Any contemporary author who decides to write a book about John F. Kennedy better have a damn good reason. Library floors buckle under the weight of volumes about his youth, his war exploits, his political career, the accomplishments and flaws of his presidency, his affairs, his marriage, his image, and his assassination—not to mention the photo collections and memoirs by everyone from his chief speechwriter to his kennel keeper. Amazon lists close to 40,000 books with either “JFK” or his full name in the title—not including most of the ones about his father, his mother, his wife, his children, or his eight siblings. With the fiftieth anniversary of that miserable day in Dallas almost upon us, there will soon be hundreds more.

One might salute Penguin Press for getting Thurston Clarke’s book into print and pixels ahead of all, or at least most, of the other entries in this peculiar half-century observance. Unfortunately, no other cause to applaud JFK’s Last Hundred Days: The Transformation of a Man and the Emergence of a Great President comes to mind.

Clarke, a prolific author of journalistic histories, has produced one of the least original works on John Kennedy’s life and politics I have ever read. He recycles most of his quotations, anecdotes, and judgments from the bottomless storehouse of Kennedyana, frequently straying from his “last 100 days” framework to tell us again about the PT-109 commanded by Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, father Joe’s fierce ambitions for his sons, JFK’s condescending treatment of Lyndon Johnson, and other chestnuts of the genre. For decades, thoughtful historians have debated such big questions as whether Kennedy would have sent combat troops to Vietnam and how committed he was to reaching détente with Fidel Castro. On each controversy, Clarke simply musters JFK’s most peace-minded quotes and evidently believes that settles the matter.

He also has a fondness for the kind of dramatic tropes common in soap operas and mediocre detective novels. Knowing that readers will have November 22 in mind as they flip through the pages, Clarke drops foreboding tidbits along the narrative trail. Kennedy tells one journalist, “Anyone who wants to exchange his life for mine can take it. They just can’t protect [me] that much.” He confides to his old college roommate that he would like to die a quick death, instead of wasting away like his father, a stroke victim. “Oh, a gun. You never know what hit you. A gunshot is the perfect way.” After a trip to Florida, he tells a close aide, “Thank God nobody wanted to kill me today” and then muses that, if anyone did, a motorcade would provide the best opportunity. Such lines deliver a mild shock, but Clarke shows no curiosity about their historical context. Was Kennedy more given to such morbid reflections than were other modern presidents? Assassins had also tried to kill FDR and Truman—the Democrats who had most recently held the office. So it would not be surprising if JFK reflected about the possibility that he would be a target too.

Perhaps the greatest failing of this superfluous book is that Clarke makes no serious attempt to explain the lofty claims in his subtitle. The only hint he gives about JFK’s “transformation” occurs in passing: a comment indicating that after the death of his infant son Patrick in August, he grew closer to his wife and no longer sought out new prospects for quickies when Jackie was away. But, of course, one can’t know if a surviving Kennedy would have resumed the sexual habits of a lifetime. Neither does Clarke define what makes for presidential “greatness”—among the more contested concepts in American political history. He suggests Kennedy was “emerging” toward it during his final hundred days when, after years of delay, he finally sent a sweeping civil rights bill to Congress. Yet it’s hardly clear he would have been able to defeat the opposing coalition of Southern Democrats and conservative Republicans—as did LBJ, with help from the memory of his martyred predecessor.

This failure to deliver on the promise of his subtitle is all the more irksome because, in that debatable idea of “greatness,” there is something to explore: In contrast to nearly every aspect of Kennedy’s life, the enduring grip of his memory does need to be understood more fully. Like most Americans above the age of fifty-something, I can recall, quite precisely, what I was doing and thinking when I heard the news from Dallas that Friday afternoon and for the rest of that weekend as well. But he died with his most significant policies—on civil rights, anti-poverty, and the Cold War—unfinished at best. So why JFK continues to be ranked among the greatest presidents and probably the most beloved one remains somewhat elusive.

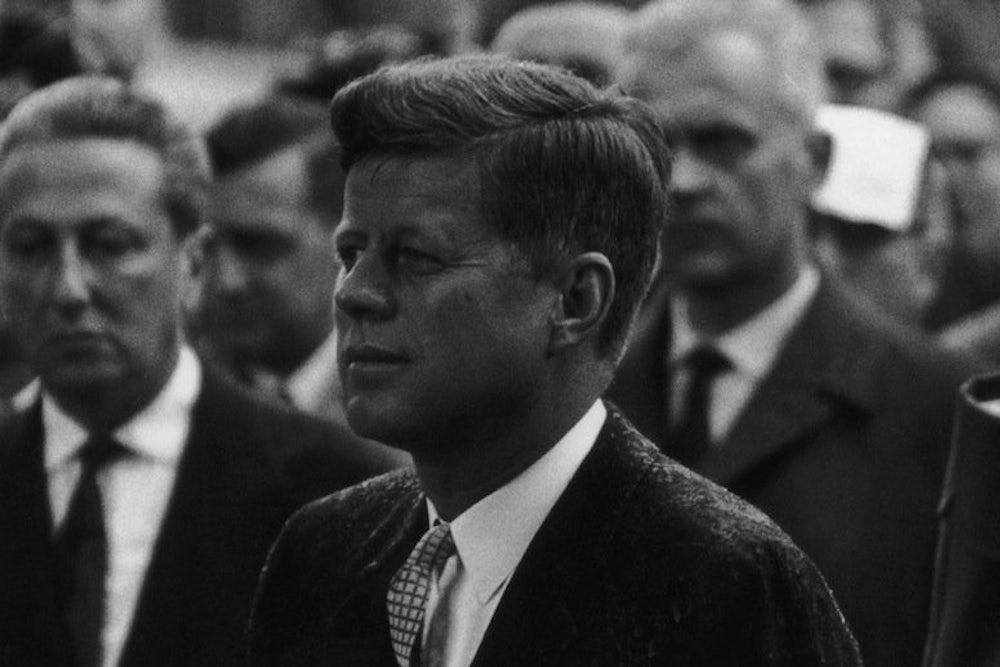

Surely his good looks, gorgeous wife and children, and a personality that mixed grace, wit, idealism, and toughness play a large part. Even larger is the incompleteness of his presidency itself. His death was a tragedy for his family, his country, and for his commitment to liberal reforms like civil rights and Medicare that even most conservatives now favor. Perhaps we still care so much about JFK because we yearn for a good, vigorous, and sensuous ruler, one who can make the old dreams live again, if only in words and pictures. There he is, our JFK, peering back at us from book jackets, old videos, the pages of Vanity Fair, and websites: the upswept hair, the decisive gestures, the buoyant grin. He will always be glancing toward a future that never arrives.

Michael Kazin’s most recent book is American Dreamers: How the Left Changed a Nation. He is editor of Dissent and teaches history at Georgetown University.