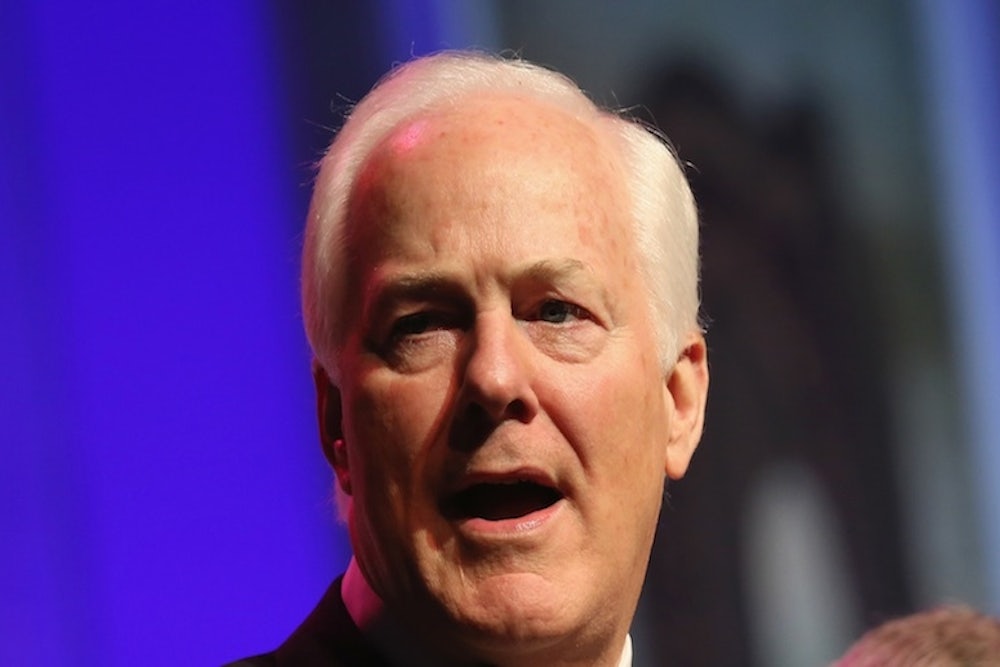

Over the years, Americans have gotten to know a few different politicians residing inside the sober, vanilla body known as John Cornyn. There was Main Street Cornyn, whose Chamber of Commerce politics made him a reliable ally to business during his Texas Supreme Court years. Then there was George W. Cornyn, who became state attorney general with Karl Rove’s help and then returned the favor with faithful water-carrying once he followed the fourty-third president to Washington. More recently, there’s been Ted Cruz Cornyn, the improbable acolyte of the hard-right newcomer. Observers say that despite his classically establishmentarian appearance, he’s thrown himself into the tea party act with characteristic skill—voting in sync with Cruz after the junior senator dinged Cornyn for supporting a fiscal-cliff-averting tax increase; joining Cruz in railing against the nomination of John Kerry for Secretary of State; and becoming an early antagonist of Chuck Hagel’s nomination.

The arithmetic is obvious: Cornyn is up for reelection in 2014 and doesn’t want to join the other former GOP pillars who’ve been toppled by the radical right. Bring on the red meat.

The more apposite culinary metaphor for Cornyn, though, is one passed along by a Texas strategist who likens Cornyn to butter—he soaks up all the flavors around him. The ur-factor of his three decades in politics is his willingness to zig and zag within conservative culture, amassing more institutional power with every zig, and always retaining his placid public image. But now it seems the tea party may have taken him one evolutionary step too far. In making a show of his fringiness, Cornyn may have lost his ability to horse trade over the things that matter to the Chamber of Commerce man who lies underneath all of the Senator’s various incarnations. And that’s been especially clear in the immigration debate that culminated in the Senate on Thursday.

In the 1980s, at the outset of his career, Cornyn was a lawyer who disdained the “good-old-boys system” he saw among his fellow attorneys. He won a seat on the Texas Supreme Court and gained a reputation as a friend of the state’s tort reformers. But his most impactful decision was his most unpopular with some Republicans—upholding a “Robin Hood law” that redistributed tax dollars from wealthier school districts to poorer ones. The ruling, in favor of a law that Cornyn said he personally disagreed with, clarified Cornyn’s reputation as a centrist, letter-of-the-law man at a time when Republicans were not quite Texas’s dominant party. And it also spared then-Governor Bush the mortification of raising taxes while considering a run for president.

Bushland noticed. In 1998, with a presidential run very much on the agenda, Karl Rove was seeking an attorney general candidate to challenge a Christian extremist in the GOP primary. Sober, boring Cornyn fit the bill. The ascendance of Rove-ian politics naturally demanded a political adjustment from Cornyn, one he would make with alacrity. Per the Houston Chronicle’s coverage of the race, Cornyn’s initial strategy was to downplay the role that Law and Order-style crime fighting would play in his job, focusing his campaign instead on the drier duties of an AG, like watchdogging parents who dodge child support payments. But after receiving a string of mild attack ads, according to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Cornyn began accusing his primary adversary of being a “sleazy” glory-seeker and resume fabricator, and labeled his general election opponent, a “junkyard dog.” He won convincingly.

