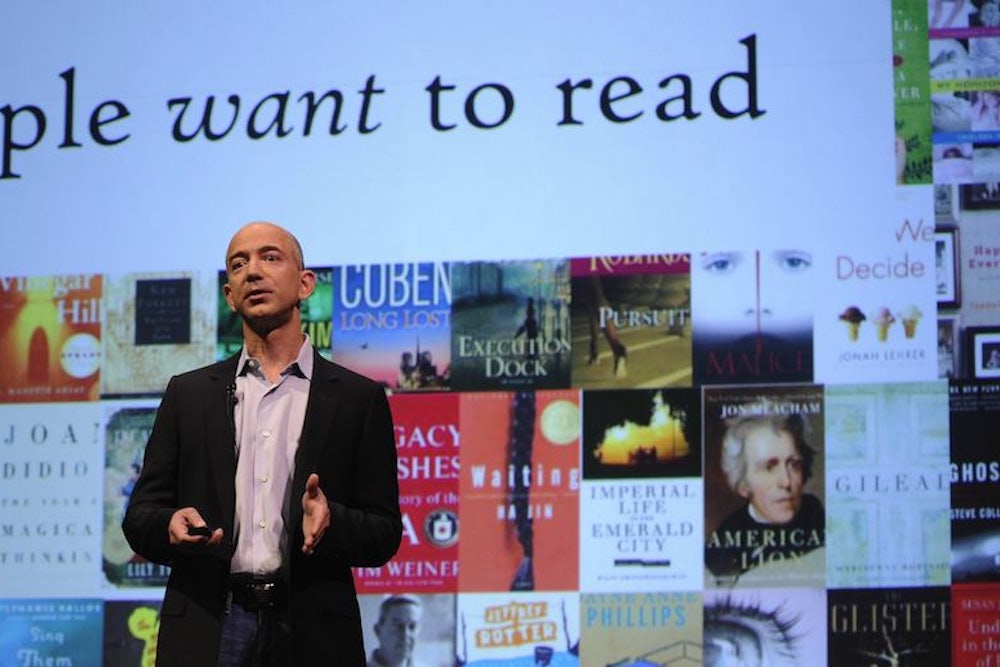

So, back to Goodreads. There were many compelling reasons for Amazon to buy a robust social network that provides crucial insight into how people decide what books they like. Apple, which hasn’t built any social capabilities for its massive content platform, might also have benefited from the purchase. In this case, though, the biggest danger wasn't another web titan, but Goodreads itself: Had the founders decided to channel the indie sensibilities of its user base into becoming a publisher and distributor, it could have posed a competitive threat to the province of the Amazonian empire that still deals with books. So Amazon had to make it worth their while not to make that choice.

Now, Goodreads may not have set out with the intention of ultimately cashing in. And plenty of independent platforms, like Netflix, Twitter, and Foursquare, are so far making a go of it on their own. But more and more, that's the typical strategy for web entrepreneurs and the investors who get them off the ground: Design a feature for a larger company that will be a useful weapon in the battles over content, advertising, or search. Play your cards right, and walk away rich.

Of course, the web giants' appetite isn't infinite.

"Here's the problem," Aberman explains. "There are so many people starting these little companies than there are likely buyers. That is creating an enormous bubble that is already starting to result in a lot of disappointment."