The following article contains NSFW images.

We are having a bit of a bicoastal bohemian moment. Jess, the dreamily uncategorizable San Francisco painter and collagist who died in 2004, is the subject of an engrossing exhibition at the Grey Art Gallery in New York. And Peter Hujar, the New York photographer who died of AIDS in 1987 and whose strikingly saturnine achievement is every bit as difficult to define, is featured at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco. Both Jess and Hujar were romantic outliers, and well before their deaths they were underground avant-garde legends in the cities they loved. I am heartened to see them embraced by a new wave of artists and critics. Jess and Hujar responded to the tsunami of mid-to-late-twentieth-century art by becoming deep-sea divers, discovering strange and wonderful visions far below American culture’s roiling surfaces.

Art, love, and friendship are magnificently tangled in the lives of these men, their paintings, collages, and photographs at once freestanding achievements and mirrors held up to the fascinations and enchantments of a pre-Silicon Valley San Francisco and an as-yet-ungentrified Lower East Side. The Fraenkel Gallery show, “Peter Hujar: Love and Lust,” features the artist and his friends and lovers, among them the artist David Wojnarowicz, many stripped naked; the images are unvarnished, intimate, by turns supercharged and tenderhearted. The Jess show—“An Opening of the Field: Jess, Robert Duncan, and Their Circle”—unites a remarkable selection of Jess’s paintings with work by his life partner, the poet Robert Duncan, as well as pieces by a couple of dozen friends in San Francisco’s mid-century bohemia. These exhibitions are about elective affinities both artistic and affective, the invention of self as a dialogue between nature and culture. For Jess and Hujar a man can surely be the artist’s lover and simultaneously the artist’s muse, much as one imagines the handsome Jess was for Duncan. The musings and amusements these artists offer are personally tailored, cut from their own bespoke bohemian patterns, so that they subvert not only straight society, but also any standard issue theory about homoerotic or homosocial experience or the counterculture or the avant-garde.

The postmoderns have only begun to catch up with Jess’s idiosyncratic modernism, which is rich, layered, opulent, and paradoxical. You feel the sensuous pull of an older, grittier San Francisco—the San Francisco found in Arnold Genthe’s photographs of Chinatown, of sailors exploring the dance halls and bars of the city’s Barbary Coast, of Victorian gingerbread houses that are all the more alluring for being a little past their prime. What Jess called his Paste-Ups, uncoiling, spiraling, labyrinthine collages composed of figures and other elements clipped from magazines and a variety of sources, have begun to fascinate younger artists who are on a mixed-media spree. With a dozen Paste-Ups and several dozen paintings, Jess can lay claim to being one of the immortal eccentrics of American art, maneuvering mythopoetic images (his fairy tales for adults), bejeweled colors, and volcanic eruptions of pigment. If there is one painting of Jess’s in the Grey Art Gallery show that is a sure twentieth-century masterpiece, it is The Enamord Mage: Translation #6. Here Duncan presides in a cottage he and Jess shared at Stinson Beach, the Limoges-enamel atmosphere keyed to an art nouveau hanging lamp, the glass formed into ruby red cherries and leaves in a variety of greens. There are books on a shelf (including The Zohar in five volumes), a lit candle, plants, pictures, a glorious jumble rendered (or perhaps reimagined is a better word) in perfervid hues. Everything is real and unreal, naturalistically drawn and hyperbolically colored, a domestic hallucination. Duncan once wrote of Jess that art “is a recreation of the World, a play ground, or the creation of a New World in the world.” This is precisely the impact of The Enamord Mage, with the familiar world renewed, much as Jess and Duncan, announcing themselves a married couple in mid-century San Francisco, made their own New World in the world. ("An Opening of the Field" was organized at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento by Michael Duncan and Christopher Wagstaff, both essential advocates and interpreters of Jess’s work. For those who want to see more, the Tibor de Nagy Gallery has a concurrent show.)

