Twenty years ago what prophet would have cared to stake his reputation on a prediction that men then living would survive to see prohibition in force throughout America, immutably fixed by Constitutional amendment, enforcible by federal police regulations also provided for in the Constitution? It seemed impossible. Now it is a fact. The opponents of prohibition, to be sure, still talk of fighting it. They still plan to raise millions for a campaign of nullification. But soon they will recognize that they had better spare their efforts and save their cash. There is no undoing what has been done.

We cannot, however, dismiss the action from our minds with the simple acceptance of its irrevocability. The Constitution has not reached final shape with the eighteenth amendment. The same process by which the distilling and brewing and liquor selling interests have been wiped out may yet be employed to wipe out other interests as ruthlessly. Therefore the process is worth the study both of those who resist further change and of those who are eager for it. The first stage in that process was a natural adjustment to historical conditions peculiar to American colonial development. New England and the middle colonies were not adapted by soil and climate to wine culture. The colonists had not the patience and the industrial knack to produce good ales and beers, but their trading enterprises in the West Indies brought them unlimited rum and molasses, the raw material of rum. Drinking therefore tended naturally to drunkenness, and became early a moral issue, as it had never become in the countries of Europe, whence America had derived her morality. The westward movement of population carried with it the habit of hard liquor, as the most convenient form of transportation and production, and the moral issue followed after. So much for the preconditions of prohibition in America.

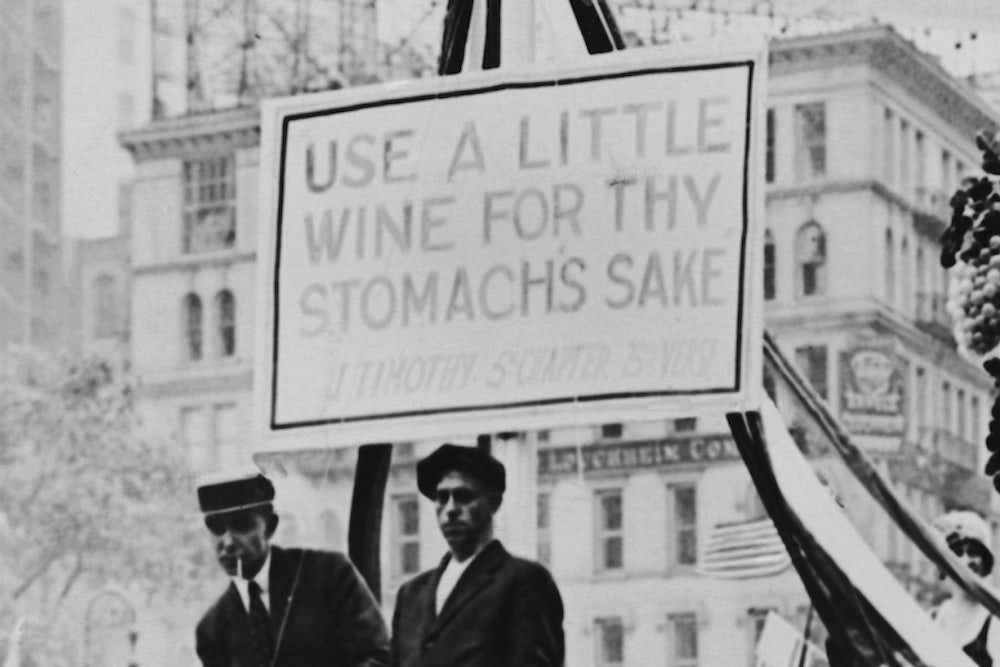

That, however, is only preliminary to an explanation of the success of the movement. Morality issues do not easily command the fervid support of the majority supposed to rule in a democracy. The history of non-enforcement in prohibition states gives color to the belief that scarcely anywhere have the convinced adherents of prohibition commanded a substantial majority. Nobody supposes that the remarkable progress of the eighteenth amendment through Congress and the state legislatures represents a corresponding fervency of purpose in the body of the people. Would a universal referendum on federal prohibition yield even a majority vote? We doubt it. But a majority is not needed to pass a law or a constitutional amendment if a clearly drawn moral issue is involved. No legislator, no man with political aspirations, can afford to have himself counted on the wrong side of a moral issue. He will vote on the side of morality, even if he considers it a bogus morality. For the memory of the moral is tenacious, and the vengeance of the moral is relentless, ruthless.

