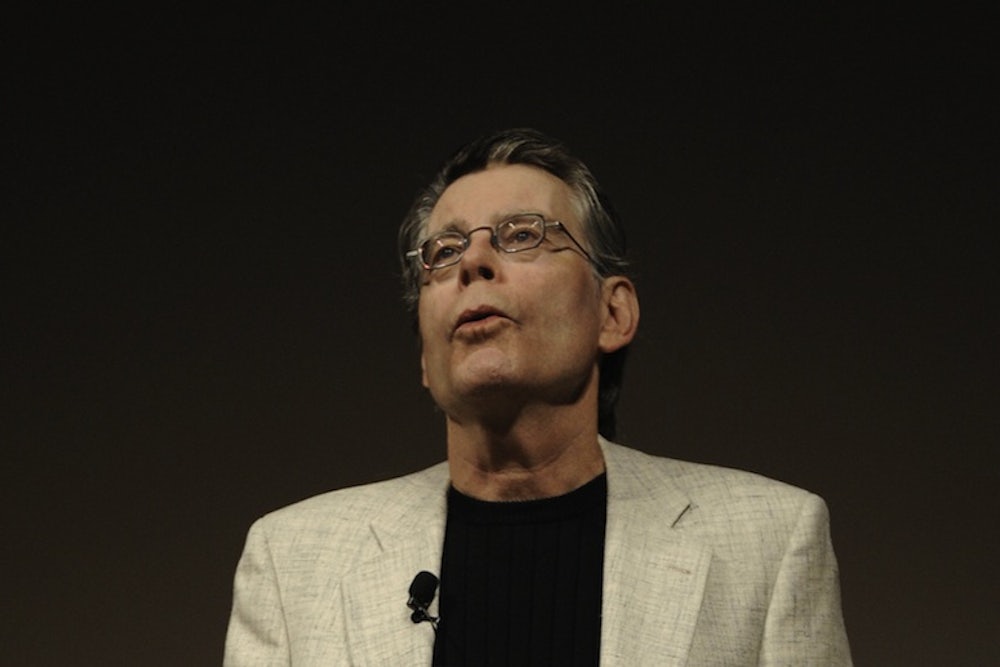

I am a Stephen King fan. This weakness has caused me a good bit of embarrassment—especially during my former life as a graduate student, when I was expected to spend my days reading large, solemn books. I have been known, in fact, to conceal a King paperback inside a more weighty-looking tome. And when I buy King's latest offering, I usually do so at a secondhand bookstore, so that when I'm finished, I can guiltlessly throw it away or leave it on the subway—thus diminishing the likelihood that anyone will ever discover the offending volume on my bookshelves.

But now it appears I no longer need be embarrassed by this predilection for pulp. A movement is under way to rehabilitate (or perhaps simply habilitate) Stephen King as a Serious Writer. It began several years ago, when King left Viking, his longtime publisher, and moved to Scribner. It was rumored at the time, according to The New York Times, that King "felt frustrated at being pigeonholed as a horror writer and wanted to be taken seriously as a `real' novelist." The New Yorker took the bait shortly thereafter, publishing a lengthy profile that included earnest examinations of a number of King's books, including Bag of Bones, his first novel for Scribner, whose book jacket displayed approving blurbs from Gloria Naylor and Amy Tan. The latter said Bag of Bones "places both the ghost story and Stephen King in their proper place on the shelf of literary American fiction."

To be sure, praise for the novel—a heavy-handed commingling of subplots vaguely derivative of Rebecca, Beloved, and The Dark Half—was less than universal. ("What ... are we to make of a supernatural saga in which the ghosts are less terrifying than the [literary] agents?" wondered The Times' Daniel Mendelsohn.) Still, King's subsequent projects have been accorded somewhat more gravitas than his earlier efforts. Last year's The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon was lauded as a touching psychological thriller happily devoid (well, nearly devoid) of ghouls or gore. With the novella Riding the Bullet, King became the first author of his stature to publish a work exclusively online. And this month King capped his recent run with a book of an entirely different sort—On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. The book was the focus of a sympathetic profile of King in The New York Times Magazine, which cited Cynthia Ozick on King's belletristic qualities: "This man is a genuine, true-born writer.... He writes sentences, and he has a literary focus, and his writing is filled with literary history."

It's hard to deny that King writes sentences. And he does have an uncanny knack for seizing on the descriptive detail that makes you willing to suspend disbelief for even the most preposterous conceits. But that's a far cry from having a "literary focus"—as On Writing makes all too clear. Equal parts memoir, style handbook (including such gems as "The road to hell is paved with adverbs"), and advice manual for beginning writers, the new book offered King an ideal opportunity to argue the case for his inclusion in the literary canon. Instead, it provides persuasive, if circuitous, proof of exactly the opposite.

While many writers are competent and some are "really good," King argues in On Writing, only an idiosyncratic few are actually great—"the Shakespeares, the Faulkners, the Yeatses, Shaws, and Eudora Weltys." He continues, "While it is impossible to make a competent writer out of a bad writer, and while it is equally impossible to make a great writer out of a good one, it is possible ... to make a good writer out of a merely competent one." King finds this idea democratic, inveighing against literary critics and writing teachers who believe that "writing ability is fixed and immutable; once a hack, always a hack. Even if a writer rises in the estimation of an influential critic or two, he/she always carries his/her early reputation along, like a respectable married woman who was a wild child as a teenager." It's hard not to guess to whom King might be referring.

Having posited that it's possible for merely competent writers to become good, King proceeds to his definition of "good fiction." Story, he says, should be the primary concern—writers needn't worry too much about language or characterization. "Book-buyers aren't attracted, by and large, by the literary merits of a novel," he writes. "Book-buyers want a good story to take with them on the airplane, something that will first fascinate them, then pull them in and keep them turning the pages." King then goes further: Story is not only what readers want; it's also the part of the book that is "the truth." "When I ... face another review that accuses me of being a vulgar lowbrow—which to some extent I am—I take comfort from the words of turn-of-the-century social realist Frank Norris," King writes. "Norris's books provoked a good deal of public outrage, to which Norris responded coolly and disdainfully: `What do I care for their opinions? I never truckled. I told them the truth.'"

It's true that what makes King's books so frightening is that in their best moments they lay bare very real human fears—primarily that we, or those we love, will die. But being true is not the same as being great, or even good. Take Pet Sematary, King's 1983 novel about a man who inters the family cat—and then closer relatives—in an Indian burial ground that brings them back to life, sort of. The root of the book's scariness is the disturbing truth that if a person you love dies, you will do anything to get him or her back, in any form. And King is a good storyteller—he keeps the action fast and sharp, the dialogue short and uncomplicated, and the sentences (mostly) unfettered by adverbs. But he can't resist taking full advantage of all the easy, creepy details one associates with the living dead—bugs crawling out of eyeballs, the stench of decomposing flesh, and so on. In fact, King hides his emotional truths under so much simplistic prose and horrific detail that even those of us who believe they are there sometimes have a hard time finding them. Characters drink beer and sleep with their wives and love their children, but their inner lives generally don't get in the way. The fast pace keeps fans like me turning the pages, but the story doesn't contain anything essential that lives on in our minds after we've put the book down.

There are other ways to tell a good story, even a good ghost story. The undead make more than a cameo appearance in Dante's Inferno, but they're not just showcases for gruesome description or devices for furthering the plot. There are (debatably) ghosts in The Turn of the Screw, too, but that book is no more about spooks than Crime and Punishment is about homicide. Those stories, it need hardly be said, are literature. Stephen King's, by contrast, will pass the time nicely on an airplane.