The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism by Doris Kearns Goodwin (Simon & Schuster)

It is no secret that we are living in a second Gilded Age—another era, like the first, of corrupt rule by plutocratic elites. What is less clear is how to end it. Without assuming that one can draw simple “lessons” from history, we might begin by exploring how we ended it the first time, by discovering how reformers redeemed democracy—or at least some semblance of it—from crony capitalism. How did the Gilded Age become the Progressive Era?

At the core of that transformation was a widespread revulsion from plutocracy, a desire to promote a larger public interest—a reassertion of commonwealth against wealth as a standard of value. A hundred years ago, this agenda animated millions of Americans. A clear majority of the electorate considered themselves “progressive.” But the word was elastic enough to contain everyone from Eastern patricians to Nebraska wheat farmers and small-town attorneys in Georgia. Walter Lippmann was a progressive, but so were William Jennings Bryan and Pitchfork Ben Tillman. The progressive notion of “the public” was as shadowy and ubiquitous as the contemporary politician’s notion of the “middle class.”

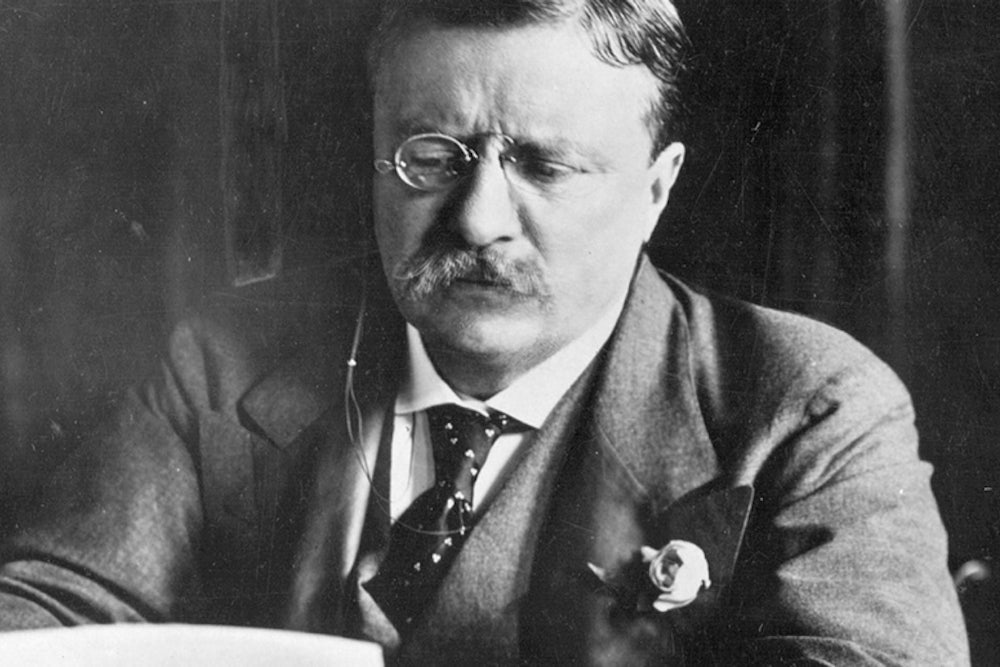

The most popular contemporary version of progressive reform—at least inside the Beltway—puts Theodore Roosevelt at the center of events, leading insurgent Republicans against the party’s Old Guard, consolidating progressive gains during his presidency, and passing the baton to his successor William Howard Taft—and then, frustrated by Taft’s persistent conservatism, running for president as the candidate of a new Progressive Party and losing to another progressive, Woodrow Wilson, in 1912. This is the story retold by Doris Kearns Goodwin in her thoroughly mediocre book. The narrative is easily assimilated to contemporary centrist wisdom about the need for a bipartisan Third Way, an alternative to the endless bickering of Republicans and Democrats. On this view, progressive reform was commanded by metropolitan elites with a sense of noblesse oblige—Roosevelt epitomized the type—men who translated the public interest into the emerging idiom of managerial expertise, who found neutral technicians to staff the regulatory commissions that would (the reformers hoped) cleanse capitalism of its excesses. This benign managerial vision, according to the centrist narrative, is what we need to revitalize contemporary public life.

No one can deny the importance of noblesse oblige to a healthy political culture, or discount its steady disappearance in our own time. But a focus on Roosevelt and the Republican Party obscures the origins of progressive reform, as well as the most persistent sources of its strength. The effort to tame unbridled capitalism originated not in the mind of Theodore Roosevelt but in the rural Midwest and South—in the Populist movement of the 1890s. It was absorbed and carried forward by the populist wing of the Democratic Party. Under Bryan’s leadership, the Democrats took a left turn in 1896; they remained committed to a progressive agenda until World War I. Bryan epitomized the rural roots of reform: like other populist progressives, he proposed ending special privilege through statutory regulation (passing laws against corrupt or monopolistic practices and jailing the people who violated them) rather than discretionary regulation (giving expert commissions the power to decide how best to manage corporate malpractice). Populist progressives recognized from the outset that an expert commission could be captured by the very industry it was meant to regulate. They were more realistic about power than the managerial progressives.

They were also more religious. Bryan and other populist progressives derived much of their fervor from a Christian vision of a Co-operative Commonwealth, a Kingdom of God on Earth that would emerge in all its glory after they had prepared the way for Christ’s Second Coming. This was back in the day when Jesus was a Democrat. The populist heritage accounted for the egalitarian impulses that continued to animate progressive reform well into the twentieth century, especially in the South and the Midwest. This was the era when the most popular socialist newspaper was published in Girard, Kansas and the leading socialist politician (Eugene Debs) hailed from Terre Haute, Indiana. For a while, even socialism was as American as cherry pie, a legitimate part of the egalitarian coalition that dominated American politics during the decades before World War I.

