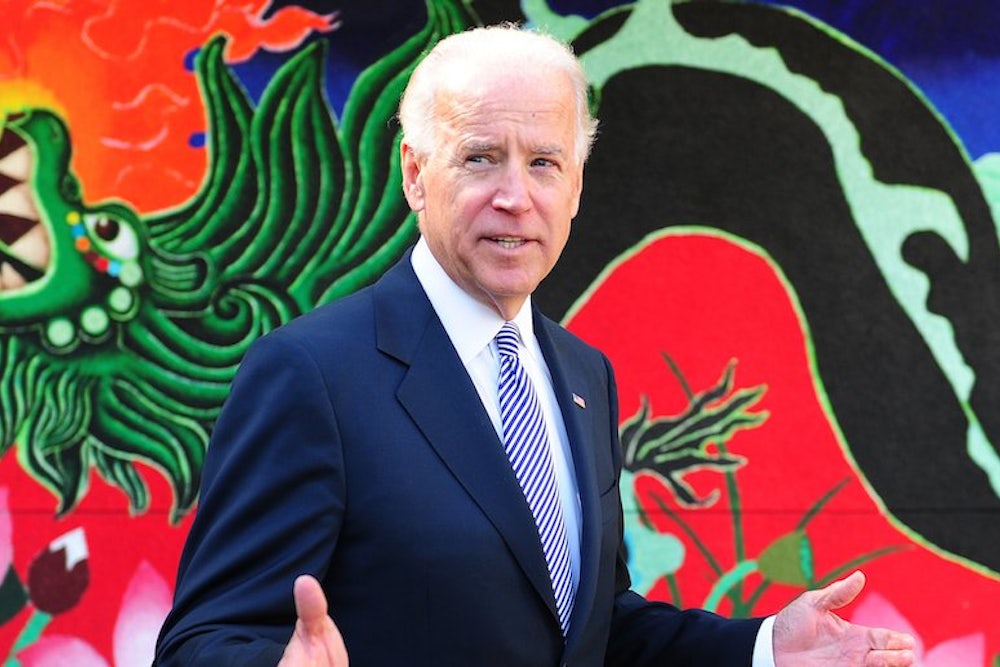

Vice President Joe Biden’s visit to Beijing this week has been an act of high-wire diplomacy. His tasks have included strengthening his personal relationship with President Xi Jinping, hashing out points of contention like intellectual property and protectionism, and diffusing tension over China’s newly-declared Air Defense Identification Zone. On the one hand, Biden is the perfect man for the job: Affable, relaxed, and, says one China expert, “someone that can cut through all of the ritual pomp and rigidity.” On the other hand, he’s also the person most likely to make a bad joke and start World War III.

His counterparts aren’t likely to slip up. Chinese politicians are notoriously on-script, rarely if ever speaking to the press in the kind of unmediated, free-wheeling way that regularly lands Biden in the soup. If they do fumble their words, they can always trust the state-run media to scrub the error. Rare moments of humanity get reported only if they’re harmless, like when President Xi Jinping greeted a resident of Wuhan by saying, “Hello, beautiful” (a perfectly normal greeting in Mandarin). During his ten-year presidency, Hu Jintao was on-record making one joke—and it was tame.

So China doesn’t have political gaffes in the classical, Biden-esque sense. But it does have its own, particularly Chinese versions of the political stumble.

One gaffe type is the bald-faced lie. The most notorious example must be that of Wang Yongping, the former spokesman for the Railway Ministry. When briefing reporters after the 2011 Wenzhou train crash that killed 40 people, Wang stuck to the government’s dubious initial story. “Whether you believe it or not,” he said, “I certainly do.” He was promptly fired. (And given another job.) Cousin to the straight-up lie is the flagrant neglect of reality. A high-ranking official, when asked by a reporter in 2009 if he supported government leaders disclosing their assets, came back with this: “Why don’t the common people disclose their property?”

More common is the “Kinsley gaffe,” i.e. speaking the truth accidentally. A traffic cop in Chengdu became Internet famous in 2010 for letting an official’s car through first and telling a nearby driver, “I only serve government officials.” Public servants and party cadres also like to remind reporters that they, the reporters, work for the state. A journalist in Henan province confronted a local leader in 2011 about a tract of land marked for affordable housing that was instead turned into a high-end residential development. The official wheeled on the reporter: “Do you want to speak for the party or for the common people?” In 2009, a public servant from the cultural affairs bureau Tianqiao, a district of Jinan province, was accused of sexually harassing two female teachers during a banquet. When a journalist from Xinhua Net asked him about it, he pulled rank: “Isn’t Xinhua Net a cultural organization? I’m in charge of cultural issues. If you report this on Xinhua Net, I’ll shut it down.” A Shanxi official wins the category with his blunt response to a reporter who asked him about a corruption investigation in 2010: “If I weren’t corrupt, why would I become a government official?”

Losing one’s temper can draw mockery, too. A Yunnan mining boss and adviser to Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference was caught on video throwing a tantrum and destroying computer equipment when he missed a flight at the Kunming airport in February. Former President Jiang Zemin got ridiculed in 2000 for lashing out at an inquisitive reporter in Hong Kong, calling his questions “too simple, sometimes naïve.” It’s a testament to the control of Chinese media that this kind of incident only ever occurred in Hong Kong.

Expand the definition of “gaffe” beyond the verbal and you’ve got a whole range of political screw-ups, from sex-tape extortion to orgy pics to awful Photoshop jobs to wearing a Rolex one could never afford on a public servant’s salary.

If these gaffes have a common thread, it’s that they’re almost all 1) corruption-related, and 2) spoken by low-level officials. The higher up the totem pole, the less a politician says. It’s no coincidence that the most verbose, ostentatious Chinese leader of his generation, Bo Xilai, has left the building.

Biden’s tongue, meanwhile, has hardly kept him from the highest rungs of power. If anything, his career is testament to the fact that you can mess up again and again in American politics and still reach the top. And his gaffes, even at their most offensive, seem to stem from an earnest desire to communicate his feelings. As Biden’s plane lifted off from Beijing Thursday afternoon, it appeared that he’d successfully completed his visit without causing international incident.

“Innovation thrives where people breathe freely, speak freely,” Biden said in Beijing on Thursday. That’s where Joe Biden thrives too.

Christopher Beam is a staff writer at The New Republic.