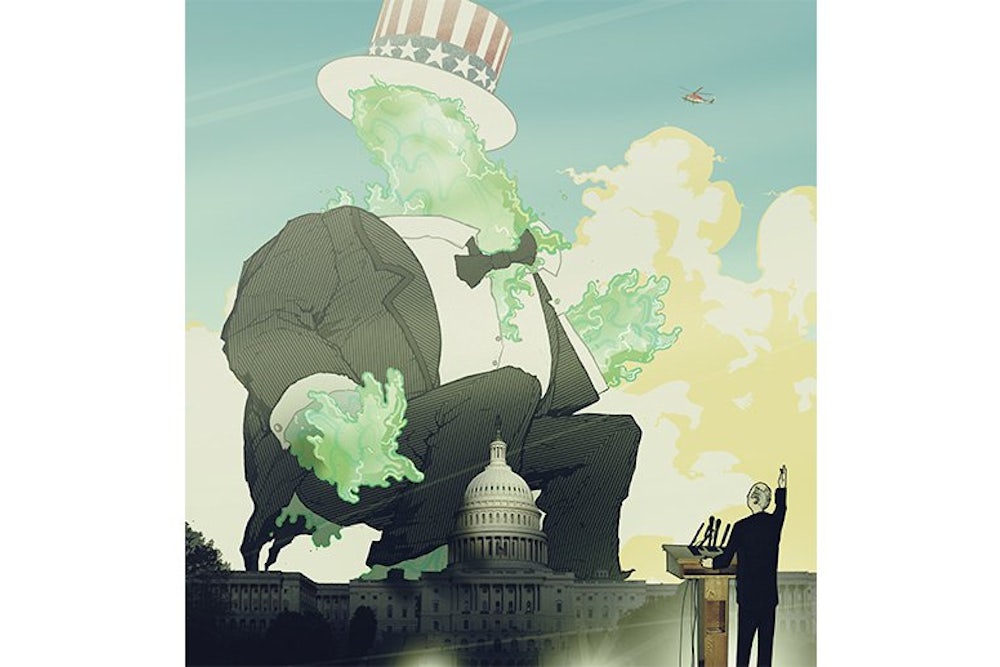

Americans believe that they have the world’s freest and best political system; it’s just the government and the people who run it that they despise. The scorn is particularly intense for Congress, and not without reason: political changes have undermined whatever dignity and respect members of Congress once had. While increased polarization prevents them from addressing urgent national problems, the rising cost of campaigns makes them more dependent than ever on fund-raising from donors with deep pockets. No wonder they appear to be ineffectual, money-grubbing, and submissive to special interests: the degraded image is just a by-product of the political circumstances of our time.

The financial crisis, the recession, and the anemic recovery have done nothing to dispel popular distrust. When it bailed out some of the nation’s biggest financial institutions after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the government may have staved off a total economic collapse, but it confirmed for many Americans that moneyed interests get help that ordinary citizens do not receive. Beyond the immediate emergency, the financial crisis also set up a critical test of governing capacity: could Congress and the incoming Obama administration take advantage of the crisis, defy cynical expectations, and adopt effective legislation to restore financial stability and prevent another meltdown? Both the new president and congressional leaders pledged to make that goal a high priority at a time when Democrats would have substantial majorities on Capitol Hill and public opinion surveys showed broad support for reining in Wall Street. But financial reform posed a difficult test for several reasons—the political power of the industry, the complexity of the issues, and the complicity of leading Democrats in the policies that helped to bring about the crisis.

Even among special interests, finance is special. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, which tracks political donations, “the financial sector is far and away the largest source of campaign contributions to federal candidates and parties.” Thanks in part to federal policy, finance has become the dominant sector of the economy, increasing its share of total domestic profits from 15 percent in the early 1980s to 41 percent in the early 2000s. The financialization of the economy promotes the financialization of politics, as money finds its way to power.1 The 2008 crisis made some new regulation likely, but the industry’s leaders were dead set against any changes they saw as threatening their profits, and they were prepared to spend heavily on lobbying and political contributions to ensure that wouldn’t happen.

