Reviewing Embryoyo by Dean Young, in 2005, Dean Young lamented that “in Mr. Young’s what seems zillionth slim volume of verse there is a seeming inability to take what is serious seriously.” But Young is perfectly serious about himself in his faux-review and used his pages in Poetry magazine to mock the sort of person who doesn’t like his poems. When he writes, “What abominable mixing we have in this monstrous tome,” he means that anyone who dislikes his aesthetic is probably a pompous, grandiloquent twit, the sort of rigid person who’d call collages like his “abominable” and plume herself for tacking on a synonym like “monstrous.”

At nearly sixty, Young is one of the most distinguished mid-career poets in America, known as much for his irreverence as his comedy. One critic pictured him in a leather jacket and clown shoes, and meant it as a compliment. Young, in mock-crotchetiness, described reading his own work as like “watching a clown burst into tears,” which of course he meant as an endorsement. His impression was as accurate as his critic’s, but neither is true as a compliment. The jacket and the shoes would signify coolness and silliness, not the careless edgelessness that leads to hundreds of jokes like the following: “You got to go way back, / to Memphis, like when Memphis was still / Egyptian.” This is less searing honesty than silly uncle. Young has an irritating habit of interrupting his prose with whatever joke comes to mind, no matter how unfunny or how unrelated it is to his subject. He also has the clown’s problem with sadness: when you cry after having never been clearly serious, your tears are disorienting.

Young has always been capable of more than humor and confusion, but he limits his emotional repertory to them by finding ways not to criticize himself. The tone-deaf jokes, the imprecise preciousness, the ironies and digressions, the incorrigible obliqueness—these are all ways for him to avoid any serious question except that of whether his work is worth reading. Digressions can avoid the questions at hand, irony can hide how you feel, and irreverence can hide what you value. Obliqueness can hide what you mean, and preciousness can hide, or suppress, your frustrations. In Young, this all makes for a kind of jester-like Ezra Pound. The sacred mixes with the profane, the new with the old, science with spirituality, sentiment with suspicion, birds with aquariums, bunnies with spaceships. His poems are pastiches, structured (or not) by his associations. And so the poems are always about the emotions that made him associate; and when these are glib they make the poems glib as well.

Young’s new book tells the story of how his emotions have grown more serious and considered, and how the resulting associations clarify the confusion of modern life rather than only perpetuate it. Unfortunately, its organization tells a different story. Bender, composed of new poems and others selected from his first ten collections, is structured by alphabet rather than chronology, without the names of the books the old poems came from, obscuring the fact that Young has over the last couple of years just begun to realize his potential consistently. Caprice became urgency, whimsy became wit. This time also saw the crucible of a medical condition dire enough to require a heart transplant, yet it is not crazy to think that the crisis helps to explain his success. He has always been a poet of associativeness whose strength and weakness was the range of his associations. It follows that his work would grow more profound and affecting when what came to his mind were not the complacencies of an endowed chair but matters of life and death.

The handful of poems that Bender includes from Young’s first book, Design with X, show a number of the tendencies that his later work moves away from. Everything is more direct. Images and scenes are sustained and even earnestly lyrical. His abstractions evoke what they describe more vividly than concrete terms plausibly could. Even a phrase as straightforward as “the delicate downward yearning of snow” shows us both the scene and the terms in which we may tend to feel it, thereby evoking both a perceptual field and an act of perceiving. Likewise the abstractions of “Casting Off” evoke the vague, middle-aged dread of the poem:

In a rowboat you can hear the other

boats knocking the pier like hollownesses

you hear waking in the dark, noises

of injured winds....

Hollownesses wake in the dark: the childlike animism sits in tension with the adult defeatism of the emotion, in which the boats knock the pier like something imagined but not substantively believed in, the dawning hollowness of adult imagination. The contrast recurs as that between a child’s abandon and an adult’s routine:

So for a while

you try to get to heaven and who knows?

