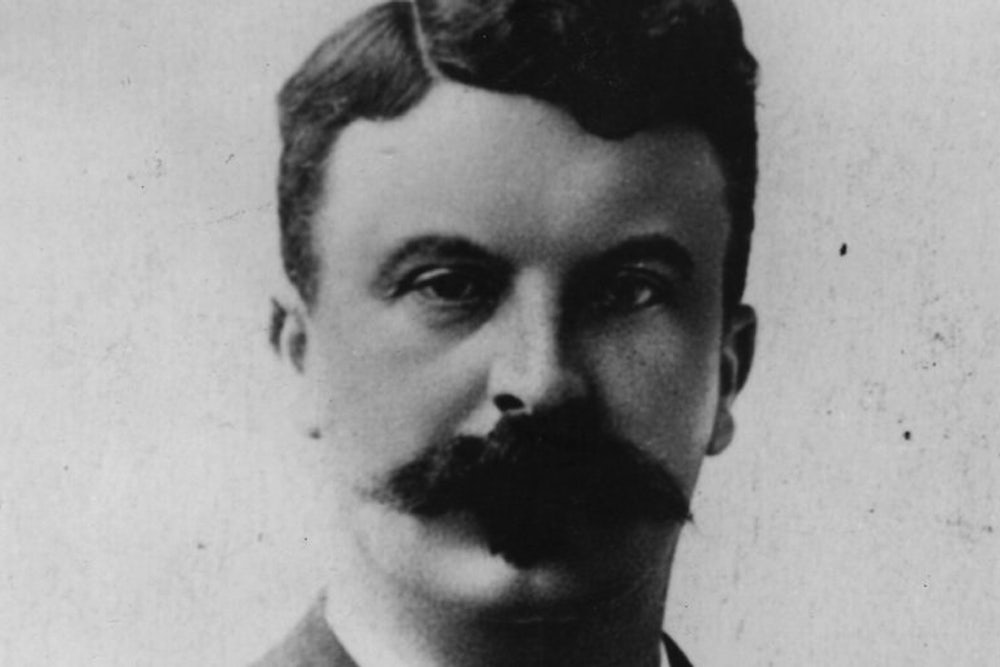

On the anniversary of Guy de Maupassant's birth in 1850, The New Republic's 1926 review of two books chronicling his life: Guy de Maupassant, A Biographical Study, by Ernest Boyd, and The Life, Work and Evil Fate of Guy de Maupassant, by Richard Harborough Sherard.

Only a few of Maupassant’s stories would be necessary to convince one that here was an extraordinary man, a gifted but singularly narrow and lonely sport of nature, powerful, relentless, capable, but incurably off the main track of humanity. At first, as one reads, one is struck by the lucid directness of the stories, by their cutting edge, their malicious veracity, their hammer and anvil solidity, their temperature, which like naked metal to the tongue in winter, is so cold that it seems hot. But soon, as one bloody or adulterous pattern gives way to the next, and the heavy preoccupations repeat themselves with insatiable chilled fury, one becomes both bored and horrified. Later, a curiosity is born of this repetition, this cruel obsession, and one reads on in order to find out what kind of a man the author was, and what was wrong with him. Not from the common itch to know what is wrong with anyone, and revel in eavesdropping knowledge, but because Maupassant fascinates, as well as repels, by his lack of humanity, his likeness to some mythical satyr and demigod let loose, to his sorrow and their bewilderment among human beings. Desires, animality, physical pride, amorous insatiability, he was endowed with to maniacal excess, but common friendliness, the sympathy that links one human to another, were left out of his make-up altogether. So much at least one learns by reading his stories and novels. It is by no means all: he was a much more complicated and pitiable, indeed a more likable fellow than his stories hint at. A full answer to the question, what sort was he after all, is given in these two books by Mr. Boyd and Mr. Sherard.

Of the two, Mr. Boyd’s is by far the better book. Both cover somewhat the same ground, but Mr. Sherard doubles back on his tracks, indulges in obscure circumlocutions, smacks his lips over his own luscious euphemisms, and manages to throw a self-conscious fog over what, when we come to Mr. Boyd’s version of the same events, seems perfectly clear. If Mr. Boyd’s volume were not here to challenge comparison, what Mr. Sherard has done could at least be put down as interesting, but in the face of Mr. Boyd’s capable directness, it is not even that. Mr. Sherard, who seems to have no very definite point of view of his own, cannot keep himself in the background. Mr. Boyd, on the contrary, is the admirably self-effacing guide, whose opinion as to the matter in hand we deduce from what he presents to us. Indeed, one wishes that he had spoken louder and longer in his own person, for the too brief judgment of Maupassant’s work in his last chapter is so good as to make one wish for a great deal more.