The complexity of financial policy also encourages congressional deference to Wall Street. The ultimate basis of finance’s power is structural: if governments adopt policies that genuinely threaten financial markets, capital will migrate elsewhere, credit will tighten, and economic growth will suffer. But the more complicated the markets become, the more difficult it is to know where the danger point lies. Complexity amplifies the industry’s influence in discussions about alternatives, because its CEOs and lobbyists can make inflated claims of perilous repercussions from change that legislators do not know enough to discount. Technical complexity also limits countervailing public pressure to resist Wall Street’s demands.

Although Democrats saw the 2008 crisis as requiring new rules, the party’s leaders had championed financial deregulation during the 1990s and were eagerly and successfully competing with Republicans for the industry’s campaign contributions. In 1999, Bill Clinton and his economic advisers, as well as top Democrats in Congress, had supported the legislation repealing Glass-Steagall, the Depression-era law segregating commercial banks (and their federally insured deposits) from investment banking. “Removal of barriers to competition,” Clinton had declared on signing the repeal, “will enhance the stability of our financial services system.” Removing those barriers did exactly the opposite. Clinton had also signed legislation in 2000 barring any regulation of financial derivatives, which was the market that would be at the center of the crisis eight years later. In 1995, Senator Chris Dodd of Connecticut had even played a leading role in overcoming Clinton’s veto of legislation that fulfilled one item in the Republicans’ Contract with America by making it more difficult to prove private securities fraud. A longtime booster of Wall Street who became chair of the Senate Banking Committee in 2007, Dodd would have a critical role in financial reform after the crisis. And Barack Obama brought back to the top ranks of economic policy-making the very people who had advised Clinton to support financial deregulation.

While other recent books have dissected the Obama administration’s response to the economic crisis, three new books focus on Congress and present the battle over financial reform as a case study with general lessons about American politics. The books treat many of the same events and deal with the same basic problem of democracy versus the power of finance, but they approach the story from entirely different angles. Robert Kaiser’s Act of Congress is a step-by-step, journalistic narrative of the legislative process from the eruption of the financial crisis in September 2008 through the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in July 2010. In Kaiser’s telling, Congress overcame special-interest pressures and partisan obstruction, worked through complex issues, and enacted substantial and intelligent legislation. In stark contrast, Jeff Connaughton’s The Payoff is a burn-all-bridges memoir of a longtime lobbyist who became a top aide to a liberal Democratic senator and says that Dodd-Frank was shot through with holes as a result of special- interest pressures and the connivance of both Dodd and the administration. And in the most weighty and analytical of the books, Political Bubbles, the political scientists Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal argue that 2008 was a “wasted crisis” because American democracy failed not only in the run-up to the bailouts, but also in the aftermath. Dodd-Frank, they say, exemplifies a long historical pattern (except for the New Deal) of weak and often counterproductive governmental responses to breakdowns in the financial system.

To those who believe in the honor of the legislative craft, Kaiser’s book will come as welcome relief from the steady stream of television and movie portrayals of Congress as a snake pit of vanity and corruption. A veteran Washington Post reporter, Kaiser enjoyed exceptional access to the two central figures in the real-life drama of financial reform, Barney Frank and Chris Dodd, as well as to their aides and influential lobbyists. The result is an inside-the-Capitol narrative that largely reflects the viewpoint of its protagonists. As the author of an earlier book on lobbying, Kaiser is under no illusions about the purity of congressional politics: Congress, he says, is a “broken” institution. But the gist of his book is that, despite everything that is wrong with it, Congress succeeded in passing a landmark reform, thanks mainly to two legislators who put governing ahead of politics in what was, for each of them, the culminating achievement of a long political career.

