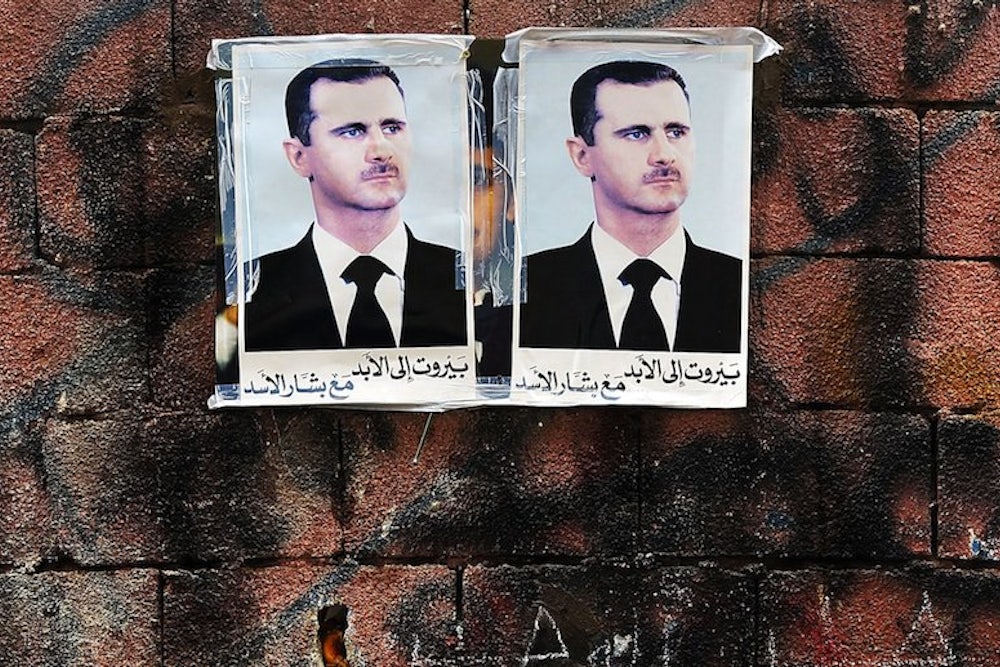

What was supposed to be the Syrian phase of the so-called "Arab Spring" has evolved into one of the greatest tragedies of the twenty-first century. The once-peaceful opposition to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's deeply entrenched and powerful Ba'ath Party regime has escalated into armed resistance and, finally, a brutal civil war—one that has now claimed close to 100,000 lives. This escalation poses a serious threat, not just to Syria's neighbors, but—given the existence of chemical weapons in Syria—to the international community as well.

The United States, like other nations supportive of the Syrian opposition, has chosen to act, but to do so primarily through diplomatic and economic means. Its hesitancy to take more direct action is understandable given the fractious nature of the opposition, but the cost of failing to influence the balance of power between the opposition and the Syrian regime could be high. I say this not only because of the horrific humanitarian toll that is being exacted, but also because the conflict is almost certain to spread to all of Syria's neighbors. Meanwhile, Assad, confident of his military strength and with support from Iran and Hezbollah, continues to wage war on his own people in what has now become an overtly sectarian conflict.

At this stage, it might appear almost too late for the United States to have an influence on the Syrian crisis. To be sure, providing small amounts of lethal assistance will not have much impact on the situation. Iran and Hezbollah are determined to keep Assad in power, even to the point of using their own forces. As such, the U.S. will need to do more to make sure that the provision of lethal assistance can affect the balance of power. This will require actually assuming responsibility for managing the whole assistance effort to the opposition.

This will not be easy. It will require coordinating all the disparate sources of support on the outside—from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Britain, and France—and ensuring that all money, training, weapons, and non-lethal and humanitarian assistance are channeled in a complementary and cooperative fashion.

There should be no illusions: Should the U.S. take over the management of the assistance effort—something that will require a serious investment of time and political capital on the part of the administration—transforming the situation and the balance of power will take time, and is not a given at this point.

After all, the Syrian opposition remains fragmented despite the formation of a Syrian National Coalition last year. Moreover, the Jihadist elements, having received the most money and arms, retain the upper hand within the opposition, at least at this juncture. To help influence a positive outcome, then, the U.S. administration would need to ensure that all assistance is going only to those who are committed to a non-sectarian, inclusive Syria. These groups are at a disadvantage now, and, even if they are given the kind of assistance and training that they need, it will take time before they are able to exploit it.

The larger point here is that the U.S., and others that support the opposition, need to have a clear objective. Providing more material assistance, including weapons, in a more systematic and coordinated fashion is a means to altering the balance of power on the ground, and that is the only way a politically negotiated transition can become possible.

That is the hope, and it remains a long shot at the moment. Not only must the opposition become more credible and less divided, but the international coalition that supports the opposition must itself become more unified and provide determined and consistent support to those fighting the Assad regime. Even if some sort of political agreement became possible, it would need to be enforced by an international peacekeeping presence.

If a political resolution to the situation seems like an increasingly forlorn objective, how can the United States respond to the ever more probable outcome that Syria will simply fall apart? Assad, whatever he believes, is not going to succeed. He may continue to control certain areas within Syria for a while, but a fragmentation of the country is more likely. Such a deterioration would pose a threat to the international community as a whole: Not only might al-Qaeda embed itself in what would effectively be a failed state, but the loss of control over Syria's chemical weapons could have catastrophic implications for everyone. If the situation does worsen along these lines, Syria as we have known it for decades will cease to exist.

At a minimum, assuming that a political solution proves impossible, we need to have a fallback strategy of containment that aims to build a buffer zone in and around Syria. While this is not a very satisfactory approach, the fragmentation of Syria cannot be allowed to destabilize the whole region.

Dennis Ross is counselor at The Washington Institute.