This piece originally appeared on newstatesman.com.

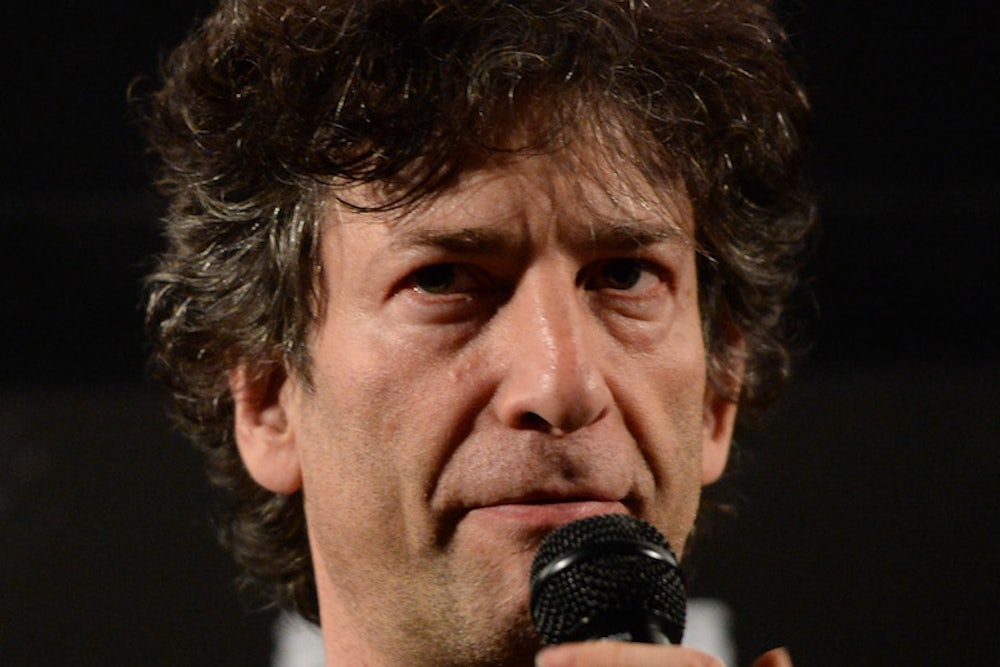

Neil Gaiman has been wearing the same outfit since 1987. Occasionally the black T-shirt gets changed or one billowy black coat gets replaced with another billowy black coat but the basic look has stayed the same. With his messy dark hair and air of permanent distraction, Gaiman had a personal brand long before people used the phrase. It’s almost enough to overwhelm the man himself. Almost.

We meet at the Covent Garden Hotel, where Gaiman is staying on the London leg of his latest book tour, and head out to find food. On the way, we pass by Forbidden Planet, the enormous warehouse of comics and geek paraphernalia on Shaftesbury Avenue. I’ve got an idea, I say. Instead of me asking you questions, why don’t we just go in and you can stand in one of the aisles full of graphic novels, being Neil Gaiman. Just stand there. Just stand there and see what happens. I’ll hide around the corner and watch. It’ll be great, I say.

“I hate you,” says Neil Gaiman.

The interview is going well so far.

Gaiman is perhaps the world’s best-known fantasy writer. The internationally bestselling author of Neverwhere, Coraline, American Gods, Stardust and many other books, graphic novels and film adaptations is rich, famous and married to a rock star. He has millions of devoted fans who eat his every word like air. He has won every major award going for science fiction, fantasy, and children’s literature, including the Hugo, the Nebula, the Bram Stoker and the Locus, many times over. He spends most of his time flying around the world between homes and fancy hotels, being celebrated and signing an improbable number of books. He is almost always tired and almost always jetlagged, and if we were to pull the Forbidden Planet prank, he might well be torn apart by anguished nerds in the manner of ancient Greek revelers in a Bacchanalian frenzy. And wherever he is in the world, whatever time it is, somebody can probably be prevailed upon to bring him a pen and paper and a cup of tea.

So, is this as good as it gets for a writer?