Different though they are in skills and personality, Frank and Dodd shared, according to Kaiser, the practical wisdom required to get things done. Frank, who became chair of the Financial Services Committee in 2007 after serving in the House for twenty-six years, emerges as brilliant, conscientious, and deft in dealing with his fellow representatives. Known publicly for his barbed wit, he enjoyed wide respect among his colleagues for his mastery of the technical details of financial regulation. (“I’ve learned an enormous amount of things I never wanted to know,” he tells Kaiser.) If there is one surprise in Kaiser’s portrait, it is that Frank was entirely consumed with the “inside” game. “Mobilizing public opinion against rapacious bankers and lax regulators was not a priority for him,” Kaiser writes. “He had low expectations for the role of public opinion, especially on complex issues.” Although attentive to the concerns of liberal Democrats, Frank had no interest in tilting at windmills; he accepted the framework of the bill developed by the Obama administration, adjusting it in particulars, often to keep his party united. Relentlessly practical, he made sure the bill would pass.

“Dodd’s personal attributes were even more important,” Kaiser writes. Not as brilliant as Frank but “bright enough,” Dodd was popular with other senators and shrewd in dealing with them, always looking for ways to address the “substantive concerns of his colleagues, especially Republicans.” In a memorable episode, Kaiser recounts that at the Banking Committee’s first meeting on the bill, Dodd ignored a diatribe by the ranking Republican, Richard Shelby of Alabama, and then paired up Republican committee members with Democrats to work on specific issues of concern to them. The unsavory aspects of Dodd’s career get only passing mention—the senator benefited from financial favors that when exposed in the media led him to announce that he wouldn’t run for reelection; but as Kaiser tells it, Dodd’s retirement happily served the public good by enabling him to focus his energies on financial reform.

If all you want to know is how Congress passed the bill it passed, Kaiser’s book has the story. In the House, for example, where Democrats had a big majority, Frank’s problem was not to win over Republicans but to maintain significant support from his own party’s centrist Blue Dogs. A key step in that process, according to Kaiser, was a deal that Frank struck in private with the Independent Community Bankers of America, the trade group representing small “hometown” banks that have influence in every congressional district. Frank agreed to two concessions: a limit on the supervisory authority of the new agency that the law would establish to protect consumers, and a change in the formula for assessments paid to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which would shift more than $1 billion in annual fees from the community banks to the big banks. Wall Street would not like it, but by peeling off the hometown banks, Frank reduced local pressure on the Blue Dogs and other representatives to oppose the bill.

Stories such as these are instructive, up to a point; they tell us about overt conflicts in the legislative process. But Kaiser’s book has little to say about the law’s general framework or about ideas for reform that did not enter into the main congressional negotiations. Financial reform itself isn’t Kaiser’s interest; as its title indicates, Act of Congress is a case study in the legislative process, as if that case could be understood and evaluated apart from the substance of what Congress did. And even as a study of power in Washington, the book misses a lot. Social scientists distinguish among three dimensions of power. Who wins and who loses in overt conflict is only the first dimension. The second dimension is control, often implicit, over what gets on the agenda and the issues and alternatives that never even come up for discussion. The third dimension involves the terms of debate, the ways of thinking about problems.2 Kaiser’s book doesn’t go beyond the first.

At the level of overt conflict, the big financial institutions clearly did not always get their way in Dodd-Frank. The industry opposed the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau created under the law as well as other provisions, such as a watered-down version of the Volcker Rule (limiting the ability of banks to trade on their own account). Kaiser quotes Frank as saying at the end that “the big banks got nothing.” But there is more to the story, especially if we step back and consider the limits of the congressional agenda and the terms of debate.

Connaughton’s The Payoff explains how marginalized liberals in Congress would have expanded the agenda of financial reform and written legislation to reduce the likelihood that a few too-big-to-fail banks could again threaten to bring down the entire economy and give the government no choice except to save them. Like Kaiser, Connaughton provides a view of the legislative process from the inside—he worked in the Senate at the time—but he is harshly critical not only of Dodd-Frank but also of the Obama administration’s failure to undertake criminal prosecutions of financial fraud. The message of his book is that Democratic leaders in Congress as well as the administration were so deeply compromised by their ties to Wall Street as to be incapable of acting effectively on the people’s behalf.

