The Long Voyage: Selected Letters of Malcolm Cowley, 1915-1987 Edited by Hans Bak, Foreword by Robert Cowley (Harvard University Press)

Among the hallucinatory flashbacks in Ernest Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” as the dying writer Harry relives his past amid an African safari gone awry, are memories of the Great War juxtaposed with the self-indulgent silliness of Americans in Paris during the ’20s.

Later he had seen the things that he could never think of and later still he had seen much worse. So when he got back to Paris that time he could not talk about it or stand to have it mentioned. And there in the café as he passed was that American poet with a pile of saucers in front of him and a stupid look on his potato face talking about the Dada movement with a Roumanian who said his name was Tristan Tzara, who always wore a monocle and had a headache ...

In 1951, Philip Young, at work on the first critical biography of Hemingway, asked the distinguished critic, literary historian, and poet Malcolm Cowley if the potato-faced poet might have been Ezra Pound.

Cowley, who had known Hemingway in Paris before serving as literary editor of The New Republic during the 1930s, seemed the right guy to ask. Cowley’s “Portrait of Mr. Papa” had appeared in Life two years earlier, and his best-known book, Exile’s Return, which appeared in 1934, was an ambitious attempt to convey the temperament and trajectory of what Gertrude Stein named the “Lost Generation,” consisting of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, and Cowley himself, among others. It was a generation lost, Cowley explained, “because it was uprooted, schooled away, almost wrenched away from its attachment to any region or tradition. It was lost because its training had prepared it for another world than existed after the war (and because the war prepared it for nothing). It was lost because it chose to live in exile. It was lost because it had no trustworthy guides, and had formed for itself only the vaguest picture of society and the writer’s place in it.”

As Cowley noted, members of this predominantly Ivy League contingent (Cowley’s poems were first published in book form under the unintentionally comic title Eight More Harvard Poets) drove ambulances (Hemingway) and munitions trucks (Cowley) in World War I, apprenticed themselves to Parisian literary fashions, and returned to the United States just in time for the Crash, when many of them, including Cowley himself, embraced communism—and “trustworthy guides” such as Marx and Stalin—as a bulwark against fascism and as the right fix for America’s desperate economic ills.

Marco Wagner

Marco Wagner

Always eager to guide younger writers, Cowley assured Philip Young that Hemingway’s potato-faced poet wasn’t meant to be Pound. Cowley surmised that it might be Matthew Josephson, a poet-critic and close friend of Cowley’s “whom Ernest doesn’t like too well.” Cowley guessed wrong. Just before Hemingway published “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” in Esquire in August 1936, he had made a slight change to the following sentence: “And there in the café as he passed was Malcolm Cowley with a pile of saucers in front of him and a stupid look on his potato face....”

Why did Hemingway make this late revision? In another book on Hemingway, published in 1987, two years before Cowley’s death, Kenneth Lynn, a prominent “Neon Conservative” (as Cowley referred to his antagonists during the Reagan years), suggested that Cowley, as literary editor of The New Republic, “was in a position to retaliate against writers who insulted him.” It seems more likely, however, that Hemingway decided to keep the potato-faced poet’s identity purposefully vague, as representative of a pervasive tendency in American poetry—right and left, in Eliot and Pound but also in Cowley and Josephson—to ape foreign fashions, hence Tarzan with his monocle.