Well, you come back a small, silly man

buying worms in delicatessen boxes....

The first sentence shows an adult imagining a child’s perspective, and the second, the reverse, perfectly expresses a child’s confusion before a man who is small not compared with himself but with his dreams for himself. (What is sillier to a child than keeping worms in delicatessen boxes, and who would say “delicatessen” besides a child still learning the names of things?) The linguistic tricks of the poem portray the conflict between the different versions of Young that survive in him.

This work is deft and not conventional by most standards, but it is sufficiently within the conventions of American poetry that readers could plausibly see its tropes as not Young’s own. The abstract, disordered Romanticism, the fluid, discordant perspectives—these are tokens of Ashbery, and Young’s rare poems about his personal life can sound like a kind of confessionalism. (“I’ve been looking at / a sad man’s photos of himself ... cock garishly haired,” he writes of his dead father.) Perhaps it was self-protectiveness, or the desire not to fall into any contemporary sub-genre, that drew him to an increasingly obfuscatory surrealism. The tropes grew less recognizable, but so did the emotional conflicts.

The results are poems that always stay a step ahead of themselves. His abstractions, rather than clarifying thoughts and emotions, read like jokes at the expense of a reader trying to understand anything:

I move the triangle

toward the furnace as indication of the indeterminacy

of all human affairs. There is no triangle, there is no

furnace.

His father resurfaces not as a cause for emotional openness, but as the subject of whimsy that the reader has no idea how seriously to take:

The last few months my father amassed a collection

of paperweights. He knew he was going to disappear.

And the juxtaposed perspectives grow so confusing and random that you lose any sense of the conflicts they embody, as in “The Oversight Committee,” whose conceit is that the arbiters of someone’s life are exploitative managers:

It has always been our intention

that your stay among us be but brief

even though we may have chased you

through the hallways, promised you

our chariot, turned you into echoes

and trees and stars. Oh how you glowed

by the water coolers. As regards

earlier memos re: orgasm cultivation,

that should have read orchid cultivation....

The earlier work shows how its conflicts call for complex expression, whereas in this case it seems that the complex form just occasions Young’s zaniness.

As the poems lose clear perspective and conflict, they stand out less as wholes than as isolated jokes. Some are compellingly silly (“First you’ll / fall in love with what you can’t / understand. The baby ram butts the shiny tractor.”). But many of his jokes are truly awful, such as his glib allusions to Hamlet (“to be or not to be, what’s the big diff?”), Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” (“time’s winged whatchamacallit / hurrying near”), and Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium” (“What form after death will we take, / a gizmo birdie like William Butler Yeats?”). His subject clearly has something to do with the juxtaposition of high-cultural allusion and contemporary idiocy, but without a clear structure the jokes don’t express a clear conflict. Except with themselves, that is: the jokes are odd enough that you’re never sure whether you’re reading Young’s bad jokes or his ironic take on bad jokes. You might begin to stop caring.