The Payoff is partly a memoir of disillusionment and regret, partly an angry jeremiad. Connaughton began his Washington career as a “Biden guy.”3 After receiving an MBA from the University of Chicago, he abandoned an early career in finance to work for Joe Biden’s abortive presidential campaign in 1987 and then in his Senate office, leaving to get a law degree from Stanford. Returning to Washington in the Clinton years, he worked briefly in the White House counsel’s office and in private practice before joining with Jack Quinn, Clinton’s former counsel, and Ed Gillespie, the former chair of the Republican National Committee, to form the powerhouse lobbying firm QGA.

In his twelve years at QGA, Connaughton made a pile of money and acquired the experience that enables him to write a scorching analysis of “The Blob,” the term he says some insiders use to describe both the government officials that regulate finance and “the army of Wall Street representatives and lobbyists that continuously surrounds and permeates them.” After the 2008 election, disqualified by his own lobbying history from working in the Obama administration, he took a job as a top aide to Senator Ted Kaufman of Delaware, who had been named to serve for the remainder of Biden’s term. For two years, Connaughton helped Kaufman to take on Wall Street, but as he well knew, “when you take on Wall Street in Washington, you take on The Blob,” and your chances of winning are not good.

One of Kaufman’s concerns was to prod the Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission to prosecute financial fraud, but despite repeated assurances that inquiries were under way, no indictments were forthcoming. According to Connaughton, while the evidence for criminal prosecutions was clear, the administration gave the effort no leadership or priority. The excuse that prosecutions would damage the economy is implausible, Connaughton maintains: “Individual executives, not the firms for which they worked, could’ve been singled out and prosecuted without disrupting the banks’ ability to recover.” Instead of criminal prosecutions, the government brought civil cases that were settled out of court for what were often the equivalent of “parking- ticket fines” for the banks.

Although Kaufman served on the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, he was not a member of the Banking Committee and consequently had no role in shaping Dodd’s bill. In fact, Connaughton observes, while the Blob on K Street was kept well informed by “multiple leakers” from the Banking Committee, senators who were not on the committee were left “in the dark.” Dodd, whom Connaughton describes as “Machiavellian,” readily made concessions to Republicans who were not going to vote for the bill, while ignoring his own Democratic colleagues. “Dodd and the Treasury Department wanted a squishy bill,” Connaughton writes, “and the Republicans were willing to work with Dodd to weaken it.” When Dodd’s bill was voted out of committee, Kaufman delivered what Connaughton describes as a “withering critique.” The bill relied too much on regulatory discretion, provided “only a reshuffled set of regulatory powers that already exist,” and failed to undo the key deregulatory measures that brought on the financial crisis. Dodd’s response was to leave a voice mail for Kaufman: “Stop saying bad things about my bill.”

Kaufman’s alternative, as Connaughton describes it, was to establish clear statutory lines placing “strict limits on the size, leverage, and trading activities of the behemoth financial institutions.” An amendment to Dodd-Frank that Kaufman co-sponsored with Sherrod Brown of Ohio would have imposed such limits and therefore required a breakup of the mega-banks; it was defeated on the Senate floor by an almost two-to-one margin. In the view of Kaufman and other liberals, only structural reforms to the industry could resolve Wall Street’s conflicts of interest, protect ordinary investors, and prevent the behemoths from undertaking risky gambles in which they stood to win big if their bets paid off and the taxpayers stood to lose if they didn’t. Kaufman also wanted Congress to deal with a variety of issues such as high-frequency trading that the law did not address. Did the big banks, as Frank said, get “nothing”? In fact, they escaped any structural change. They have been able to continue doing business almost as if nothing had happened.

In Political Bubbles, McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal come to similar conclusions about financial reform as Connaughton and Kaufman. “We favor a strong set of simple rules rather than regulatory discretion,” they write. “The thirty-seven pages of Glass-Steagall are much to be preferred to the nearly three thousand pages of Dodd-Frank.” But they take a different approach to explaining the congressional politics of financial reform. Unlike those who write about Congress from the inside and highlight individual personalities, the political scientists put their emphasis on more general forces. Their argument is that the interplay of ideology, institutions, and interests results in characteristic failures of democratic government in handling financial crises.