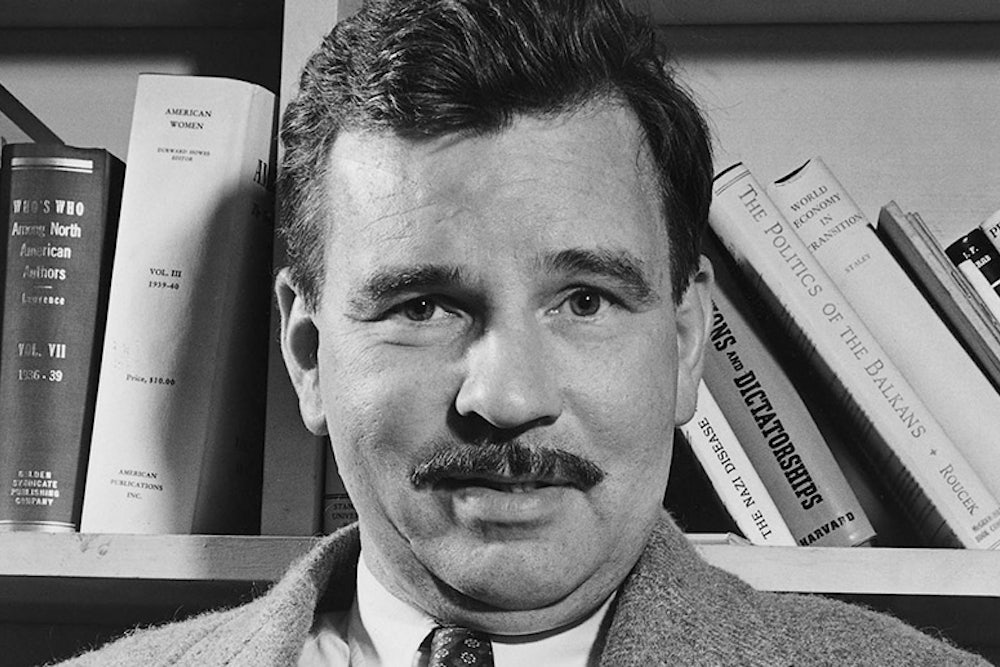

Born in 1898 on a farm in western Pennsylvania, and a longtime resident of rural Connecticut after his stirring sojourns in Paris and New York between the wars, Malcolm Cowley brought the literary swagger of the 1920s to everything he did.1 “Cowley’s face had kept the faint smile of defiance,” Alfred Kazin recalled, “the swashbuckling look and military mustache of intellectual officers in the First World War, the look of gallantry in sophistication that one connected with the heroes of Hemingway.”

Cowley played the rugged individualist in his literary and political opinions—“one of the roughs,” as Whitman, one of his literary heroes, called himself. But there was always a tension in his temperament between the loner and the joiner, the emphatic “I” and the generational “we.” “Wherever Cowley moved or ate, wherever he lived,” Kazin wrote a little cruelly, “he heard the bell of literary history sounding the moment and his own voice calling possibly another change in the literary weather.”

Cowley did not come from a privileged background, and always thought of himself as something of an outsider, an exile, looking in. The son of a homeopathic doctor and adherent of Swedenborg, he had grown up on the outskirts of Pittsburgh, with forays for hunting and fishing to the dilapidated boyhood region a few hours to the east described in his beautiful poem “Blue Juniata”:

Farmhouses curl like horns of plenty, hide

scrawny bare shanks against a barn, or crouch

empty in the shadow of a mountain. Here there is no house at all—

The Cowleys, he told Kazin in a letter, “were regarded as being quite strange, if harmless, and too poor to clothe themselves properly.” Among his father’s patients were the family of the critic Kenneth Burke, a classmate and lifelong friend. Cowley attended Harvard on scholarship, where he was “almost but not completely an outsider,” starved in Greenwich Village, went to France, again on scholarship, before starving again as a copywriter and proofreader for an architectural catalog. His position at The New Republic was his first real job.

One of the many surprises in the Dutch scholar Hans Bak’s generous selection of Cowley’s letters, The Long Voyage (very long, at eight hundred pages, though representing only a fraction of Cowley’s epistolary output), is how seriously Cowley, a poet and critic best known for his championing of lonely American eccentrics from Hawthorne and Whitman to Kerouac and Ken Kesey, embraced movements such as Dada and its exotic outgrowth of Surrealism, before committing himself to communism. “The Communist adventure itself is one of Surrealism’s unlikeliest non-sequiturs,” John Ashbery once wrote. But for Cowley, Dada always had a political, even revolutionary edge. From the vantage point of Dada, the established world had “to be fought, insulted, or mystified,” he insisted.

Cowley’s chosen means for insult doesn’t seem daringly original. On Bastille Day 1923, “eaten with the desire to do something significant and indiscreet,” he punched in the mouth the proprietor of the Montparnasse café La Rotonde, who had a reputation for treating American women as prostitutes. For this “significant gesture,” as Cowley’s Dadaist colleagues liked to call it—but significant of what, exactly?—Cowley spent the night in a Paris jail before his admiring friends bribed and bailed him out. After two years in France—pursuing research on Racine, of all people—Cowley returned to America, where he married his artist wife, Peggy, and determined to make his way as a freelance writer.

