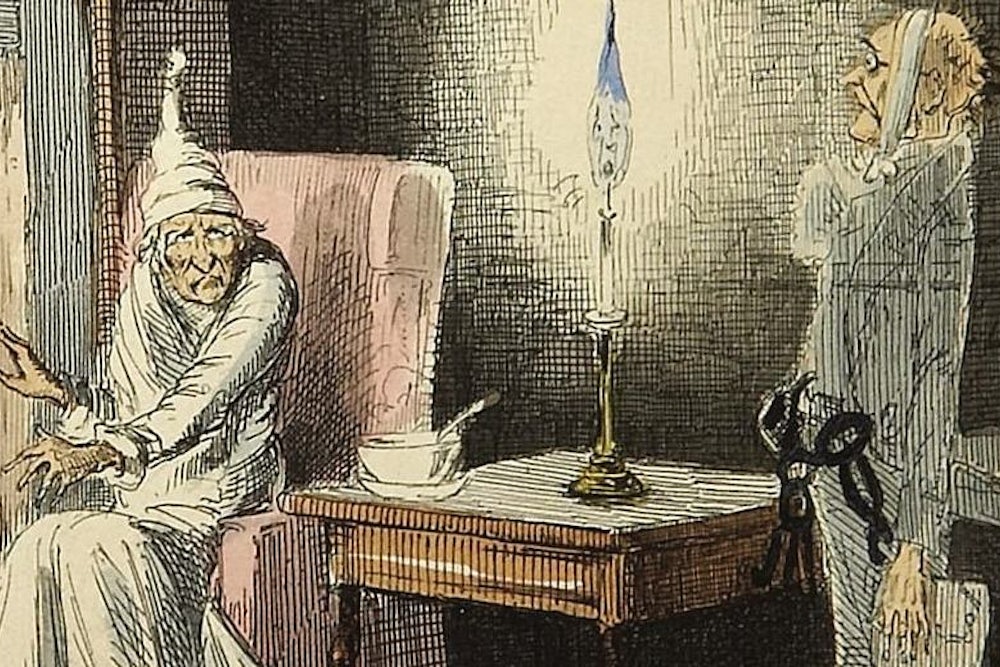

Now that Christmas is safely behind us, and the mob atmosphere of virtue and piety has evaporated; now that, in the post-holiday doldrums, the stacks of wrapping paper have removed themselves to their ghastly translucent plastic bags and the dead trees have begun, one by one, to lie across the sidewalk, forming their final, horizontal forest, in premonition of the universal fate—now, at gloomy last, something should be said on behalf of Christmas's eternal victim, the ever-persecuted Scrooge, who, for all his failings, got one large thing right.

It is true that, at Christmas parties, people should smile at one another—a point for Dickens, who inaugurated the anti-Scrooge campaign. Also, bosses should mumble a kind word to underpaid clerks, and wealthy businessmen should bestow alms, and childless uncles should make out wills in favor of their nephews, and so forth. Still, in the opening "stave," as Dickens calls his chapters, two portly gentlemen call on Scrooge & Marley, soliciting alms for the poor, and Scrooge refuses to donate, and his words and indignation ought not to be too quickly dismissed. "Are there no prisons?," says Scrooge. Everyone remembers this rejoinder. More: "And the Union workhouses? Are they still in operation?" And he adds: "I help to support the establishments I have mentioned—they cost enough; and those who are badly off must go there."

Dickens has presented Scrooge cruelly in this passage, and, by invoking prisons and workhouses, he has brought to mind the worst and ugliest of government agencies, in order to shine a warm light on his own preferred method for alleviating poverty, which is private charity. Prisons and workhouses are, even so, state-run social services, and everyone of a liberal sensibility ought to agree that a proper effort to cope with poverty is going to require government agencies more than door-to-door charitable campaigns. If only the oppressed proletarians of the Christmas Carol, the Cratchit family, possessed a full right to vote, which they do not, they would surely vote for government services, to be funded by the very mechanism to which Scrooge adverts, namely, taxation of wealthy persons such as himself.

