The most important piece of journalism so far in 2013 was commissioned by The New Republic. Unfortunately, due to a dispute, it appeared in Time, an obscure publication where no one will read it. It is so good, though, at clarifying our health care problem that it is worth digging up, even though it is two months old, and despite a few conceptual errors and confusions, undoubtedly inserted by the editors at Time. Any health care executive who hasn’t read Brill by now (OK, or at least skimmed it—it is very long) ought to be fired.

Didn’t we just take care of all that with Obamacare? ‘Fraid not. The big flaw in President Obama’s health care reform, as everybody is now beginning to realize, is that it does almost nothing that would actually make health care less expensive. It concentrates on who pays for health care and on making it more widely available. There are some “across-the-board” spending cuts, to be sure. But an “across the board” cut with no more details amounts to saying, “Take care of this, won’t you?” It doesn’t say how.

Brill’s essay fits comfortably into two hoary sub-genres of health care reform journalism: One is, “Why does an aspirin cost $14.95 in the hospital when it’s 100 for $2.95 at Walgreen’s?” The other is, “Granny wants to die—why won’t they let her?” It’s a maddening combination.

The great strength of Brill’s essay is his revelation (or at least it was a revelation to me) that United States health care costs are not just high and rising. They are also almost totally arbitrary. What any individual patient pays for a particular service is all over the lot, although of course it is also very high. An evening in the emergency room with chest pains that turned out to be heartburn: $21,000. Eleven months of unsuccessful treatment with lung cancer, followed by death and a $900,000 bill left behind. And so on.

Brill has discovered something with the wonderful name of “Chargemaster,” that tells doctors and nurses how much their particular hospital charges for each service they provide. Brill is a little vague about the Chargemaster’s physical manifestation, but it’s basically a database that functions like those computer printouts glued to the side windows of cars in the dealer’s showroom. These printouts list what accessories the car comes with, and tell you how much they’re going to pretend it’s all going to cost the typical shmo. But for you….

If there is any pattern at all, it is a perverse one: Those insured by the government, mostly Medicare recipients, pay the least—including the government’s share—because the government has used its market power to negotiate low rates (although Congress, in its wisdom, has forbidden Medicare to do that for drugs). Those who are dependent on private insurance, lacking the government’s clout, pay a bit more. Those with no insurance, and no large public or private organization to negotiate on their behalf, pay the most.

A whole new profession is growing simply to guide people through the maze of insurance forms. It even has its own trade association: the Alliance of Claim Assistant Professionals. They typically charge $100 an hour.

Did you know that you’re supposed to negotiate your hospital bill? I didn’t. What looks like the bottom line on your incomprehensible statement is actually just a starting point. Hospitals expect to come down. And we’re not talking 10 percent or 20 percent. A typical hospital ends up getting paid barely a third of its ostensible bill, Brill says, while prestige palaces like Sloan Kettering in New York and MD Anderson in Houston typically settle for half off. Of course you have to know this to take advantage. Plenty of people pay the whole freight, not knowing that they’re supposed to be negotiating. Furthermore, it’s not exactly a fair fight. If you’ve just learned that you have cancer, or a child or a parent or a spouse does, you may not be at your sharpest.

The main reason health care prices in the United States are so high and rising is not primarily the aging of the population, or the constant discovery of expensive miracle cures, or the perverse insistence of doctors and nurses on keeping people alive whether the patient wants this or not. These are the usual suspects.

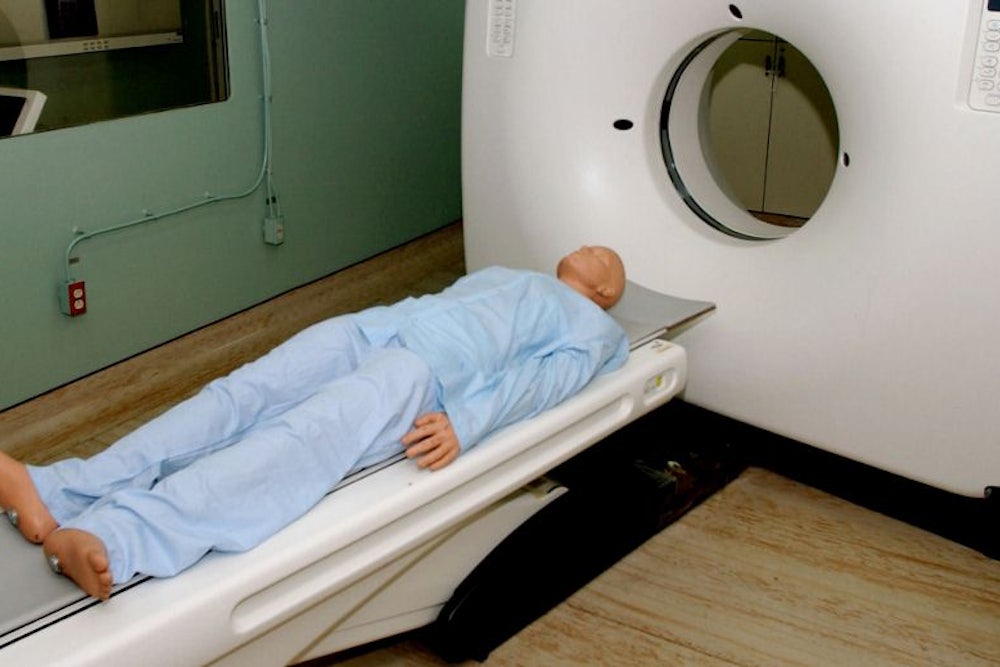

I’m usually a hard sell for arguments that we can’t expect market forces to work in this or that bit of the economy, and therefore we must subsidize it or protect it from competition. But Brill provides substantial evidence that the main reason for high and rising health care costs is precisely that free market forces don’t work in the health industry. The theory of free markets assumes that transactions are all at “arm’s length” and between equally informed actors. That is not how it works in health care. Consider a patient who is told he needs a CT scan. Compare that with a typical large decision in the competitive market, such as buying a car. Count the ways in which the basic assumptions of free-market capitalism don’t apply to the CT scan. I stopped at ten. (Some of what follows isn’t from Brill’s piece and he’s not responsible for it if he disagrees.)

First, the customer/patient has no way of evaluating whether he really needs a CT scan or not.

Second, the patient can’t shop around for the best price. You can’t just call a bunch of doctor’s offices, CT scan clinics and hospital radiation departments and compare prices. Generally they won’t even tell you how much they charge over the phone. And, as Brill demonstrates, the price they cite may be a fiction—or an opening bid—anyway.

Third, no one is looking for a bargain CT scan. When they’ve just found a lump, you’re not going to start quibbling over price.

Fourth, this is doubly true if—like most people—you do have some insurance. That means at least part of the cost will be paid by someone else.

Fifth, the decision maker—your doctor—is not going to pay anything. So he has no incentive to consider the price. Chances are he doesn’t even know the price.

Sixth, in fact he may well be owner of the CT scan equipment, or an investor in the CT scan clinic, to which he directs traffic. That gives him a strong bias in favor of using it. A lot.

Seventh, he may be getting payments from CT scan manufacturers. Many do. Perfectly legal and considered perfectly ethical, as long as the payments are revealed.

Eighth, defensive medicine: better for your doctor to have done an unnecessary CT scan than to find herself at the wrong end of a lawsuit. This is often discussed as a matter of ordering up needless tests, or prescribing expensive drugs when cheaper ones are available, performing worthless surgery, and so on. But the real problem is therapies that aren’t completely worthless, but are probably or almost completely worthless. Our health system has nobody to say, “enough,” in such situations, and thousands of hungry lawyers to say “more, more.”

Ninth, setting prices for pharmaceuticals brings special challenges. Suppose a pill for cancer costs $2 billion to develop and shepherd through the regulatory process, then costs only a dollar per tablet to manufacture. What is the correct price for it? Classical economics says that it’s the “marginal cost” of producing an extra pill—that is, a dollar. But the price must be at least the average cost per pill or the company will never recover its development costs, and future companies will have no incentive to develop new drugs. This is true, to some extent, of all products, but especially “new economy” products such as pharmaceuticals and software.

Tenth, the same forces that are driving up chief executive salaries in all industries are at work in pharmaceuticals and hospital administration. The CEO of Biogen made $7 million last year. Six officials of Sloan Kettering make over a million dollars each. The President of MD Anderson makes $1.8 million. The head of Montefiori Medical Center in the Bronx makes over $4 million. His CFO makes $3.2 million. The head of the dental department makes $1.8 milllion. Like the football coach, the president of a university hospital invariably makes more, sometimes multiples more, than the university’s president.

My own conclusion after reading Brill is that if Americans really don’t want a single-payer (ie, government-run) health care system, we can try half a dozen big reforms of the current system. Who knows? They might work. Give it five years and call me in the morning.