According to McCarty and his co-authors, the United States has exhibited a historical pattern dating back to the nineteenth century of political bubbles inflating financial bubbles. By a “political bubble,” they mean “a set of policy biases that foster and amplify the market behaviors that generate financial crises.... During a financial bubble, when regulations should be strengthened, the political bubble relaxes them. When investors should hold more capital and reduce leverage, the political bubble allows the opposite.” And when the financial bubble ultimately bursts, the political response is limited and slow, typically depending on a change in power. In the one (partial) exception to the rule, the Great Crash in 1929 set in motion a belated but big enough shift in power and ideology to bring about a strong, structural response. Not only did Congress pass Glass-Steagall, which established government insurance of bank deposits as well as the separation of commercial and investment banking; the federal government (and the states) also provided significant debt relief to small borrowers, including both farmers and homeowners.

But “times have indeed been different” since the New Deal, McCarty and his co- authors argue, because the “opponents of change” have “succeeded in limiting the legislative response to a crisis.” That was the case after the savings-and-loan crisis in the 1980s, which resulted in the creation of a weak regulatory agency, the now-defunct Office of Thrift Supervision. That has also been true in the recent crisis, when “Washington rushed to bail out the commercial and investment banks and American International Group (AIG), but did little to relieve small debtors” and Congress passed Dodd-Frank, which “leaves ample opportunities for future bubbles.”

The principal forces that have limited the government’s response to the recent financial crisis are hardly mysterious. Ideologically, the crucial change has been the rise of free-market conservatism—“the belief structure,” as McCarty and his co-authors describe it, “most conducive to supporting political bubbles.” Institutionally, the key development has been the increased use of the filibuster in the Senate. Together, the growth in ideological polarization in Congress and the exploitation of institutional choke points have led to gridlock, blocking legislative adjustment of policies as conditions change. And in the case of finance, that failure to update policy has effectively meant deregulation, because of the creation in recent decades of new financial products not envisioned under the New Deal regulatory regime.

Finance-friendly government has also resulted from the industry’s increased lobbying and political contributions in an environment where countervailing pressure from consumer groups is negligible. Even in the latest battle, the imbalance has been staggering. According to Kaiser, a consumer coalition in 2009 announced it would raise $5 million to support financial reform; in comparison, the lobbying expenditures by the finance industry in 2009 and 2010 totaled around $750 million. Wall Street political contributions, McCarty and his co-authors point out, have gone to both Democrats and Republicans, though not indiscriminately. “The more conservative wing of each party (moderate Democrats and conservative Republicans) garners substantially more contributions than the more liberal factions.” The finance industry is bipartisan in the sense that it pushes both parties to the right.

In their analysis of Congress, McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal draw on their extensive prior work on congressional voting. That work shows that regional and other influences matter much less today than in the past; votes follow ideological positions in a pattern characterized by sharply increased polarization (less bunching of representatives in the ideological center). The upshot of this analysis is that, even when Democrats are in power, the most liberal bill that Congress can pass depends on the position of what they call the “veto pivot.” In the Senate, due to the filibuster, the pivot for the Democrats is the senator who is sixtieth from the liberal end of the ideological spectrum. When Dodd-Frank came to a vote, the pivot proved to be Scott Brown. (Democrats needed Brown’s vote because one seat was vacant after Robert Byrd’s death and one liberal, Russ Feingold, refused to vote for the bill.) Under these circumstances, Dodd’s conciliatory stance toward the Republicans makes perfect sense, not because he was able to persuade the Republicans on his committee to vote for the bill, but because it was clear that in the end the bill would have to be acceptable to a moderate Republican pivot, no matter whom that proved to be.

The same logic applies to the efforts that Max Baucus, as chair of the Senate Finance Committee, made to conciliate Republicans on health-care reform in 2009. Many liberals were furious about the concessions that Baucus made and the time he took in those negotiations. But even though none of the Republicans voted for the bill on the Senate floor, the efforts to conciliate them proved critical in winning over the most conservative members of the Democratic caucus, Ben Nelson and Joe Lieberman, who were the pivots for the Affordable Care Act.