Mr. Sherard is the kind of person who can refer to Léon Daudet as a “thoroughly kind-hearted man.”

Maupassant’s life seems to follow now known pattern, and is full of dark contradictions. What manner of child he was might throw light on later darkness, but neither of our investigators has been able to find anything of really tell-tale value. How did it happen that this fearless, healthy, independent young fellow’s first step should have been so pettily cautious? It does not seem in the least like Maupassant to have pulled all sorts of wires in order to secure the smallest kind of a government post at an insignificant salary; it seems even less like him to have stayed there seven or eight years, filing dusty papers, playing the part, to outward view, of some anaemic, timorous little clerk waiting out the decades until his pension. After hours his impatient, ravenous vitality spent itself in boating, in love affairs, and, little by little, in learning how to write, in which he showed a slow, colossal, mental patience in strange contrast with the habits of his body. How did he keep these compartments of himself separate? How could he, the “taureau triste,” bend his nose so long to the grindstone turned by Flaubert? Perhaps, along with his physical furies, there burned inside him a slower indomitable fury to succeed, to be somebody, to write, perhaps it was an obsession only second to his chief obsession—women.

After this slow apprenticeship, success came to him almost overnight. With the publication of Boule de Suif in a collection of stories by followers of Zola, Maupassant was a made man. From then on his star flared to its climax for a few glorious years. But while still in his thirties, the curtain of madness and disease began slowly to descend. He wrote less and less, went further back into the past to find stories for his collected volumes, began to behave with paranoiac irritation toward his publisher, his friends, tried to commit suicide, was put in a strait-jacket, in an asylum, and at last flickered out, “like a lamp without oil.” Both biographers, Mr. Sherard a little more explicitly, lay the blame for his decay upon syphilis. Undoubtedly it finished him off before his time, but he had in him the seeds of mental and emotional disorders which would have warped his work had he lived. He was a victim of the most phenomenal satyriasis—to use Mr. Boyd’s term: he was never in love, but he had love affairs at all times and all places, with no matter whom, apparently, provided she was a woman. A woman always, never a human being to him, a fellow upon this world, worthy of affection, equality, understanding as well as conquest. He was as insatiable as he was omnivorous, as great a madness as the special form of disorder which finally dragged him down. Emotionally, he seems always to have been a cripple, though a cripple of gigantic, fabulous disproportion. This defect blasted and shriveled much of what his vigorous clear mind produced. For with this malady of the lower centres, the higher inevitably suffered also, and we find him spiritually, as well as emotionally, beggared and twisted. Supposing him to have been more normally inclined toward sympathy, kindness, understanding, what great stories he might have written! He had so much at his command: a superb narrative sense, a mastery of detail, a pitiless clarity of vision, a gift for motion, architecture, surprise, drama; what extraordinary stories these talents would have written if only allied with a little of the commonest sugar of humanity. And yet one is also forced to admit that to have taken away from him his obsession, his cynical, thirsty cruelties, would have surely robbed what he wrote of its terrible directness. Hard, if not always accurate hitting, was the most genuine of his abilities, and to ask that he be mollified by kindness is to try to take this ability away.

The long apprenticeship under Flaubert had its effect, but the effect, as Mr. Boyd points out, soon wore off, and in 1883, which Une Vie, ceased altogether. “That fatal facility and triviality of epithet and phrase which Flaubert tried to check, as in his comment on Désirs, made itself felt immediately after the stories in La Maison Tellier,” and Maupassant quite forgot his master’s excellent advice that the secret of originality lay in “looking at anything one wishes to describe long enough and attentively enough to discover an aspect of it which has never been seen or described by anyone else.” Even with these and other penetrating discounts, Mr. Boyd ranks Maupassant higher than would I. Granted that at his best, few other practitioners of the mechanics of narrative, scene setting, unwinding and final kick can touch him, granted that he builds up many unforgettable pictures, granted that he is a master of grisly and horrible effects, granted that he is technically supreme in the knack of pouring upon his reader, at the right moment, a thousand tons of ice-water in one single shock, he seems to me on the whole distinctly of the second rank. His characters, while often amazingly life-like, are very seldom alive; he sees them with irony, admiration, detachment, cynical placidity, but hardly ever with that sympathy which alone can cause to move marble, however accurately chiseled; he is that familiar type among novelists, the despot, who rules his characters with an iron hand, bidding them say this, do that, be there, an Olympianism that at best results in admirable puppets; he will not let well enough alone, either in one story, or in the series of them, but is forever rubbing in his cruder effects until we are bored and disbelieving; he lacks that essential faith and respect for human nature which can give breath, wings even, to silly and contemptible men and women; he does not respect or love life itself, he is apart from it, an unhappy, gifted, limited stranger, doomed to visit, upon his translation of it, his own excrescences and his own pitiful obsession.