No one is more preoccupied these days with Hillary Clinton's 2016 plans than the Beltway political class—not even the former presidential candidate herself. To hear some tell it, her decision will be dispositive for all other Democrats thinking of entering the race. And pundits and reporters aren't the only ones positing the "The Hillary Factor": No less than the House Democratic whip, Steny Hoyer, told BuzzFeed, “I don't know that anybody would run against Hillary…. If she runs, she clears the field.”

It's an understandable conclusion, given Clinton's stature in the Democratic Party and her 70 percent national job approval rating when she left office as secretary of state. An indication of how much less polarizing and how much more iconic a political figure she has become: 41 percent of Republicans expressed their approval. When Colin Powell stepped down as secretary of state, he had a 77 percent job approval rating. But by 2005, Powell was yesterday’s man, content to amble downhill from the peak of his career. Clinton isn’t at all about nostalgia and gratitude; her best years may lie ahead of her.

Recent press reports that big-dollar Democratic donors are hanging back, waiting for the answer to will-she-or-won’t-she, make perfect sense in light of her currently prohibitive front-runner status. But Hoyer needs to get out more. It really makes no sense that all Democrats need is to see a puff of white smoke coming from the chimney at 3067 Whitehaven and the 2016 nominating process is over.

Many Democrats would no doubt dearly love an uncontested primary amounting to the stately coronation of Clinton. It would spare them a spectacle akin to, say, the 2012 GOP primaries, in which another prohibitive front-runner came out on top, but only after a grueling process of fending off a seemingly endless procession of challengers. It may never get that bad for Clinton, but a tough fight for the nomination is far more likely than a contest in which no other contender shows up, and that’s true even if Democrats are practically unanimous that she will be the eventual winner.

People throw themselves into presidential primaries for all sorts of reasons, only one of which is the hope and expectation that they will be on the ballot in the November quadrennial. In 1991, the Democratic Party was having an equivalent will-he-or-won’t-he over the intentions of New York Governor Mario Cuomo, whom polls indicated would enter the race as odds-on favorite for the nomination. The possibility that Cuomo would run didn’t stop an ambitious young governor from Arkansas from entering the contest. I’m pretty sure Bill Clinton was confident that he could be elected president one day. But I’m not sure he was confident that it would be in November 1992. His campaign in its early months had some of the aroma of a practice run. And a practice run can be a very valuable experience; Ronald Reagan in 1976 is an obvious example.

Is there no youngish Democratic pol out there thinking eight or 12 years down the road? None of the following—Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, California Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom, representatives Chris Van Hollen and Patrick Murphy—would consider running a hopeless race just to generate national exposure and campaign experience, and to begin building a database to match their long-term aspirations?

Politicians have also been known to run for president as a way of becoming vice president. John Edwards was elected to the Senate from North Carolina in 1998, his first bid for public office, and would have had serious trouble holding the seat in 2004 if he chose to run for reelection. Either way, a dead end for his political career. So almost immediately, the new senator started giving speeches in Iowa. His relative inexperience made him an implausible presidential nominee, but a perfectly plausible vice presidential nominee. Win or lose in the general, the vice presidential nomination can be a way-station to an eventual presidential nomination.

Then there are the presidential candidates running their mouths, if I may offer homage to Marion Barry, the inimitable former mayor of Washington, D.C. Asked in 1990 about the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s reported ambition to seek public office, Barry famously replied, “Jesse don’t wanna run nothing but his mouth.” Although Barry was dismissing the possibility that Jackson would challenge him for mayor, the same comment might be germane to Jackson’s entry into the Democratic presidential primaries in 1984 and 1988. Jackson was running to advance a cause, not because he thought he could win. It’s probably fair to say that Republicans nowadays are more prone to this kind of behavior, but Clinton could also easily draw an opponent who runs to her left, mainly to make a statement.

Moreover, if Hillary Clinton does run in 2016, it won’t be the first time she has entered the presidential race as the overwhelming favorite for the nomination. Had Obama lost to her, he likely would have wound up with the vice presidency and very bright prospects for the nomination in 2016—all in all, not a bad outcome for someone with no more experience on the national scene than Edwards. But he didn’t lose to Hillary. And although there's no Democratic figure with political promise comparable to 2008's Obama, it hardly follows that no one would even bother to try to derail Hillary for a second time.

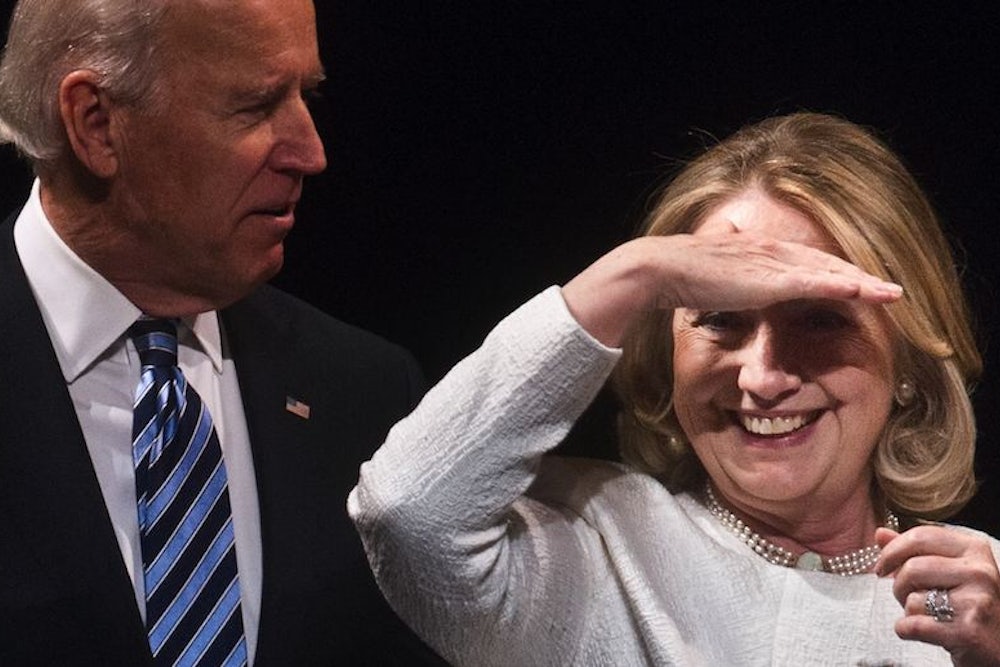

An early Clinton decision would bring swift clarity to the 2016 contest, and a late one would cause considerable Democratic anxiety. But it’s not within a front-runner’s power to claim the nomination by mere declaration—not when so many others have such tempting reasons to run, too. What, after all, might Vice President Joe Biden have to say about Hillary’s purported ability to clear the field? Come to think of it, a reporter will probably ask him any day now.

Tod Lindberg (@todlindberg) is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford.