Our best TV shows may be more complex than ever, but our theory of their greatness has become utterly reductive: In this reputedly golden age of television, it all boils down to the showrunner, television’s own auteur.

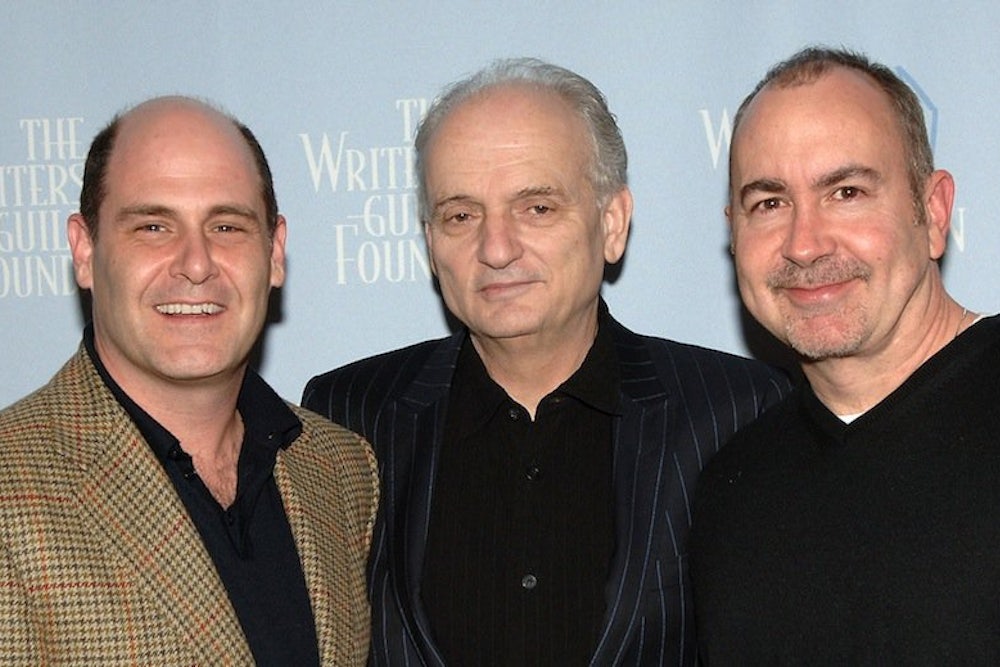

According to this theory, the villain is a clueless suit, sending along absurd notes; the hero is the courageous iconoclast, ready to fight the tiniest battle. Here’s one example from the set of “Mad Men,” recounted in Alan Sepinwall’s recent book, The Revolution Was Televised: The Cops, Crooks, Slingers, and Slayers Who Changed TV Drama Forever: A costume designer presented the perfect button-up dress for a love scene to showrunner Matthew Weiner. “Unzipping is sexier,” he replied—and off she went to find a new dress. Everyone seems to thrill at these stories of micromanaging prowess. It’s why novelists are trying to write cable pilots; why The Hollywood Reporter publishes its annual “Top 50 Power Showrunners”; and why, in 2010, no less an outlet than Cahiers du Cinéma—the French publication that popularized the original film version of auteur theory—put “Mad Men” on its cover. This narrative has been reinforced by long magazine profiles of David Chase (showrunner for “The Sopranos”), David Simon (“The Wire”), David Milch (“Deadwood”), Shonda Rimes (“Scandal”), Lena Dunham (“Girls”), Liz Meriwether (“New Girl”), and others.

But this obsession with showrunners—what we might call the showrunner fallacy—has obscured what makes television so great. In his (otherwise excellent) forthcoming book, Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution: From The Sopranos and The Wire to Mad Men and Breaking Bad, Brett Martin emerges as the latest exponent of this fallacy. Martin credits the shows in his subtitle, which, together, he labels TV’s “Third Golden Age,” to the showrunners themselves, with their “immense powers of rejection and benediction.” (Martin’s showrunner metaphors tend to be deific). Yet this approach prevents Martin from exploring the people and pressures that are unique to television—exactly what the medium’s reporters and critics should be working to understand. Instead, they praise or blame the showrunner, succumbing to a kind of narrative simplicity that we would never accept in an Emmy-winning drama.

Even before the word showrunner entered our cultural vocabulary, television was a writer’s medium. In its first Golden Age (the experimental 1950s), in its second (the network-drama-powered 1980s), and in all the lesser programming in between, television has depended on its scribes. Bruce Helford, who served as a showrunner on “Roseanne,” once framed that dependence like this: “Television is really bad art. It’s like someone going into a museum and saying, ‘We have a lot of blank walls, let’s make some paintings to fill them up.’” The cheapest (and fastest) way to do this was through writers churning out dialogue-heavy scripts.

Historically, as Martin explains, television’s other key player has been the producer, especially independent producers like Grant Tinker. It was Tinker who hired Steven Bochco to create “Hill Street Blues,” who then hired a dedicated staff (rather than a smattering of freelancers). Throughout the ’80s, more and more shows switched to the “writer room” model—and more and more head writers pulled double-duty as producers, taking control of their casts, their sets, their budgets, all of it. These folks would eventually become known as showrunners.

That didn’t mean that television’s creative types felt fulfilled. Yet. When a young staffer told David Chase (during his days as a network showrunner), “It’s not TV, it’s art,” Chase mocked the staffer. “You’re here for two things,” he told her. “Selling Buicks and making Americans feel cozy.”1 Slowly, however, Buick-buying America split into smaller and smaller niches. Hollywood abandoned its more mature audiences, and HBO began courting them with serious shows—and releasing those shows on DVD. Next came DVR, along with online message boards and exegetical recaps. Not all television was getting better. (CBS launched “Survivor” and “CSI” the year after “The Sopranos” premiered.) But some of it was, and cable channels realized that a smart show or two could make them stand out. Maybe it was art, after all.

Balancing this broader context with various shows and showrunners makes Difficult Men a sprawling book, but Martin proves to be a clever, versatile guide. He offers first-rate narrative journalism when he uncovers the story of James Gandolfini disappearing from “The Sopranos” set for days at a time. He gets terrific quotes. (When he tells Alan Ball, the “True Blood” showrunner, that Chase still grumbles about not directing films, Ball replies: “Go ask him, ‘Which films?’”). And he digs into the writers’ rooms, which he shows to be less a place than a process, where different writers hold different roles. On “The Wire,” George Pelecanos wrote each season’s penultimate episode. But when he complained that only 30 percent of his work was making it into the finished product, Simon, his showrunner, reminded him that was “pretty good.” As Frank Pierson, a veteran writer, puts it: “There’s a kind of psychoanalysis that goes on in that room, and that everybody on some level is helping you discover what the story is.”

Despite investigating these dynamics, Martin’s heart still belongs to the showrunners. At one point, he notes Chase’s affection for the powerful post-auteur directors of Europe. Yet those directors, Martin continues, “would have killed for a fraction of the godlike powers over an ever-expanding universe that [Chase] exercised from his office. … His name and its power were so often invoked, usually in whispers, that he came to seem like an un-seen, all-knowing deity.” With this level of power—and this sort of gushing description—it’s no surprise that many showrunners turn out to be narcissistic and cruel. Martin relates another, very different story about Weiner and a costume designer—this time on the set of “The Sopranos,” where Weiner browbeat the designer so mercilessly she began carrying a mini-cassette recorder to capture his attacks. Once, when a “Mad Men” staffer started talking about his pet, Wiener cut him off: “No one gives a shit about your dog.”

But there’s another (arguably larger) problem with the showrunner fallacy: It just doesn’t make sense, given how television gets made today. Consider a brief scene from “Justified,” the FX drama in which Timothy Olyphant plays a Kentucky-based U.S. Marshal. The camera starts on Olyphant, sitting in a backwoods barbecue, fidgeting with a saltshaker. Some local criminals arrive, and before long, everyone’s drawn a weapon—until, at the moment of maximum tension, the saltshaker, left half-cocked, topples over. It’s a great example of how “Justified” balances its black humor and rural realism with its noir-ish drive. It also had nothing to do with the series’ showrunner, Graham Yost. Olyphant, who is also a producer, thought up the scene, a writer wrote the first draft, and the episode’s director came up with the salt shaker. Yost inserted the moment early in the scene—until an editor suggested delaying its capsizing until the end. Most television takes shape in precisely this way, created less by celebrity chef than by crock pot.2

Even the suits can contribute to the shaping of a terrific show. On the pilot of “Battlestar Galactica,” a Cylon says, “God is love.” It was a throwaway line—the show’s allegorical interests centered on September 11—until a studio executive suggested that religious fundamentalism might be the perfect motivation for the Cylon army. Television may have its godlike creators, but the most interesting and essential parts—the real drama—comes not from the deities but from their followers and the institutions they raise up.

This seems especially true for television and its future. The medium’s cachet has never been higher, with TV-centric essays running in Harper’s and The New York Review of Books. Yet there are signs of stagnation, as well. “AMC [didn’t] need to worry about [“Mad Men”’s] ratings,” one executive tells Sepinwall in The Revolution Was Televised. “What AMC need[ed] is a show, a critically-acclaimed and audience-craved show that would make us undroppable to cable operators.” To reach that goal, AMC didn’t promote “Mad Men”’s period details or its gorgeous cast. Instead, it promoted a show from “an executive producer of ‘The Sopranos.’” And yet, now that it is undroppable, the channel has started to worry about ratings. AMC’s future isn’t “Mad Men.” It’s “The Walking Dead” and “Hell on Wheels,” two shows that possess a pulpier intent (and higher ratings)—and that have already fired a couple showrunners apiece.

Television’s showrunners, in short, may soon find themselves with less power. That’s all the more reason to adjust the way we write and think about their medium. Why not try to figure out how “The Wire” was able to produce a never-ending stream of memorable characters? Was it the writing? The casting? Or why not focus on John Toll, the talented cinematographer of “Breaking Bad”? In Martin's own book, there's a brief anecdote where Toll walks into an Albuquerque Circuit City and sees his show playing on the banks of bigscreen televisions. He proceeds to freak out at the employees over the televisions’ settings: “Do you realize how long I spend lighting these things?” he asks. But that’s the thing: we don’t.

Martin’s book abounds with this sort of amazing detail. Here’s another one: As Fred Savage’s Kevin approached high school, ABC considered installing Chase as the showrunner for “The Wonder Years.” Martin says Chase wrote a script that had Kevin “discover The Catcher in the Rye and start smoking cigarettes”—after which the network decided to pass.

I pieced together the scene’s genesis from interviews and the DVD commentary.