“No,” says Gaiman. “This has huge problems, which are mostly about writing. I’m currently dealing with how to go back to being a writer. Rather than whatever it is that I am. A traveller, a signer, a promoter, a talker, a lecturer. I’m building new ways to get back to being a writer, because there are lots of things that are more fun than sitting in a room, on your own, writing stuff, that have to do with actually interacting with other human beings. And going out and doing stuff.” It’s no coincidence, he tells me, that The Ocean at the End of the Lane was written when his wife, Amanda Palmer, was away making an album.

“Is it as good as it gets in terms of what you might call fringe benefits?” he adds. “Yeah, I guess it probably is. It’s interesting being rich, for example. But in any real terms, from my perspective, I’m dull. I don’t have any expensive hobbies, I don’t have any expensive tastes. I felt rich at the point where I could always afford to eat out at a restaurant and never worry about what the bill was. And that was 20 years ago.” These days, Gaiman has a charitable foundation, set up to give away the extra proceeds of his work “sanely.”

He has come a long way from East Grinstead. Gaiman grew up in the town in West Sussex, the eldest of three children, and spent most of his time at Church of England schools lost in fantasy and horror novels—he cites Michael Moorcock, Roger Zelazny, Ursula K Le Guin, C S Lewis, and H P Lovecraft among his early influences. He was already married to Mary McGrath and had fathered the first of his three children when he began sharpening his teeth as a journalist in the mid-1980s, but hackery was only ever practice for the stories, which were constructed from the start with a delicacy that belies the dense and heady imagination at play. Stephen King described Gaiman as “a treasure house of story,” adding that “we are lucky to have him in any medium.”

Gaiman published his first short story in 1984, but it was the Sandman graphic novels that put his work on the world stage. Now, more than 25 years after the first issues were published, a new Sandman comic has appeared. And on 21 November Gaiman is releasing an ebook to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who, for which he has written several award-winning episodes. It is possible that only someone who grew up as a fan of the show would have such an exquisite grasp of what keeps his own fans happy.

We head back for tea in the library at Gaiman’s hotel. It is a wood-paneled place with an open fire, which could be the set for the sort of children’s television show where the presenter reads stories aloud with the help of a friendly puppet. There is no puppet, but there is a succession of very polite waiters bringing impossibly delicious biscuits. You get the feeling Gaiman’s life is full of impossibly delicious biscuits.

With enough tea and biscuits inside him to counter the jetlag, Gaiman is charming and witty, and speaks in the slow, soft tones of someone who is used to telling stories for a living and people paying attention to them. When he is storytelling—and interview mode, for someone with his years of practice, is a kind of storytelling—Gaiman is magnetic. But not all the time. Often, in between anecdotes, the eyes glaze over, and he is looking at something in the middle distance, just at the edge of sight. His speech drifts almost into silence, and Neil Gaiman is ... somewhere else.

I want to say that I have never met anyone before who was quite so obviously away inside their own head, seeing the bodies around them as shadows, as source material. That’s not true. I have met others, but they have mostly been lonely adolescents, brilliant academics, psychiatric patients, or a combination of the three. That’s when you remember that, more than anything else, Gaiman’s work is about escapism and he appeals to those who long to leave their lives. Which, at some point or another, is almost everyone.

Gaiman’s most successful books follow a basic pattern. Beneath the everyday, below the skin of the humdrum, is a dark otherworld and ordinary people—lost, lonely people—can find their way there if they are very brave or very lucky. An ordinary office worker steps through a doorway into a world of steampunk gangsters and ancient legends hidden under London. An ex-con is taken on a road trip to a land where all the gods of America are real. A farmboy steps over a gate into fairyland to bring back a piece of a star for his sweetheart. A little girl whose parents neglect her finds her way into a mirror-home with mirror-parents whose eyes are buttons. A little boy escapes a massacre and is raised by ghosts in a graveyard.

Escape. Adventure. The magical door in the wall that lets you out of your life and into a new one. Gaiman has perfected that formula, and nobody does it better. No wonder his readers love him like a drug.

Other fantasy writers and graphic novelists who are considered Gaiman’s contemporaries—Warren Ellis, China Miéville, Alan Moore—have a political agenda, however covert. Apart from some engagement with the LGBT rights movement in its early years, Gaiman’s work is pure escapism, which is perhaps what made it so spectacularly popular in the 1990s and 2000s: a time when people were allowed to dream about having different lives but not about how to change their own. Those were years when young people needed stories to help them survive. We still do.