The entire Carol turns on a plaintive note, which is warbled by the sickly and crippled Cratchit boy, Tiny Tim, who, a Spirit tells us, hasn't a ghost of a chance for survival so long as Scrooge remains tightfisted and cruel. This should remind us that, in regard to social problems and social service A Christmas Carol is, above all, a meditation on health care. Let us ask, then: should Tim's health and ability to survive depend on Scrooge's capricious impulses—his desire, one year, to keep his wealth to himself, or his Christmas recognition, the following year, that he ought to send a proper goose to his exploited clerk's impoverished family and ought even to offer Mr. Cratchit a raise? But, no, Tim's health care ought not to depend on the whims of Mr. Scrooge. The boy needs a reliable medical clinic or a public hospital—a large-scale government service, in short, like a prison or a workhouse, inscribed in law and supported by the whole of society, except devoted, in this instance, to pediatric medicine.

Dickens' understanding of questions like these was unreliable. He composed his Carol in a period, in 1843, when he was sunk into a mania of reactionary anti-Americanism, which means that, if you want to see the full nature of his ideas, you should peer into his books on American themes. He wrote two of those books, and they appeared immediately before and after A Christmas Carol—his American Notes in 1842, and his novel Martin Chuzzlewit in 1844. Those two books shudder at life in the ghastly United States. Dickens concludes that British immigrants to America are making a big mistake. The country seems to him dominated by hucksters promoting frauds—chiefly, the real estate scam perpetrated upon young Chuzzlewit, visiting from England, who ends up buying a swamp exuding a noxious, disease-bearing cloud. And yet, the portrait of real-estate frauds is merely Dickens' back-handed way of acknowledging that, in America, people are busy creating new businesses and are intent on building entire new cities and are actively investing and seeking everyone else's investment.

In young Chuzzlewit's fondly-remembered England, by contrast, only the crooks dream of doing anything new. To open a large and honest new business is beyond anyone's conception. Scarcely anyone even thinks of looking for a better job. Everyone hopes, instead, that moneybags will come along and, out of niceness, solve the problems of life. Office clerks aspire to spend their lives loyally serving a single wealthy employer. People with a rich relative devote themselves to scheming for the inheritance, especially in the case of young Martin's elderly grandfather, who is rolling in money. The grandfather is a bit of a Scrooge, though. And yet, good news!—Grandfather Chuzzlewit, just like Scrooge, turns out, by the end of the novel, to be a warm-hearted old codger, after all, and Grandfather takes proper care of the clerks and the relatives one and all, except for the scoundrels among them. And this, finally, is Dickens' ideal.

It is a dream of a society shaped like a Christmas tree. The impoverished and servile masses at the bottom are supposed to offer love and loyalty and labor to the handful of wealthy people at the top, and the moneyed handful are supposed to shed love and kindness and charity, like pine needles, on the underlings below. No one's place in society is supposed to change. Nor does anyone wish for a change. Everyone dreams of being patted on the head, or else of patting people on the head. These ideas were Thomas Carlyle's, and Carlyle was, in his political thinking, an utter reactionary, dedicated to the restoration of feudal hierarchies. Servility for the masses and grandeur for the privileged struck Carlyle as glorious. In A Christmas Carol you might fail to notice the feudal nostalgias at work because Dickens, being a genius, has known how to slather good cheer and sentimentality and wild images and love of life across the page. Still, if you squint, you ought to be able to see that master-servant hierarchies are his principal theme, and the Happy Ending consists of Scrooge finally coming to appreciate his lordly responsibilities to the wretched underlings, and the underlings' response of servile gratitude, such that Tiny Tim cries out, in an expression of love that extends even to his father's dreadful exploiter, Mr. Scrooge, "God bless us, every one!"

So it is left to Scrooge to explain that social services do need to be provided by the state, for which, being an upright citizen, he is willing to pay taxes. "Are there no prisons?" may not be the most appealing way of acknowledging the state's responsibility to society, just as "healthcare.gov" may not be the most appealing way of acknowledging the state's responsibility to guarantee health care to one and all. Still, "Are there no prisons?" and "healthcare.gov" do raise the issue, at least, of government action on behalf of society, which is more than can be said about people who call for pity, charity and niceness. Scrooge is the only person, ghost, spirit or entity in A Christmas Carol to make this valuable point. And I say, "One cheer for Mr. Scrooge—Hip!," and I say the same for healthcare.gov, and earnestly I hope that, one day in the future, occasions will arise to offer a second "hip!" and a hooray.