The analogy between Dodd-Frank and the Affordable Care Act, the two major legislative achievements of Obama’s first term, works in other ways as well. Both are highly complex laws that the public has difficulty understanding. Both include important benefits for consumers: Dodd-Frank’s establishment of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the ACA’s insurance reforms and expansion of coverage. As a result of those provisions, I wouldn’t say that Dodd-Frank was a “waste” of a crisis or that the ACA was a mistake—but both laws leave key interests undisturbed and therefore do not deal with critical problems in either finance or health care. These similarities stem from the same underlying realities in Obama’s first two years. The Democrats were able to overcome deep ideological resistance and institutional obstacles in Congress only by making major concessions to interest groups in the general design of reform and to congressional pivots in the final details.

Yet the battles over financial reform and health care differed in at least one way. Financial reform never had the public’s attention the way health care did. According to McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal, “it was not because the public was divided, even along partisan lines, over the causes of the crisis or the need to reregulate the financial services industry.” In their view, skepticism about government’s ability to restrain Wall Street and confusion about what ought to be done dampened public engagement.

But there is another explanation for the negligible role that public opinion played in financial reform. During the debate over Dodd-Frank, neither Obama nor congressional leaders even tried to arouse public concern about Wall Street and build support for a stronger bill. Ironically, anger over Wall Street and the bailouts found its expression in the Tea Party in 2010. The Democrats began to stir that pot only in the wake of Occupy Wall Street, when Obama’s campaign was gearing up to fight Mitt Romney. Even then, as Cory Booker’s reaction to anti-Romney ads illustrated, many Democrats didn’t have any desire to take on Wall Street.

But wouldn’t it have been better to engage the public in the cause of financial reform in Obama’s first two years, channeling in a positive way the energies that went instead into the Tea Party and the Occupy movement? Yes, Democrats had benefited from Wall Street’s money, but (to paraphrase Fiorello LaGuardia4) monumental ingratitude is the first requirement of public service. And close behind ingratitude on the list of rarely mentioned demands of leadership is a lively sense of outrage. For those who may have lost that sense, a short journey into the literature on the financial crisis may be a healthy restorative. Connaughton’s memoir is a reminder about such deceptions as Goldman Sachs’s sale of derivatives to customers who didn’t know that those derivatives had been designed to go bust, and Lehman’s shift of liabilities off its balance sheets before it went broke, and the tower of speculation built on liar loans and other subprime mortgages. Millions of people have lost their homes, whole communities have been devastated, but somehow the government does not have the ability or the will to prosecute the executives responsible for abuses that contributed to these disasters.

This history is not over—we are still living it, and we may someday be reliving the worst of it. Channeling Ronald Reagan, McCarty and his colleagues ask: “Are you better off than you were before financial markets were deregulated?” Today the finance industry is more concentrated than it was before the 2008 crisis, and it is leveraged to the hilt. In The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to Do about It, Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig argue that the mega-banks’ excessive leverage is a continuing threat to financial stability. According to Admati and Hellwig, the debts of the five biggest banks in the United States as of March 2012 totaled $8 trillion, a figure that they say would have been higher under European accounting standards. They want to see stronger capital requirements, forcing the banks to raise a larger share of their funds in the form of equity so as to be more resilient in the face of losses. As the banks are now set up, Admati and Hellwig argue, they may not only be too big to fail—they may also be too big to save. The mechanisms set up by Dodd-Frank to deal with an emergency may be unworkable. We must hope that this is not so. After all, in the last crisis, at least the government did prevent a total collapse. In the next one, things could be worse.

Paul Starr is professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University and the author, most recently, of Remedy and Reaction: The Peculiar American Struggle Over Health Care Reform (Yale University Press).

This is sometimes referred to as the hydraulic theory of money and politics, though I don’t mean to endorse the idea that money will always find its way around campaign-finance laws no matter how they’re written.

The general idea of a third dimension of power comes from Steven Lukes; the relevant concept in this connection is what Willem Buiter calls the “cognitive capture” of financial regulation.

Readers of George Packer will recognize Connaughton from a profile in The New Yorker and Packer’s new book, The Unwinding.

“My first qualification for mayor of the city of New York is my monumental ingratitude to each and all of you,” LaGuardia declared on the night of his first election as mayor.