Americans today vacillate over national security and government power. We want an effective intelligence community, but we don’t want too much surveillance or collection. We want to rein in the NSA, but we also wax outraged when it does not connect the dots. We want to capture the enemy, but we want to close Guantanamo Bay. We want to kill the enemy, but drone strikes make us uncomfortable. The further we get from the September 11, 2001 attacks, the less tolerant we are of strong government actions to prevent future attacks—except when something like the Boston marathon bombing happens, when we immediately want to know why the government did not do more and know more.

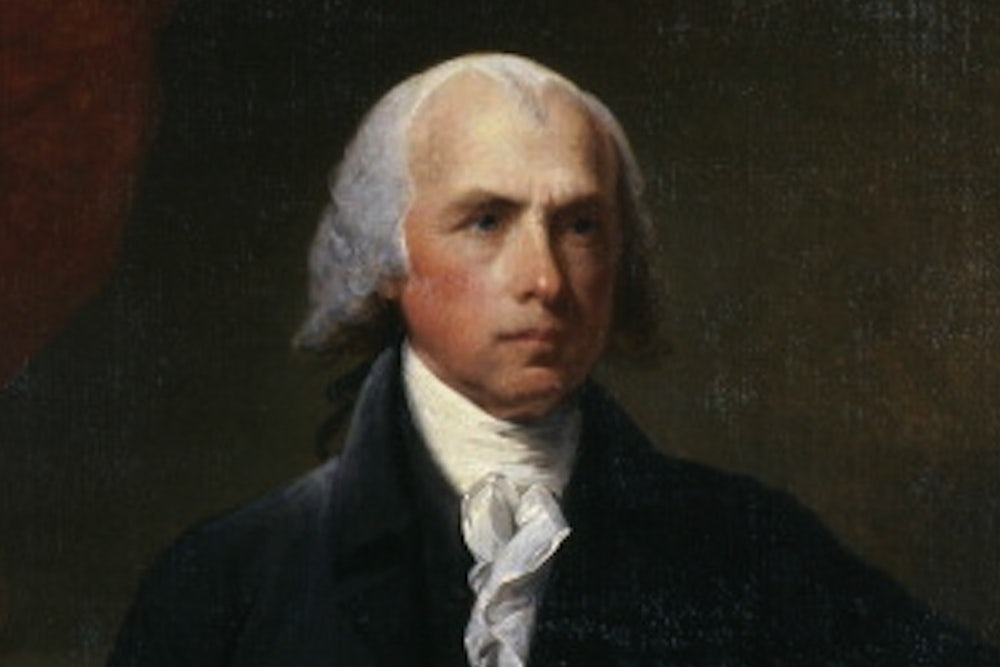

Our vacillations are honorable, and they are also very old. The Father of the Constitution, James Madison, himself went back and forth over the course of his long career—as Founder, as opposition leader, and then as President—about how security should inflect the powers we invest in government. In Madison’s vacillations, we see fascinating prototypes of our own.

As part of the Virginia delegation to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, James Madison was one of the most vocal supporters of a strong Union. Both behind the scenes in the years leading up to the Convention, as well as during the bitter debates of the Continental Congress, Madison maintained that a robust federal government and a successful Union were inextricably linked. One of the key motivations animating his desire to strengthen the government was his concern about security. He was wary of humiliation by foreign powers, and worried that absent stronger central leadership, the states would continue warring with one another—as they were apt to do over issues of commerce—leaving countries like Spain, France, and England to exploit the divisions between them. Madison believed that if America was to comport herself effectively abroad, she would have to speak with one, unified voice. She would also have to defend herself if she were invaded by foreign powers. During the Virginia Ratifying Convention on June 16, 1788, Madison elaborated: “[W]here is the provision for general defence? If ever America should be attacked, the states would fall successively. Where is this power to be deposited, then, unless in the general government, if it be dangerous to the public safety to give it exclusively to the states?”

The young country also faced no shortage of domestic security concerns. During the federal convention, Madison made the case that the country had to be able to suppress insurrections and preserve internal stability. He pointed to violence in Massachusetts at the time and the existence of slavery as evidence that a minority could overpower the majority if it so desired. All of this, in his judgment, necessitated greater federal power.

But over the course of the 1790s, Madison’s attitudes changed. Under President Washington, Alexander Hamilton was appointed Secretary of the Treasury. Madison’s relationship with Hamilton—previously cordial and cooperative because of both men’s aspirations for the Union—had begun to fray. And Hamilton’s ambitious plans for the country’s finances brought Madison great unease. Madison considered many of these measures blatantly unconstitutional and a vast overreach of federal authority. His discomfort was further heightened by the Hamiltonian plan to create a national bank, and his convictions about the necessity of a strong central authority began to wane—notwithstanding security concerns.

This was a period in which the young country was navigating its way between France and Great Britain, themselves in perpetual rivalry. President Washington had signed the Proclamation of Neutrality, declaring America impartial in the conflict between the two great powers. He sent John Jay to London to negotiate a treaty governing the terms of American commerce with Great Britain in 1794. Hamilton wanted to preserve England’s maritime hegemony because the young American economy depended so heavily upon it. Madison, by contrast, took the view that France would serve as a counterweight to British arrogance and allow the United States to prosper.