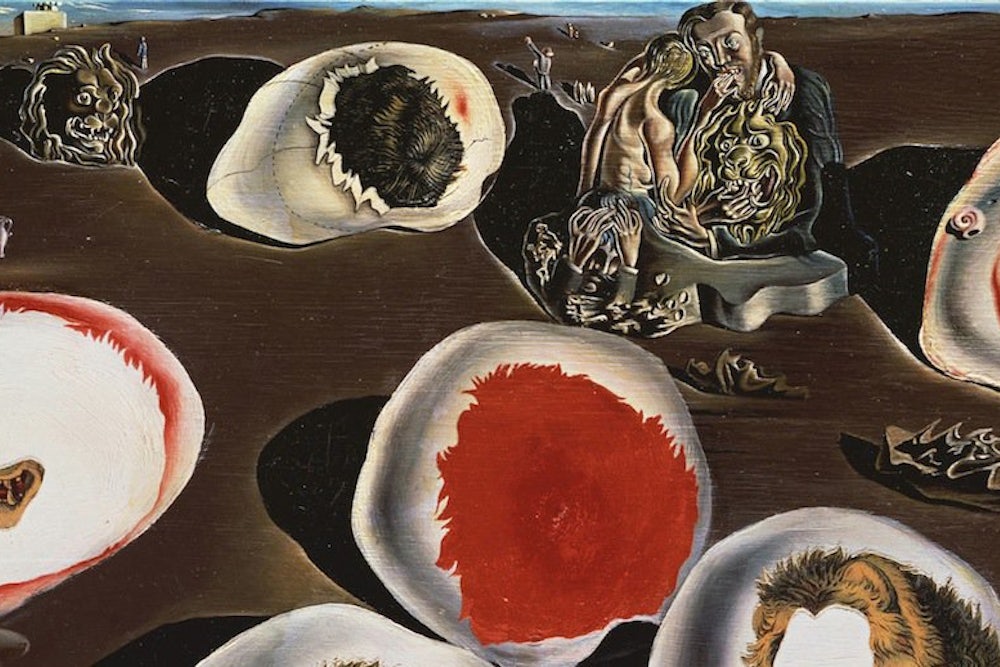

Young owes a lot to French Surrealism, with its dream logic, its lack of apparent ordering, its sense of triumph in the primitive. (Young has written more than once that “every third-grader is a Surrealist,” tempting his critics to say the reverse.) The classic problem with this kind of poetry is that its method rarely reaches its ambition. André Breton and the other party-line Surrealists thought that evoking their readers’ dream lives would emancipate their readers’ desires, which had been repressed (these Surrealists were also Marxists) by false consciousness. The reader would learn the wishes of her unrestricted unconscious—or “surconscious,” the unconscious free of all contradictions with itself and its world—and these wishes, when conscious, would reshape her world. Say what you will about the theory, but in practice the Surrealists’ associative or “automatic” writing sounded mostly like these lines of André Breton’s:

And a few flat drops

To warm up the kettle of musty flowers

At the foot of the staircase

Divine thought whose tile is star-studded with blue sky

The expression of bathers is a wolf’s death

Take me for your girl friend....

This looks to me the way I imagine poetry looks to people who hate it—opaque, self-indulgent, arbitrary, a variety of private writing: we all know how boring it is to hear about someone else’s dream. Surrealism’s attempt to escape the self by way of free association ironically results in the self-absorption of impulsive association unguided by deliberative care. The surrealist confidence in associations encourages in Young a kind of uncertainty, working by endless analogy rather than order or reason—a kind of fractal uncertainty, a thousand jokes and ironies that lead a reader to despair over a conversation that, for all its self-promotional whimsy, never really begins.

In April 2011, Young had a successful heart transplant after his degenerative heart condition, long bad, got worse. He also released his most emotionally vulnerable book in two decades. The poems in that collection, Fall Higher, fortify his old associativeness with a new sense of direction, spurred by a profound terror in the face of mortality. “The most misunderstood airplane / is a coffin.” That is not really a joke; the humor is the pathos in the absurd discrepancy between what he wants and how he goes about it, between his salvation and his poetry. Young has become self-critical, and much of his self-criticism shows itself not in this sort of explicit candor but in ways that his old habits serve deliberate ends.

Much of Fall Higher is morbid and precise. “Because I will die soon, I fall asleep / during the lecture on the ongoing / emergency.” Has his emergency started to bore him, or is he making fun of his dire self-absorption? This wicked pathos carries over to “Springtime for Snowman”:

I don’t understand the cicadas

in my throat, coal in my chest,

tiny mushrooms called death stars,

scar, scar, scar, all the current theories

declaring the end of meaning although

I don’t know what meaning means....

I find it hard not to feel for the snowman. This is because he sounds so much like Young—the scars, the metaphysics

of language, which Young often writes about vaguely; but empathy is also

provoked by how humanely Young shows

the snowman’s resolve in its dignified

meaninglessness:

No god? No sweat.

