By now, you may have heard about a new Republican health care plan—and how great it is. The proposal, which its authors call the “Patient CARE Act,” would hollow out the Obamacare infrastructure and replace it with a system more to conservative liking. There would be less government spending, lower taxes, fewer regulations—and yet, the sponsors promise, it would achieve roughly equal results when it comes to expanding insurance coverage.

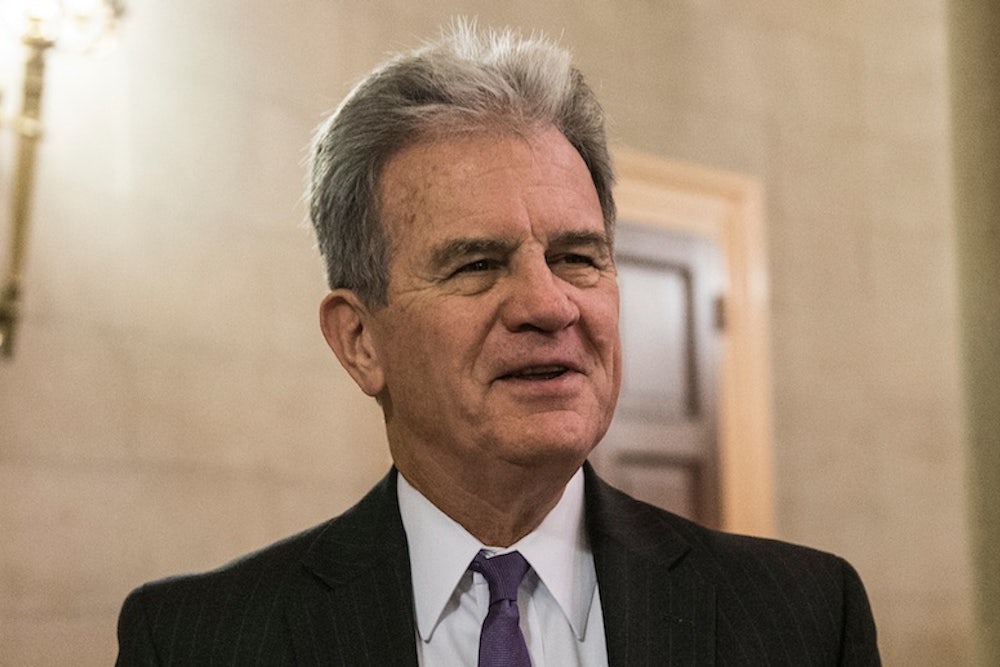

Conservatives are thrilled—not just because the proposal is a serious attempt to address the problem of unaffordable health care, but also because, in theory, it demonstrates the superiority of conservative approaches to health care. “One of the great liberal conceits of the age is that to extend insurance coverage to the uninsured and make sure the sick do not fall through the cracks requires the centralized political management of the health sector,” says a triumphalist editorial in National Review. “The great service that Senators Coburn, Hatch, and Burr have performed is to explode that myth.”

Sound too good to be true? That’s because it is.

Give those three Republican senators credit for proposing to replace Obamacare, rather than simply calling for repeal. And give them credit for putting together a real set of initiatives, rather than a flimsy set of slogans. The proposal includes a series of concrete, sometimes interesting changes to the status quo—among other things, wiping away Obamacare’s regulations on what insurance must provide; reducing the tax break for employer-sponsored insurance; undoing the expansion of Medicaid; and providing tax credits to help lower- and some middle-income people buy private insurance. (For more details, I highly recommend the write-ups by blogger/Duke Professor Don Taylor and Wonkblog’s Sarah Kliff.)

It would have been a lot more productive if these three senators, or any other Republicans, had been similarly constructive back in 2009—you know, when Congress was debating health care reform and Republicans had plenty of opportunities to put forward proposals. Still, coming to the conversation late is better than not coming at all. The flurry of new commentary on the Patient CARE Act, especially in conservative publications, is a sign of real deliberation on the right. The scheme even has some virtues that liberals can admire.

But to call this proposal a “plan” is also a little premature. Many of the details are vague and some appear to be in flux. Early in the week, Coburn and his advisers suggested their plan included a large reduction in the existing tax break for employer-sponsored insurance. Then, on Wednesday, they announced that the reduction would be much smaller. (An observant Dylan Scott of TPM noticed the shift.) That’s no small thing. That tax break is a bulwark of the existing system. The more you more reduce it, the more the system will change—for better or worse, or maybe some of both, depending on your perspective.

Lack of specificity isn’t a fatal flaw, at least at this early date: The white papers that eventually became Obamacare were pretty fuzzy, too. But it means the trade-offs and downsides of the Patient CARE Act aren’t readily apparent right now—just as Obamacare's weren't initially—and that claims about what it can accomplish are not always what they seem.