According to Madison’s biographer Ralph Ketcham, even as news of British misbehavior began coming in—of impressment of American ships and her fomenting of unrest among Indians in the West—Madison did not support the augmenting of the army and navy sought by Hamilton and the Federalists. As a matter of principle, he refused to cede any more power to the executive to prepare for war. Almost two decades later, as president, he would come to reverse this view.

Madison held the same line during the Whisky Rebellion in the summer of 1794. Despite the real and troublesome domestic unrest that was taking place in western Pennsylvania, Madison did not support governmental force as an answer; he believed it would set an unhealthy precedent of federal high-handedness in enforcing the law.

When John Adams became president 1797, Madison had taken a step back from political life. President Adams urged domestic military preparedness to thwart the prideful advances of France; Madison, removed from the capital, and familiar with this sabre rattling, continued to move further away from his nationalist beliefs about a strong executive at the helm of the country. He only re-entered national politics because he found the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 so appalling. These were security measures, passed in anticipation of potential conflict with France; the latter of these two laws criminalized criticism of the federal government and its policies, making it a crime to “write, print, utter or publish . . . any false, scandalous, and malicious writing against the government of the United States, or either House of Congress, or the President, with intent to defame, or bring either into contempt or disrepute.” Madison quickly became one of the primary opponents of the Acts, and as a member of the Virginia Assembly, he authored the famous Virginia Resolutions in 1798 and the Report on the Resolutions of 1800—both of which assailed the Acts on constitutional grounds.

And when Thomas Jefferson was inaugurated as president in 1801 and Madison became his most trusted advisor and counselor as Secretary of State, the pair truly attempted to govern the country under the cherished Republican ideals of a limited federal footprint and a restrained executive.

In this period, domestic insurrection continued to challenge Madison’s long-held views of executive power. Federalists in New England had become much better organized, and they regularly threatened secession and conspired with foreign officials. Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s first-term vice president, was prosecuted for treason for attempting to ferment unrest in the West and South, overthrow Jefferson’s administration, and form an independent nation. There were even rumblings of discontent from members of Madison’s own party. Yet the Jefferson administration reduced the size of the armed forces and scaled back the judiciary.

On the other hand, the need to govern challenged Madison’s commitment to limited federal involvement. The Louisiana Purchase was certainly not the work of an executive adhering strictly to those powers enumerated in the Constitution. And the Jefferson administration kept Hamilton’s detested national bank in place.

Madison’s ideals were most sorely tested during his own presidency, when he actually had to fight a war with a naval superpower using a presidency and a federal government he had worked hard to weaken. This was made especially difficult by the fact that when he finally asked Congress to declare war, he was faced with focused, concerted, and energetic opposition from the New England Federalists, who threatened secession, marshaled state resources to oppose federal policy, and even openly sided with the enemy. Yet Madison never flexed his executive muscles in the same way as other wartime presidents have. He tolerated risks and took painful care to restrain his own actions, even though precedents like the Alien and Sedition Acts had been enacted for national crises far less severe. Madison’s adherence to the proper role, as he conceived it, of the republican executive, arguably held him back from greater success in the War of 1812, which ended in a stalemate.

Yet at the end of the day, having enhanced federal power, in part, for security reasons, and having opposed federal power despite security concerns, the one president who ever sought to fight a war without augmenting executive power ultimately took critically important steps to do just that. As Steve Budiansky, author of a naval history of the war, writes:

[T]he war’s outcome almost instantaneously forged a new consensus at home that embraced a standing army and navy as an essential expression of American national strength, prestige, and diplomatic influence in both the Western Hemisphere and Europe. Two decades earlier, Alexander Hamilton had promoted that characteristically Federalist view of military power. . . .That kind of thinking had been anathema to Republicans. But now all of the speeches about militarist “adventurism” and “tyranny” evaporated almost overnight and Republican opposition to the navy was hardly to be heard. In a passage that Alexander Hamilton himself might have written, Madison acknowledged in his message to Congress announcing the end of the war that a chief lesson of the conflict was that “a certain degree of preparation for war is not only indispensable to avert disasters in the onset but affords also the best security for the continuance of peace.”

In the wake of the war, Congress authorized an increase in the navy. It bolstered the army. Under James Monroe, Madison’s successor, West Point was revived. Republicans had rediscovered that federal muscularity on security issues was essential to a successful union.

Our point here is not that Madison was a hypocrite. He wasn’t. And neither are we moderns. All of the values and powers Madison spoke for at different times in his career were sincere, and reflect the essential ingredients in the complex stew that is a society committed to self-government, liberty, and secure continuity over time. Similarly, in our era, we vacillate between authorities and restraints that each reflect big parts of who we are—none of which we can really allow to prevail over the others. And in invoking each of these powers and restraints, we hear echoes of Madison, which is why people on all sides of these debates tend to quote him.

Madison said and did a lot of things—not all of them consistent with one another. But in his movement between them all, we see ourselves.