“People often ask me, ‘How do you feel about the fact that what you write is fundamentally escapist?’ And I say, ‘Well, the big thing for me is there’s nothing wrong with escape,’” Gaiman says. “Someone who is in a difficult or impossible situation who is offered an unlocked door to somewhere else that they can go through, and they can go through and they can get away, and they can genuinely get away. And not only can they get away, but while they’re away they can learn things, and gather armor and gather knowledge and gather weapons that they can take back into their prison and make it better. That’s a good thing. That’s not a bad thing.” He quotes J R R Tolkien’s aphorism: “the only people who inveigh against escape are jailers.”

Gaiman’s latest books, both published this year, are variations on that theme. The first, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, is an adult horror story about a lonely, bookish child growing up in Sussex who meets ancient monsters at the bottom of the neighbor’s garden; the most recent, Fortunately, the Milk..., is a children’s book about a father who makes up wild stories to explain to his children why he’s late coming back from the shops. The father, as illustrated by Chris Riddell, looks a lot like Neil Gaiman.

“My son Mike, I remember him once looking at me at the dinner table, as I’d finished some extended flight of fancy about something or other, and saying: ‘You’re making stuff up. Why do you keep making stuff up?’ And I said: ‘Because it bought your dinner!’” He laughs. “But it’s true. I’m incredibly lucky that I live in a world in which, since I was 21 or 22, everything that I have eaten, everywhere that I have lived, every penny, feeding my children, it’s all been done by me making stuff up and writing it down.”

It’s not the first time Gaiman’s work, despite being the very soul of whimsy, has been so self-reflexive. Fortunately, the Milk... has pirates, vampires and a time-travelling Stegosaurus in a hot-air balloon, but it is fundamentally about a father who makes up rather too many tall tales. Most readers of the early Sandman comics noted how much the main character – Morpheus, the King of Dreams – was drawn a little like a cartoon version of Gaiman, all pale and lean and messy-haired and angsty. Gaiman has been writing himself as the Dream King for many years since Sandman finished.

Gaiman is a master storyteller and the story he is paid to tell half the time right now is the story of being Neil Gaiman. This is not his fault. Quite a lot of writers imagine themselves as a global brand with armies of publicists and fans to appease, but few of them actually expect to get there. Gaiman is not the only one invested in the image of himself as a teller of tales. His publishers are also invested. But most of all, his fans are invested.

And what fans. Gaiman may very well be the best-loved author in the world. J K Rowling may have had more influence over a certain generation of young readers, but the Harry Potter author holds herself aloof, claiming to have tweeted only ten times in her life. Gaiman is always on Twitter, engaging with fans directly, blogging, and acting out his long-distance romance with Palmer—who has her own devoted legion of followers effusively in public.

“The thing is, mostly, no matter where you are, it’s the same; whether you’re in Moscow or the Philippines or Brazil or America, the fans are the same. They’re people who have read something you wrote and it touched them, or it changed their life, or it opened a door or a window and showed them a world they might not otherwise have seen, and it’s important to them.

“When I was a young writer, I’d get people saying, ‘Your character Death, in Sandman, got me through the death of my son/the death of my brother/the death of my husband/ the death of my grandfather.’ And I would think, that’s very nice, but I didn’t make it to do that. That it did, that was a byproduct, I can take no credit.

“Now I’ve been doing this long enough that we’re into a peculiar phase three. Running into beautiful, poised, adult young women, a little bit younger than you, who tell me that Coraline saved their lives, got them through late childhood. This was their book that they held on to. It taught them about bravery. Sometimes they would tell me about how it got them through times of abuse. And this stuff actually is big and important. To give people tools. Mind tools that they can use to deal with real problems.”

I remember reading Gaiman’s comics as a prepubescent, and it occurs to me again that for people who are practically powerless—miserable children, for example—an escape route is the best thing they could imagine.