Cowley wrote fluently and was a skilled networker, quickly making the leap from little magazines to The New Republic.2 Edmund Wilson, the literary editor at the time, hired him as his assistant in 1929, three weeks before the Crash. When Wilson took a leave from the magazine to travel around the country and write about the effects of the depression, Cowley succeeded him. For younger writers coming of age during the 1930s, Cowley, smoking his pipe in his seersucker suit, seemed like an establishment figure rather than a man of Dadaist bravado. Kazin remembered the waiting room outside Cowley’s The New Republic office as a sort of breadline for unemployed writers, with Cowley, “a tolerant smile on the face which so startlingly duplicated Hemingway’s handsomeness,” handing out assignments or cash from the sale of books unsuitable for review.

While it is often said that Cowley directed the back pages of the magazine in a resolutely communist direction—toward “a sophisticated literary Stalinism,” in Kazin’s mordant phrase—Cowley’s cultural interests during the 1930s were broad, and certainly not limited to proletarian novels and agitprop poetry. “I’d never sacrifice a literary admiration to a political opinion,” he claimed in 1937. “It would much more likely be the other way around.” He maintained friendships and accorded reviews to people quite hostile to communism, reactionary Southern writers such as his close friend Allen Tate, a self-styled “agrarian” who claimed to be more hostile to capitalism than Cowley was. “You and the other Marxians are not revolutionary enough,” Tate told Cowley, “you want to keep capitalism with the capitalism left out.”

In The New Republic of the mid-’30s Cowley wrote vividly, if dolefully, about the Gone with the Wind phenomenon, and in another article praised the very different “plantation novel” Absalom, Absalom!. He chided Yeats for excluding Wilfred Owen’s war poetry from The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, and pointed out what was right (contemporary diction) and wrong (hexameters don’t work in English) in Edna St. Vincent Millay’s translations of Baudelaire. Always on the lookout for promising new writers, he published the eighteen-year-old John Cheever’s first piece of writing, about being kicked out of prep school, and the poetry of John Berryman, Muriel Rukeyser, and Theodore Roethke. He published his close friend Hart Crane’s gorgeous last poem, “The Broken Tower,” a love poem, as it happened, to Cowley’s estranged wife, Peggy, with whom Crane, a gay poet trying to go straight, was traveling at the time of his suicide in 1932.

Meanwhile, with some of the same cavalier generosity with which he handed out assignments and petty cash to the supplicants in the waiting room, Cowley, who never formally joined the Communist Party (very few prominent writers did), allowed his name to grace the mastheads of various communist-front cultural organizations, and took a leading part in one of them, the League of American Writers. His prolonged allegiance to Russia, long after the show trials in Moscow had shocked and soured most of his friends, remains awful and unexplained. Of the purges of “Trotskyites” and their staged confessions, Cowley wrote, unbelievably, to Edmund Wilson:

I went so dead on the Moscow trials that I can’t get around to answering your letter.... I think that their confessions can be explained only on the hypothesis that most of them were guilty almost exactly as charged. With that guilt as a start, they could be made to confess still other things if that seemed desirable....

“What in God’s name has happened to you?” Wilson responded.

When the music finally stopped for Cowley, after the Russo-German pact of 1939 finally sealed his disenchantment with Stalin, he found that his comrades had long since taken their seats. He wrote forlornly to Wilson in February 1940:

I am left standing pretty much alone, in the air, unsupported, a situation that is much more uncomfortable for me than it would be for you, since my normal instinct is toward cooperation. For the moment I want to get out of every God damned thing. These quarrels leave me with a sense of having touched something unclean.

Cowley resigned from the League of American Writers, and was predictably accused of treachery by both communists and self-proclaimed patriots. In his defense—excruciating to read—Cowley gestured vaguely to a “lassitude that I don’t know how to explain,” and compared his embrace of communism to a religious conversion followed by loss of faith. The truth is probably closer to Wilson’s diagnosis—that political positions had, for Cowley, about the same weight as his significant gesture in punching the proprietor of the Rotonde. “I think politics is bad for you because it is not real to you,” Wilson told him presciently.

