Whether it is Jimmy Carter watching more than four hundred movies in the White House cinema or Barack Obama telling people that the flamboyant killer Omar on HBO’s “The Wire” is his favorite character, presidents have long engaged with pop culture. The content of that pop culture, however, has changed dramatically over the years—as has what it reveals. Here, in a the first of a series of short installments from What Jefferson Read, Ike Watched, and Obama Tweeted: 200 Years of Popular Culture in the White House, we look at some of the presidents’ favorite ways to pass the time.

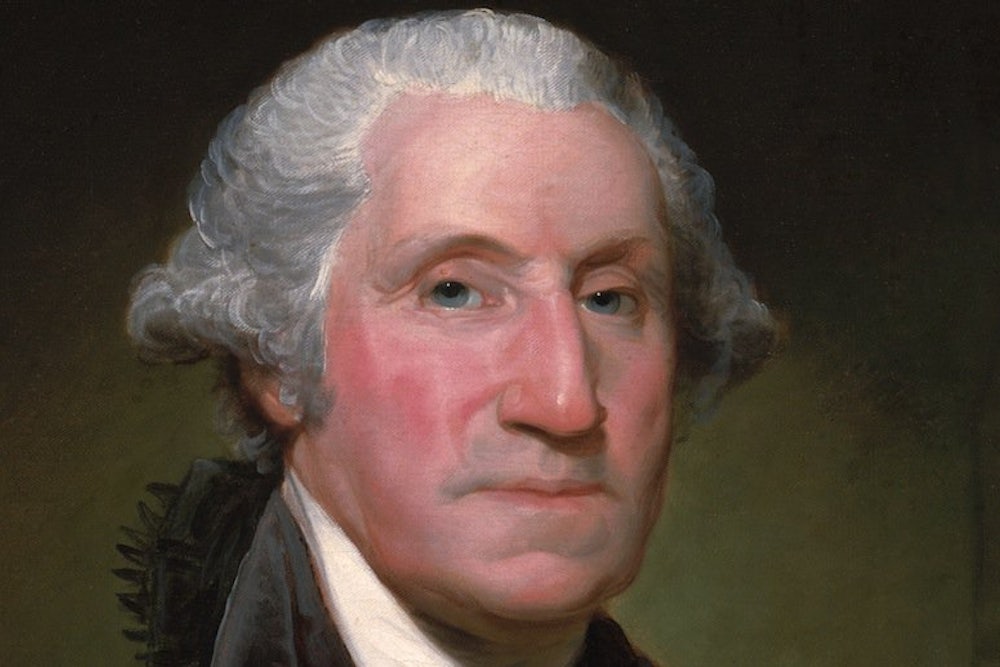

Though perhaps not thought of as a reader, George Washington had a nine-hundred-book library, considered quite large at the time. The library included biographies, histories, and classics from ancient Greece and Rome, as well as fiction. There is plenty of evidence, moreover, that Washington’s books were put to good use. Ever the autodidact, he had a penchant for practical books on agriculture and for military works.

Washington also borrowed books, though in at least one case the cares of high office seem to have distracted him from his duty to the volumes’ owner. The ledger of the New York Society Library indicates that on October 5, 1789, two books—The Law of Nations by Emmerich de Vattel and a volume of debates from the House of Commons—were checked out to the president. In 2010, an archivist discovered that the books had never been returned; the fine, adjusted for inflation, amounted to $300,000. Mount Vernon could not find the missing volumes in its collection, but it managed to acquire another copy of The Law of Nations, which it handed over to the library. In gratitude, the library canceled Washington’s outstanding fine.

Washington and his contemporaries not only read books, they discussed them as well. These discussions sharpened, clarified, and spread the Revolution’s ideas. Virginia’s George Mason was a key figure in these conversations. A prodigious reader, he owned an impressive library and had written manifestoes on representative government. Mason enjoyed talking about books and ideas with his fellow Virginians Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Washington, both over meals and in letters.

These conversations—more formal and substantive than gossip or banter—were a crucial method of developing policies on the weighty issues of the day. In 1790, for example, the famous “dinner table bargain” between Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison led to the establishment of the new capital at what is now Washington, D.C. The historian Catherine Allgor has stressed the importance of dinners to the entire founding generation, noting that the Revolution and the founding “unfolded” as part of a series of conversations, many if not most of them of the dinner-table variety.

During his presidency, Washington hosted what he called the Thursday dinners, with a mixed company sitting around a well-laid-out table. The dinners were formal to the point of awkwardness, with Martha serving as hostess. After a meal of many courses, the men retired to the drawing room to drink and discuss matters of consequence. These gatherings were similar in some ways to the famed Georgetown dinner parties of the not too-distant-past. In an age with fewer opportunities for communication, however, social events like the Thursday dinners served a purpose similar to that of today’s universities, think tanks, and other institutions dedicated to intellectual discourse.

Excerpted from What Jefferson Read, Ike Watched, and Obama Tweeted: 200 Years of Popular Culture in the White House. Tevi Troy is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.