As attorney general, Cornyn remained a guy without much televisual verve—even today, no matter how fringy his politics may grow, he can’t seem to muster the fieriness to go with them—but, again, the exterior sobriety masked the political adjustments. The silver-haired insider was now creating headline-making “10 most wanted” list of the state’s biggest deadbeat parents. He assailed a group of trial attorneys he felt the state had overcompensated to sue tobacco companies; he later expanded that crusade to investigate whether his Democratic predecessor had allowed a crony to get in on the action.

His ambition, thus broadcast, meant that Cornyn was not the attorney general for long. With his personal support and that of his fundraising network, Bush ensured Cornyn a path to the seat vacated in 2002 by Phil Gramm. Perhaps as repayment, Cornyn turned into a smiling foot soldier of the Rove-prosecuted culture wars. “Corndog,” as the president nicknamed him, stumped for constitutional bans on same sex marriage and flag-burning, and served as the mouthpiece for the administration’s rationale against releasing the Abu Ghraib torture memos—the latter an issue with which no other Republican senator had been willing to associate. But even as he took on yet another new set of issues, his style remained steady. As Michael Crowley observed for The New Republic, not acting like Rick Santorum had helped him to cut the line for several distinguished committee chair assignment.

Even then, the balancing act required to be at once a mature statesman and a senator who held hearings on the “homosexual agenda” was a tenuous one; it wasn’t hard to imagine circumstances under which it might fall apart. Paul Burka described how that might look in the Texas Monthly in 2007: “If he persists in the role he's carved out for himself, as a lieutenant in the partisan wars, he may find himself excluded from the closed-door bipartisan meetings in which policy is hashed out. On the other hand, he could always go back to being the kind of politician he was in Texas—the kind who would have been welcome in those meetings.”

That moment may have arrived. In his years as a Bush loyalist, Cornyn rarely had to choose between a seat at the table and the GOP’s overarching strain of conservatism. Ditto his first few years in the Senate’s Obama-era minority, when Cornyn passed his time with lonely crusades against appropriations for the Justice, Commerce, and Education Departments. None of those things endangered his serious Senator reputation.

But with the rise of the tea party, Cornyn has finally overextended his chameleon capabilities. It's tough, right now, to be both a right-winger and serious Senator. Nothing better demonstrates this than the failure, last week, of an amendment Cornyn offered to the Gang of Eight’s immigration bill. On its face, the measure was written like a love-letter to border wingnuts. It called for the addition of 5,000 new border guards, which no one but the Joe Arpaios of the world were calling for, and it conditioned the path to citizenship on a 90 percent apprehension rate at the border. But—in keeping with his Main Street roots—it also contained $1 billion to modernize ports of entry along the U.S.-Mexico border, an enormous slab of pork for businesses in a state where trade with Mexico is vital to the economy. It was just the sort of goody that the number two in the GOP should be able to offer his Main Street donor base.

In the short run, perhaps unsurprisingly, the effort failed: Fellow senators saw it as a sneaky attempt to poison the Gang of Eight bill; the tag team of John McCain and Chuck Schumer torpedoed his amendment with strong denunciations on the Senate floor. In the slightly longer run, though, a funny thing happened: Cornyn won on the gimmicky, kabuki theater part of his proposal, lost on the business-friendly, back-scratching part of it, and did nothing to advance his reputation as a Senatorial heavyweight. A few days later, members accepted an even more strident border security increase that increased border patrols by 20,000. But he proved powerless to demand the things that the business community—the constituents who are far dearer to him and his campaign coffers—wanted: Home-state pork.

On Thursday, Cornyn joined 31 Republicans in voting "no" against the Senate version of immigration reform. Yet the old, establishmentarian Cornyn still has a chance to make his comeback. “I would say, Cornyn is not dead yet,” said Simon Rosenberg, an immigration reform advocate with the liberal NDN think tank. Given the state he represents, Rosenberg said, and his expertise—well-hidden from the tea party, for now—on weedy immigration issues like port-of-entry, the senator is a natural choice for the conference committee that will resolve difference between the House and Senate immigration bills later this year. (Or, like as not, produce a bill that looks suspiciously similar to the Senate’s.) The Gang of Eight bill already allocates some resources for rehabbing U.S.-Mexico trade hubs, a goody the drafters are thought to have included with Cornyn’s cooperation in mind. But if the rest of the party leadership extends to him a committee seat—his best chance of affecting the most significant legislation to hit Texas in his whole career—Cornyn will no longer be able to follow Cruz in making self-evidently crazy claims about immigration reform.1 In fact, he might have to oppose him outright. The last time a conference committee took up legislation Cruz despised—the federal budget, in May—he and a handful of other true believers tried to block Senate leadership from appointing conference committee members.

And that is where Cornyn is today—staring, for his first time as a pol, at a situation that defies his attempts to be a serious Senator and an embodiment of the rightwing zeitgeist all at once. Lucky for him, whichever path he chooses, he has the chops to make it work. As USA Today quipped at the start of his Senate career, Cornyn is “a casting director’s dream.”

Molly Redden is a staff writer for The New Republic. Follow her on Twitter @mtredden.

While Cornyn was suffering the defeat of his amendment, the junior senator was entreating the Senate to reject the whole bill, because it perpetuates a system in which drug dealers leave women and children in the desert to die. And two weeks ago, Cruz didn't even vote to release the immigration bill to the Senate floor for debate, as Cornyn did.