There is one more aspect of the struggle between prohibition and the liquor interests that deserves attention. Those interests, recognizing dimly that a political movement involving a definite conception of morality contained grave elements of danger, cast about for every means of defending themselves. They were driven straight into politics, and for generations played the game, unscrupulously, arrogantly, reaching into legislative bodies with bribes and favors, purchasing political organizations, corrupting the electorate, packing the ballot box. One would find difficulty in citing a single crooked nomination or election in which the liquor interests had no hand. Besides, they sought to control public opinion at its source, through the press. Everyone knows something of the influence upon editorial policies exerted through liquor advertising. Thus it was possible to stave off state prohibition measures or to render ineffective such measures as were forced through to enactment. But in securing such temporary gains the liquor interests building up against themselves a new moral issue. Many men who were not inclined to take too seriously the charge that liquor was destroying the physical manhood of the nation were fully convinced that it was implacable foe of the nation’s political integrity. True, there was a movement among the liquor men to reform themselves, to combat drunkenness, to clean up their political record. It came too late, and now the whole business has fallen with a crash, the lightest and least noxious liquors with the heaviest and most poisonous, the most decent and well-ordered “dinner with me” along with the most degraded and disorderly thugs’ hangout. Hundreds of millions of property values have been destroyed, with no distinction between the innocent holder of respectable brewery stock and the flashy brute who has fattened on the profits of illicit sales to brothels. In vain will any one protest in behalf of the widows and orphans whose property is wiped out, in behalf of the charitable and fiduciary institutions whose prosperity is compromised. The retort of the triumphant prohibitionist is that nobody can offer the please innocent investor in an immoral enterprise. And if it is urged that before the enactment of prohibition brewing and distilling were as lawful enterprises as any other, that brewing and distillery stock were capital like any other, equally clothes with the sanctity of private property, the prohibitionist replies that there is no such thing as the sanctity of private property in the average American’s mind. The sole title of property to inviolability, in the popular opinion that can make or unmake’ the Constitution, consists in morality and utility. The English, and the American legal profession trained in English habits of thought, may consider the vested interest as something in itself deserving of defence. The plain American does not. In his attitude on prohibition he has shown himself exactly as mindful of property interests of which his sense of morality does not approve as the Russian Bolsheviki. The Bolsheviki believe that property in land and manu- facturing capital degrades the masses and corrupts politics: therefore away with it. The American prohibitionist has similar views of the function of capital in breweries and distilleries. Away with it!

But American confiscation will stop there, will it not? Let us not be too sure of it. Consider for example the status of railway capital, not in law, where it is wholly secure, but in the public opinion that has so strikingly exhibited its power to remake the law. American railway policies in the early decades were tainted with force and fraud and destructive speculation. The conditions of a new country perverted railway policy, as earlier they had perverted the business of dealing in alcoholic beverages. The railways therefore raised up against themselves a moral movement, based on the formula that the service of transportation is a public service that ought not to be usurped by private profiteers. Whether that was a sound formula or not does not here matter. It was accepted, and is accepted, through wider circles, probably, than were in favor of federal prohibition twenty years ago. Because of the strength of the moral movement against them and its political consequences, control or blackmail, the railways went into politics, and in many states are popularly believed to have played a larger part in engineering crooked political deals than the liquor interests themselves. Like the liquor interests, the railways are conceived of as actively engaged in shaping public opinion through the press. True, the railways have of late given indications of reforming themselves. But are they going to be more successful than the liquor interests were with their “ light wines and beer “ movement?

That movement came too late. And there is ground for surmising that the railways will be too late in adjusting themselves to the public sentiment that has grown up against them. They know that the country is full of men who draw a sharp distinction between actual railway investment and watered stock, between the value of the plant created by the railway companies and the value of the right of way granted by the public. Yet the average railway man cries loudly for the right to earn on watered stock, on franchise values, as well as on track and rolling stock. He is willing to go into politics to establish that right. Under the Constitution he thinks he can secure its validation. Perhaps he can. But there are forces behind the Constitution that he had better take into account.

It is entirely within the bounds of probability that in their manoeuverings to get their properties back to private control, with the maximum possible improvement in their economic position, the railway owners will overplay their hands and consolidate against themselves the latent moral feeling that public service Is a public, not a private function. With a moral movement gaining head against them, the rest of the process is predictable. The railways are almost certain to occupy themselves more actively than ever with politics, and the more conscious they are of their danger, the greater will be their inclination to condone shady methods applied in their behalf. They will ally themselves with other interests menaced by legislative attack, such as profiteering monopolies, and thus draw upon themselves the whole force of the equalitarian attack. Put beyond the moral pale, they will find that no politician will dare openly to protect them. The way will then be clear for a constitutional amendment transferring the railways to the government, on such terms as the railways will not like.

To be sure, they will plead for the rights of the innocent investor, the widows and orphans, the charitable and fiduciary institutions holding railway securities. They will invoke the principle of the sanctity of private property. But the adoption of the eighteenth amendment has proved once for all that the American popular consciousness recognizes no such principle, when it conceives a moral issue to be at stake.

Prohibition without compensation; nationalization without compensation; the parallel is too close to be disregarded by men of affairs who are really practical and farseeing. There is still time for the railways to square themselves with public opinion by eliminating every claim that does not commend itself to fair-minded men as reasonable, by accepting the principle that future service, not vested interests from out of the past, are the only valid claim to reward. But it is not very probable that they will thus adjust themselves to the current of the times. They feel themselves clever, powerful, competent to win more than a democracy is really willing to grant them. That was the delusion under which the liquor interests labored twenty years ago.