And so Cowley’s long rehabilitation began. In 1941, Archibald MacLeish generously but unwisely finagled a job for him as an information analyst in the newly formed Office of Facts and Figures—Cowley wrote the text for the “Freedom of Want” section of FDR’s Four Freedoms speech. But Texas Congressman Martin Dies, chair of the red-baiting House Committee on Un-American Activities, denounced Cowley, claiming that he had belonged to seventy-two communist-front organizations—an exaggerated number, though Cowley wouldn’t have been able to give the correct figure. Cowley resigned in 1942. More helpful was a generous grant from the Bollingen Foundation (funded by Paul Mellon’s first wife Mary), which allowed Cowley to hole up in Connecticut for five years and write what he wanted to write.

Cowley’s past was dredged up periodically. In 1949, a particularly bad year, Cowley had to deal with Robert Lowell’s mania-induced claim that Yaddo, the writers’ retreat in Saratoga where Cowley served as a director and was a yearly visitor, was a nest of Russian spies; he had to testify, twice, at the Alger Hiss trial, the result of an ill-advised lunch he had once had with Whittaker Chambers (he took no position regarding Hiss but swore that Chambers was a liar); and he had to put up with the organized resistance, at the University of Washington, to his appointment as a visiting professor there.

During the cold war, Cowley avoided politics and embraced what he called “my favorite trade of revisionist.” He revised his books, in effect revising his life along the way. “I hate to write and love to revise,” he wrote in 1951 in the revised version of Exile’s Return, while “divesting it of its radical politics,” as Bak delicately puts it. He revised and reissued his poems with headnotes that rendered them, in a parallel to Exile’s Return, representative of a generation rather than an individual voice. The poems themselves sometimes have a generic quality. A passage from “This Morning Robins” (a revision of “Yesterday Snow” from The New Republic in 1936), “How many springs outlived, how many suns / from clouds outburrowing like April woodchucks ...,” sounds a bit close to Hart Crane’s opening lines from The Bridge: “How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest / The seagull’s wings shall dip and pivot him.”

The revising habit spread. Helping to reissue Fitzgerald’s work for Scribner’s, he persuaded himself that some notes in the Princeton archives represented Fitzgerald’s second-guessing conviction that Tender Is the Night would have been more effective with a chronological order of events. Instead of opening with Rosemary’s first meeting with the psychoanalyst Dick Diver’s family on the Riviera, followed by a flashback to Diver’s beginnings, the novel might be streamlined by reversing the two sections. The book was reissued according to Cowley’s restructuring, to lasting confusion. The Portable Faulkner, a collage of selections from novels and stories, which Cowley pieced together in 1946, at a time when Faulkner’s work was mainly out of print, also adopts a chronological approach; the book, quite brilliant in its way (and sparing readers the difficulty of tackling forbidding books such as Absalom, Absalom!—Cowley considered Faulkner’s “murkiest novels” overvalued), helped spark a Faulkner revival, leading (though not quite as directly as Cowley’s admirers claim, since French admirers like Sartre and Camus were also instrumental) to the Nobel Prize three years later.

More enduringly, Cowley made the claim that Whitman’s 1855 Leaves of Grass—all but unknown a hundred years after its publication—was a better book than its later, expanded versions of 1860 and 1891–1892. “I feel myself on a crusade for an unadulterated early Walt,” he wrote to Daniel Aaron in 1959. While Cowley’s preference may have owed something to his discomfort with Whitman’s “adulterated” celebration of homosexuality in the Calamus poems (later editions were “mixed with the ambiguous doctrine of male comradeship,” he wrote in his introduction to the reissued poem), his championing of an earlier Whitman has had a lasting effect—no serious reader now reads Whitman without taking the 1855 Leaves and its lyrical preface into account.

None of these revisionist activities amounted to a coherent theory. Indeed, theoretical ideas were Cowley’s weakness. It is sometimes a little embarrassing when he launches into arguments about the nature of literature. He found difficult books annoying, had little patience for Proust, Joyce, or Gertrude Stein—even Henry James made him impatient—and he was particularly hostile to opaque poetry. If he belonged to a literary movement, it wasn’t Dada or fellow-traveling Marxism but rather the school that Van Wyck Brooks and Lewis Mumford had more or less founded, and to which Edmund Wilson had given a brilliant and decisive push, what we would now call the careful “contextualization” of literary works in their biographical and historical setting.