That’s most apparent when it comes to the core, most surprising statement the Patient CARE Act’s sponsors make—that, if implemented, it will reduce the number of uninsured Americans by roughly as much as Obamacare does. To back up this argument, the sponsors cite an analysis they commissioned from a new think-tank managed by a prominent conservative economist. It’s hard to know whether the analysis is correct: It’s based on assumptions the authors haven’t revealed and calculations from a model that sometimes produces very different results from those used by the Congressional Budget Office and other, more well-known analysts. But even if the projection is correct—that is, even if the end result is that the net expansion of coverage is roughly comparable—it’s likely a significant number of those people will have skimpy coverage. It's hard to say how many people would fall into this category, even roughly. But whatever their numbers, they would be exposed to much greater financial risk than they would be under Obamacare.

You can see this most obviously when it comes to childless adults with incomes below the poverty line (about $11,500 a year for a single person). Under Obamacare, these people are entitled to Medicaid, as long as their states choose to participate in the expansion. Medicaid has virtually no cost-sharing, which makes sense: Somebody at that income level can't deal with anything beyond token medical bils. Under the Patient CARE Act, these people would have to make do with a tax credit for buying private insurance. This is a change for the better, conservatives say, because people on Medicaid don't have great access to doctors. But according to Coburn’s website, the credit would be worth $1,560 a year for individuals between the ages of 18 and 34. The only policies available at that price would have significant coverage gaps or high out-of-pocket spending. (Either that, or they would have even worse access to physicians.)

Some people might take these policies anyway, particularly since the Patient CARE Act would allow states to enroll people preemptively (though with an option for individuals to refuse). As a result, analysts might count them as “insured.” But the people with this coverage would not have the financial protection most of us associate with insurance. And while the law as a whole would clearly give some people a better deal than Obamacare would—in part the "sticker price" of insurance would tend to be lower—overall the likely effect would be to provide less financial protection overall. “At the end of the day coverage expansion costs money—the uninsured have low income and even the most rigorous cost containment won’t make meaningful coverage inexpensive,” says Karen Pollitz, a senior fellow at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “With less for subsidies, tradeoffs are inevitable to make coverage cheaper in other ways—less inclusive, fewer covered benefits, fewer consumer protections.”

Another boast the Republican senators make is that their plan doesn’t raise taxes in order to finance the coverage expansion. Instead, it finances the coverage expansion primarily by reducing that aforementioned tax break for employer insurance. But Republicans would typically call such a change a tax increase. (In conservativespeak, ending a tax break is the same as raising taxes.) And one likely effect of that reduction would be to put pressure on employers to make insurance cheaper by any means possible.

Obamacare does this too, because—like the Coburn bill—it reduces the value of the existing tax break, albeit in a more indirect way. And the conservative method of reducing the tax break is actually preferable because it's more direct. But Obamacare’s reduction is relatively modest. The Coburn bill might envision a larger reduction. (Again, it's hard to be certain.) If so, employers would respond by reducing benefits, narrowing networks of providers, or some combination of the two. Most likely, some people would lose employer coverage altogether. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Premiums for this insurance would be lower and the money not spent on health insurance would, over time, show up in workers’ paychecks. But the disruptions to employer insurance would be precisely the sort of changes that Republicans say they hate about Obamacare.

The Republican senators make a big deal about the flexibility their proposal would offer, because the federal government wouldn’t be establishing a set of essential benefits that all plans must cover. And for people upset about what those requirements mean under Obamacare—for example, older men angry about the higher premiums that come with newly mandated maternity care—this will be a big plus. But "flexibility" also means that carriers could continue to sell junk insurance policies—and that people could continue to buy them, only to discover those policies don't provide the coverage they need. For many people, the Patient CARE Act really would mean cheaper insurance, just like the proposal's champions say. But that's because there'd be less security. “It doesn’t work if you’re poor or if you’re sick—other than that, it's ok," quips Jonathan Gruber, the MIT economist and Obamacare architect.

Flexibility would also mean that insurers could use benefit design to scare away people with high risks, since people with chronic conditions are unlikely to buy plans that won’t cover treatment for their diseases. And speaking of people with medical problems, the Republican senators say their plan would help people with pre-existing conditions. But the guarantee of insurance would exist only for people who maintain their coverage—something that, without sufficient financial assistance, some people would not be able to do.

To be clear, whether you think the Patient CARE Act is worse or better than the Affordable Care Act depends on how you value the pros and cons of each. Roughly speaking, Obamacare provides more financial protection to more people, but with more government spending and a narrower range of options in the insurance market. Conservative alternatives would provide less financial protection to fewer people, but with less government spending and a wider range of options in the insurance market. Reasonable people can disagree on which approach does the most good. It comes down to priorities and judgment.

But the authors of the Patient CARE Act and many of their allies are acting as if conservatives have some magic elixir for health care problems—a way to provide the same kind of security that the Affordable Care Act will, but with a lot less interference in the market and a lot less taxpayer money. It's all the goodies of liberal health care reform, they imply, but without the unpleasant parts. They're wrong.

Note: This item has been updated.