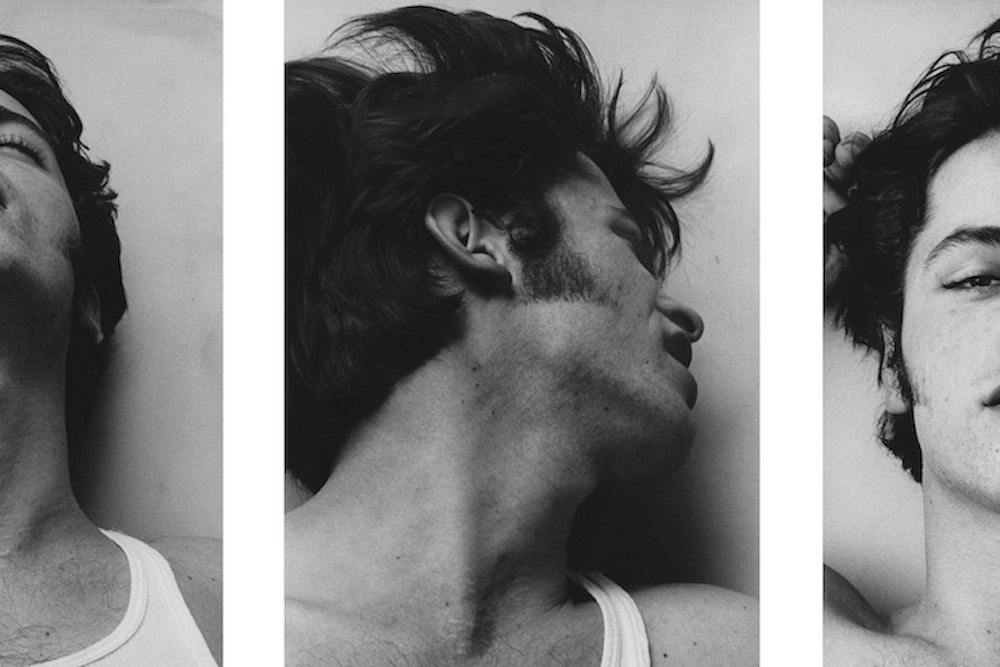

If Jess’s orchestrations of extravagant fin-de-siècle images and beautifully foggy effects evoke the lost San Francisco of everybody’s dreams, the astringent blacks and whites of Hujar’s photographs will forever be associated with the crumbling walk-ups and lofts and coldwater flats of the East Village and the Lower East Side where Hujar lived and worked. Although I’m afraid I will miss Hujar’s show at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, I have before me the catalogue, and the photography books published by Fraenkel are among the most beautiful made today. Hujar—whose velvety night scenes of New York have been the subject of memorable exhibitions in New York and San Francisco—takes a pile of risks in the work gathered in “Love and Lust.” Frequently photographing solitary men engaged in intimate acts, his approach is empathetic rather than voyeuristic, a search for the private poetic imagination that is not always entirely separable from the public pornographic imagination. By no means do all of these photographs convince; some are too hot, some too cold. But in the finest included here, Hujar takes his place among the great photographers of human intimacy, up there with E. J. Bellocq in his studies of New Orleans prostitutes and Brassaï in his chronicles of the nighttime pleasures of 1930s Paris. With Daniel Schook Sucking Toe, Hujar explores an experience of the beauty of one’s own body that is simultaneously inward-turning and outward-flowing, bringing to mind Alfred Stieglitz’s ravishing photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe, the muse in a state of musing, except that the shadow of reticence shading Stieglitz’s studies of O’Keeffe has been replaced by the frank, challenging gaze of a late-twentieth-century young man. In a pitch-perfect catalogue essay, the critic Vince Aletti, a close friend of Hujar’s, tells how Hujar photographed a boyfriend of Aletti’s, revealing him not “just naked,” but also “open and present.” That’s true of all the finest photographs in this show.

With Hujar and Jess, the relationship between life and art is as intimate as can be, the life feeding the art in the most immediate ways. A risk is the risk of sentimentality, a too easy and undifferentiated indulgence in one’s own emotional weather, a collapse of the distance that art’s order provides. What keeps sentimentality at bay in the finest of both artists’ work is an imperturbability I associate with the rigors of the bohemian life, the effort to find one’s own utterly unconventional place in the world that calls all easy assumptions into question. Speaking in the late 1960s, John Ashbery, who wrote with great feeling about Jess’s art, said that for the avant-garde, acceptance had become all too easy. Ashbery argued that artists who wanted to find something new had to “fight acceptance”—and that that involved fighting something in oneself. Both Jess’s hedonism and what might be called Hujar’s hedonistic asceticism involved a search for levels of experience that were unexpected, surprising, pure. Their stylistic daring—Jess’s baroque or mannerist voluptuousness, Hujar’s classical forthrightness—cannot be separated from a hard-won individualism. That the work of both artists speaks to a new generation is a sure sign that even in the age of the selfie, artists are looking for ways to reinvent the self.