Gaiman has been approached by the Guinness Book of Records to make an entry for most books signed. He turned it down, but he estimates that during the last tour he must have signed more than 75,000 copies of The Ocean at the End of the Lane, which, I point out, is more words than in the book itself. Gaiman tweeted a picture of himself after a marathon signing session painfully plunging his hand into a bucket of ice that somebody had brought him. It’s the sort of be-careful-what-you-wish-for story that he might have come up with himself.

Gaiman has a stock of anecdotes about his childhood and adolescence in East Grinstead, but he usually answers few direct questions about it and for good reason. His parents were important members of the Church of Scientology in Britain, although he himself is no longer a member. Snatches of interview material with a very young Gaiman explaining the workings of the church’s mythology can be found online but the adult author has a habit of shutting down interviews when the subject is raised, a habit I’ve been warned about.

I ask him anyway. I suggest that perhaps growing up in the church gave Gaiman a taste for fantasy, for the power of myth. He deflects deftly, politely telling me instead how he was fascinated by the stories he learned while spending time with his Jewish relatives in north London. He tells me that he spent most of his schooldays reading, which most of his readers can relate to, myself included.

“I’d get my parents to drop me off at the local library on their way to work. Sometimes I would pack sandwiches, normally I wouldn’t. And I would just read until it shut at six o’clock at night. Sandwiches were faintly embarrassing because I would have to go out and eat them in the car park because you couldn’t eat in the library, and I would have to leave. It was a long-closed-down little library on the London Road. And when I was at school, when things became intolerable and life was intolerable, I would go to the matron’s office and claim that I had a headache and then be sent into this little library. You’d get an hour and a half or two hours there.” Friends from Gaiman’s schooldays, including fellow members of the punk band he was in, confirm that he was consistently elsewhere, off reading—escaping.

“I was human in 1976, everybody was in a punk band,” Gaiman says with a little smile. “I was singing. It was originally called Chaos. With a ‘C’. We could spell. Also, it worked well with the logo.”

The band lasted a few months, until “the first time somebody threw a full can of beer at my face and I was taken off to hospital to have my chin sewn up. I remember one of the men with the gurney saying, ‘Look at this guy, they’ve completely beaten the shit out of him. Look at those eyes!’ and the other one going, ‘No, I think he’s wearing eye make-up.’”

I have to stop the flow of anecdotes to ask what comes next, which is another episode of Doctor Who, along with the tie-in ebook.

In the window of Forbidden Planet, a young fantasy novelist’s first book is for sale, next to a large picture of the author looking broody and otherworldly, with messy, dark hair, hunkered down inside a big black coat. I look at the portrait, and then at Neil Gaiman, and then back to the portrait.

“Look,” I say, “look what you’ve done.”

“I’m sorry,” Gaiman says, shrinking theatrically inside his big black coat, “it’s not my fault.”

Oh, but it is. Since at least the late 1990s, Gaiman’s career has been the aspirational model for most writers of the fantastic, as well as thousands more working in the creative industries with one eye on the weird. “He is smart, he makes things happen,” says the writer and critic Roz Kaveney, who has known Gaiman since he arrived on the London literary scene as an ingénue in mirror shades. “He ups the game of everyone around him,” she adds. “Reading Neil, you learn to love almost all characters. He is amoral enough to have a soft spot for really bad people, without minimizing that they’re bad. He loves their glee. He got laid a lot.”

The streets we are walking through are the same tucked-away alleys behind Tottenham Court Road that Gaiman haunted with Kaveney and other neo-gothic writers and graphic novelists more than half a lifetime ago. And yes, he is a little wistful for those more restless days, when he still had to prove himself.

“There is a weird danger zone you get into,” he says, “where [editors] have no power, because what they want is your name on their book, or whatever. So, you write a short story and you hand it in, and you’re not sure if it’s any good or not. And everybody goes, ‘Oh this is wonderful, thank you so much.’

“It was much, much more fun being absolutely unknown, and have people go, ‘Oh my God, this guy’s good’.” And for a flash, you can see that it’s still there, the hard hunger that makes the difference between an artist and a legend. Neil Gaiman has written himself into a legend that now has a life of its own. The question is what he’ll choose to do with it next.

Laurie Penny is a contributing editor to the New Statesman.