To this approach—still the dominant strand in much of the best literary reviewing—Cowley added a stirring idea that he probably owed to Kenneth Burke (a brilliant and eccentric critic and thinker), or perhaps they had developed it together over years of regular correspondence: the conviction that literature can usefully serve, in Burke’s phrase, as “equipment for living” by providing a paradigm (the way a proverb like “don’t cry over spilled milk” does) for recurring historical and personal situations. The applications of literature can be unpredictable, as Cowley knew from his own profound understanding of the reach of American writers abroad. When he wrote to Margaret Mitchell to ask her about the international reception of Gone with the Wind, he informed her that Sartre had told him of the novel’s huge popularity in France during World War II, not for ideological reasons (the French were hardly supporters of slavery) but because of the portrayal of a people surviving occupation by a foreign power.

Cowley earned, many times over, his status as the grand old man of American letters. Did anyone do more to establish the current canon of the major writers of the twentieth century? Did anyone do more than Cowley, as the indefatigable consulting editor for Viking, to identify new talent among the following generations?3 (It is stirring to find Cowley championing Kerouac, another voice of a generation, even as he advised him to revise his torrential prose: “You have a very fast curve, hard to hit, but it doesn’t always go over the plate.”) Did anyone work harder behind the scenes of influential organizations (the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Yaddo, countless book prizes, and so on) to support writers in need and reward deserving achievement?

“Our lives that seemed a random and monotonous series of incidents are something more than that,” he observed in his charming book The View from 80; “each of them has a plot.” The plot of Cowley’s own life breaks in two. The period of “confused transition” he had ascribed to the Lost Generation turned out, for him, to be the 1930s, when, from his office at this magazine, his influence was highest, before he had to reinvent himself, in one of those second acts that Fitzgerald had said American writers were denied.

What Cowley achieved after his seeming disgrace—when, in Daniel Aaron’s sardonic words, “the intelligentsia who turned against the party before Malcolm Cowley did singled him out as the classical ‘horrid example’ of the ‘Stalinist’ stooge or muddled pseudo-Marxist”—is remarkable. During the sometimes excruciating decades that followed, he turned the many themes of lostness, so eloquently described in Exile’s Return, into something found and reasonably triumphant. If he revised—“Time ... for a hundred visions and revisions,” as Eliot said—more often than not his revisions improved on the original. He ultimately belonged, like Fitzgerald and Hemingway and Faulkner, to what his friend Hart Crane called “the visionary company,” and not as a fellow traveler but as a full member.

Christopher Benfey is a contributing editor at The New Republic and the author, most recently, of Red Brick, Black Mountain, White Clay: Reflections on Art, Family, and Survival (Penguin).

- Cowley was at his best when he detected a kindred swagger among contemporaries like Andre Malraux, whom he admired as “a soldier of fortune who risked his life in the revolutionary cause.” Malraux’s Man’s Fate struck Cowley as “a philosophical novel in which the philosophy is expressed in terms of violent actions” and “a novel about proletarian heroes in which the technique is that developed by the Symbolists of the Ivory Tower.” In both phrases, Cowley could be speaking of his own, somewhat divided literary allegiances.

- Cowley could be harsh in his reviews but he was never cruel. His “Robert Frost: A Dissenting Opinion” takes issue with the selfish speaker of “Two Tramps in Mud Time,” who lets the unemployed jobseekers “walk away without a promise or a penny,” and concludes that Frost, in contrast to Emerson or Thoreau, is the poet of “the diminished but prosperous and self-respecting New England of the tourist home and the antique shop in the old stone mill.” But Cowley was appalled by the “notoriously unfair” reviews Randall Jarrell inflicted on poets. “Why, if he whipped them with a whip soaked in brine, kicked them in the kidneys, held lighted matches to their sexual organs, he could scarcely cause them more pain” (p. 292).

- Cowley taught fiction-writing at Stanford on several occasions, beginning in the late 1950s. One of his classes, during the fall of 1960, included Larry McMurtry, Peter S. Beagle, and Ken Kesey. Tillie Olsen studied with him at Stanford as well. Hans Bak notes that this was “an exceptionally talented group of emerging writers.” True enough. But their “emergence” depended a great deal on discerning supporters like Cowley, who recognized their potential and helped shepherd their careers. (p. 469, 522, 547)