No hope? So what. I won’t let the ice

on my face be wasted, won’t mistake

its melting for tears.

The cosmic joke is not that the snowman is like us but that we are like the snowman, with even our noblest responses insignificant and fleeting in the face of death.

The counterpart of Young’s mordancy is a kind of fragile optimism, as though he needs all his energy to feel anything positive. He calls one of his poems “Optimistic Poem”—which has all the prescriptive force of “good first date”—and begins it, “You expected an affordable daydream / but got an unhinged psalm,” a description that fits his emotional abandon much more than his formal control. Some of these psalms are actually understated, such as “After My Own Heart,” in which Young imagines his wife after his death:

I like to think of you busy,

maybe washing parsley

and I am completely forgotten.

“Busy ... parsley”—an uneasy rhyme for an uneasy emotion, if a generous one. He wants her not to miss him but to hold on to a part of him, so he imagines a way in which that could be so:

Have you noticed how ants meet?

Their language single molecules exchanged,

that’s why they keep so clean.

They say Here and Hello.

They say Found and How far.

They touch each other all over.

His language touches her like an ant’s, down to the molecule of difference preventing “how far” and “over” from actually rhyming. But with this hope comes the unbridgeable gap between the contentment Young imagines for the ants and his obvious dread, an unease captured precisely in that same off-rhyme.

Young’s psalms become truly unhinged in the manic optimism of “Delphiniums in a Window Box,” whose very title sounds like abundance. The poem turns his distraction and diffuseness into an anxious affection too absorbed by his wife to even describe how he feels:

Every sunrise, sometimes strangers’ eyes.

Not necessarily swans, even crows,

even the evening fusillade of bats.

That place where the creek goes underground,

how many weeks before I see you again?….

Everyone says

Come to your senses, and I do, of you.

Every touch electric, every taste you,

every smell, even burning sugar, every

cry and laugh. Toothpicked samples

at the farmers’ market, every melon,

plum, I come undone, undone.

One expects to hear after “every melon, / plum” something like “I come undone” but not to hear the last word repeated, with which the rhythm, like the speaker, comes “undone.”

As Young became again more direct, personal, lyrical, more able to take what is serious seriously, it became easier to feel the contradictions in his work and with that easier to see how his conflicts call for the forms he expresses them in. His verse became more evocative, a trend that continues with the new poems in Bender. There is the occasional nonsense, such as “How to Be a Surrealist” (although I laughed at the first sentence, “Sleep well”). But most of his new poems look at themes from his transplant and its aftermath with the self-awareness that comes from investigating your habits. He has them follow from the drama of poems such as “The Rhythms Pronounce Themselves Then Vanish,” in which a series of increasingly random lines after he learns of his heart condition show his inability to deal directly with the news, ending with the mock-nihilism of “All information is useless.” (Useless perhaps for trying to comprehend your own death.) Similarly, his habit of yoking together heterogeneous associations finds its most precise and gorgeous form in “Restoration Ode”:

What tends toward orbit and return,

comets and melodies, robins and trash trucks

restore us. What would be an arrow, a dove

to pierce our hearts restore us. Restore us

minutes clustered like nursing baby bats

and minutes that are shards of glass. Mountains

that are vapor, mice living in cathedrals,

and the heft and lightness of snow restore us....

The poem not only shows us the rush of experience but, with its lyrical abstraction, clarifies that experience in its randomness and fragility:

And one more undestroyed, knocked-down nest

stitched with cellophane and dental floss,

one more gift to gently shake

and one more guess and one more chance.

Young could not have written this a decade ago or without the habits of his recent years. Readers of Bender will be happy to find that Young, in learning to doubt himself, has given us cause to believe in him.

Adam Plunkett is the assistant literary editor of The New Republic. Follow him on Twitter @adamfplunkett.