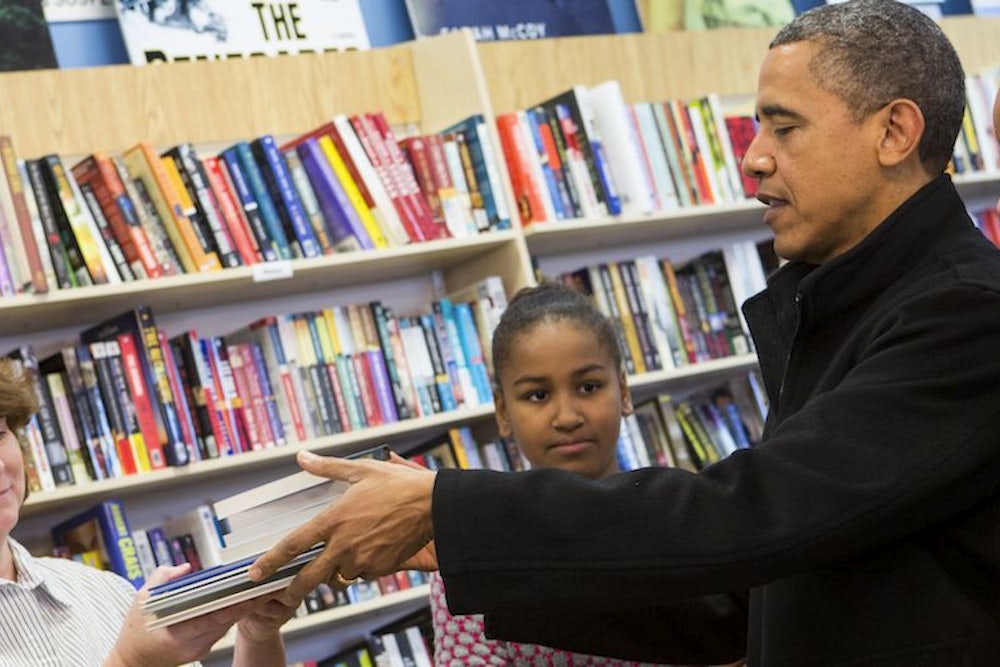

No one reaches the Oval Office without a great deal of admiration for the institution—and himself—so it’s unsurprising that sitting presidents favor the biographies of former presidents. George W. Bush set the Lincoln-biography bar high by reading 14 while in office and Barack Obama turned to Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals when making his own first-term cabinet decisions. While Lincoln’s successors can no doubt learn much from his tenure, the fixation on presidential biographies fails to challenge the imagination or empathy of the person holding what is the world’s most influential but also most insulated office. This is what makes Obama’s recent visit to Politics and Prose, a D.C. bookstore, so unusual: The books he bought included several novels.

The thread connecting the novels that Obama purchased is the notion that the intimate dramas of those existing far from the corridors of power are worth recording and reading. Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Lowland charts the divergent lives of two brothers from Calcutta. In The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini sets a story of personal guilt and obligation amid the chaos of Afghanistan. The Buddha in the Attic by Julie Otsuka gives voice to a chorus of Japanese mail-order brides brought to California in the early 20th-century. A Constellation of Vital Phenomena, my own novel, traces a handful of characters across war-torn Chechnya. (Before my head could get too big, my mom reminded me that Obama also picked up Harold and the Purple Crayon.)

The idea that fiction can capture the stories that fall through the cracks of history informed A Constellation of Vital Phenomena, which progresses across the two Chechen Wars of the 1990s and early 2000s. Much of what has been written about Chechnya has concentrated on Russian presidents and Chechen rebel commanders, but the stories that resounded most deeply in me, the stories that felt most urgent, were those of ordinary civilians. While soldiers and sheikhs are visible at the margins of A Constellation of Vital Phenomena, the novel is primarily about doctors, teachers, refugees, neighbors, parents, and children. People neither overly political nor overly religious, who have little say in the violence that fractures their lives. In effect, it’s a novel about those farthest from the source of political power yet closest to its consequences.

The version of Chechnya presented in popular culture is often distorted and grotesque—cartoonish thugs, leather-clad drug dealers, and turbaned terrorists—and a more nuanced view of a region is even more important now that it has returned to the public consciousness in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombings. As preparations for the 2014 Winter Olympics ramp up in Sochi just a few hundred miles to the west, Chechnya may again return to the headlines. And a more visceral sense of the conflict that dominated Putin’s early years in office might in some small way give insight into his current rule.

News footage from Aleppo, Baghdad, and southern Afghanistan plentifully displays the physical toll of other, ongoing civil wars. But I would argue that fiction is the medium best suited to capture the unseen devastation: The perversion of social obligations and loyalties, the fragmentation of the familial unit, the moral and spiritual degeneration of the self. When confronted with the facts of foreign atrocities, the experience is often consigned to the realm of the unimaginable. Fiction makes the unimaginable imaginable. And as unimaginable as the suffering produced by atrocity may be, the psychology of its perpetrators may be even more so. A novel can grant humanity even to those who act inhumanely, and by making men and women of monsters, it can offer not only a ground-level view of a particular conflict, but a descent into the substratum of human nature capable of the incomprehensible.

It is also a medium uniquely qualified to convey the inner rebellion against such devastation. The characters in A Constellation, while unremarkable by most standards of civic measurement, are extraordinary in their capacity to defy the despair imprinted into the private sphere by disastrous performances of political and military power. Through recognizable acts of compassion, most small, some large, they retain their humanity despite the geopolitical tides that might otherwise wash them of it. The characters are an amalgamation of research and imagination, and while traveling through the region after finishing the book, I repeatedly met them in ordinary people trying to move on with their lives. In Starogladovskaya, the curator of the only museum in Chechnya to remain open throughout the conflicts had recently completed much needed renovations. In Urus-Martan, a retired fighter had spent two decades hand-building a replica of his destroyed ancestral village in a lot behind his house. In Grozny, a government worker drove me to an empty field, asked me to take his picture in front of the flattened gravel that once had been his home, and then told me about his favorite Moscow nightclubs.

Their stories are the repercussions of policy decisions sketched out on legal pads and enacted by monolithic bureaucracies. It’s probably inevitable that these personal costs are subsumed within the abstractions of procedure. One only needs to look back to the previous presidency to find ample evidence that the dignity of the individual is quickly lost to leaders who transact at the scale of nations and populations. But those nations and populations are comprised of people whose experiences cannot be articulated as data points.

Novels are neither reportage nor textbooks. To read fiction strictly as a source of information misses the point that it conveys meaning resistant to quantification or aggregation. That meaning comes from the transcendent power of existing, for a few pages at least, inside the mind and soul of another person. No novel would simplify the decision to go to war, or to authorize a drone strike, because no good novel simplifies anything. But those well-educated in empathy are more likely to make more humane and compassionate choices, and what fiction can provide a leader is the ethically necessary complication of individuated experience. It’s impractical to imagine that novels would ever have the same effect as the intelligence reports that cross the presidential desk. But it is heartening that this president makes time for them.