Yet a major part of that coalition was the Jim Crow South. The coexistence of conflicting social visions—of racial hierarchy and economic equality—underscores the tragic paradox of the progressive tradition in twentieth-century America. The reforms that created the foundations for an American version of the welfare state—first in the Progressive Era, later during the New Deal—were dependent on keeping race off the table. When Jesus was a Democrat, all the Democrats were white. This may help to explain the persistently awkward fit in American politics between the ideals of racial and economic equality, despite their indisputable interdependence. As the nineteenth century became the twentieth, progressive reformers began a long tradition of ignoring the complementarity of race and class privilege. Ever since, for critics of status quo power arrangements in America, talking about class has been a way of not talking about race—and vice versa.

None of these issues appear in The Bully Pulpit. This sprawling book is very much a Washington insider’s view of the Progressive Era. Progressivism, in Goodwin’s account, is a movement made by Big Men—Presidents Roosevelt and Taft, accompanied by a retinue of senators, congressmen, and judges. Ordinary people are offstage, except for cameo appearances when they are brought on to cheer or to jeer. Besides movers and shakers in the Republican Party, the only Americans with major roles in this account of the era are star reporters for McClure’s and other reformist magazines. Despite occasional nods from Goodwin, Democrats and other populist progressives are almost invisible. Their votes are necessary but they are taken for granted. Bryan and the progressive Wisconsin Republican Robert La Follette appear through Roosevelt’s and Taft’s eyes as dangerous radicals. There is some acknowledgment of populistic moral fervor, mostly through quotations of Roosevelt’s rhetoric of righteousness. But the dominant drift of reform, in Goodwin’s account, is secular, pragmatic, and managerial.

Despite its bulk, Goodwin’s book tells us next to nothing about the cultural and social setting of progressive political struggles. No attention is paid to the impulses that assured Roosevelt’s success (while it lasted): the fascination with virility and vitality, the reverence for action as an end in itself. These notions were pervasive during the early twentieth century among middle- and upper-class white men—among the electorate, in other words. Roosevelt embraced activism to escape depression after his first wife’s death in 1884. “Black care,” he wrote, “rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.” The strategy suited his temperament, but it also resonated with widespread popular longings. Mania was the mood of the moment, a recoil from the specter of “neurasthenia”—the immobilizing depression that observers called “the disease of the age” among the white-collar classes. It is impossible to understand the appeal of T. R.’s relentless activism without taking these cultural currents into account.

Nor is it possible to understand the broader social significance of progressive reform without at least gesturing toward its rural populist origins. One would think, from reading Goodwin, that the achievements of the Progressive Era arose entirely from the confluence of executive leadership and journalistic fashion. The grassroots are invisible here. Goodwin blithely ignores a huge scholarly literature that has accumulated over recent decades, which explores the local and vernacular roots of progressive reform. She provides no new interpretation and no new information, covering a lot of ground well tilled already by political historians and biographers. Plowing through her undistinguished prose, one is tempted to ask: why was this lumbering production unleashed upon the world?

As befits a PBS presidential historian, most of Goodwin’s book is a joint biography of Roosevelt and Taft. Their story recalls an archaic time when people of privilege felt public responsibility, when “special interests” referred to crony capitalists (rather than teachers’ unions), when reform meant taming the market rather than conforming to its discipline. Taft and Roosevelt were linked by their elite backgrounds—the Porcellian Club, the Skull & Bones Society—and by their paternalistic sense of noblesse oblige. But there the resemblance ended. Taft was cautious, judicious, fair, generous, kind, slow to anger, eager to overlook slights; his enormous heft, topping out at 332 pounds, reinforced the impression that he was a man given to sustained deliberation. Roosevelt, by contrast, was restless and rarely still—“pure Act,” in Henry Adams’s words. He was also opportunistic, convinced of his own righteousness, manipulative toward people who could advance his interests, and vindictive toward actual and imagined enemies. Above all, he despised indecision and inaction as signs of weakness. For Roosevelt, doing something—even something mistaken and destructive—was always better than doing nothing. Goodwin’s book is stuffed with personal details about both men’s lives and larded with long quotations from their correspondence, and the overall effect is fatiguing but decisive: Taft comes across as a more humane leader and a more companionable character.

Along with the story of the friendship, rivalry, and reconciliation between two presidents, Goodwin claims to capture a particular aspect of the zeitgeist, which her subtitle evokes as “the golden age of journalism.” Professional historians are allergic to golden ages, of course; but here the phrase may well be justified. Without question, investigative reporting flourished in the Progressive Era as it has rarely done before or since. Journalism was more about the pursuit of truth than the appearance of balance. The center of the ferment was Samuel McClure, who founded the magazine bearing his name and who shared with Roosevelt (and many other contemporaries) what Goodwin calls “the compulsive drive to stave off depression through ceaseless activity.” McClure hired Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, and Ida Tarbell (among other talented writers) and gave them enough space, time, and money to produce convincing accounts of corruption—legislatures bribed wholesale, city governments riddled with graft. Part of the appeal of McClure’s to middle- and upper-class readers was that it treated labor unions (whose power was minuscule to nonexistent at the time) as if they were as great a threat to the public interest as monopolistic corporations. Then as now, sensible centrists liked to believe that they were about to be crushed between upper and nether millstones. But McClure’s also published devastating reports on concentrated power, such as the series that became Tarbell’s History of the Standard Oil Company and Steffens’s Shame of the Cities—reports that inspired anti-trust litigation and urban reforms.

Roosevelt’s relation to investigative journalism was always ambiguous. He cultivated the press assiduously, agreeing to keep reporters posted on evolving plans and policies if they promised (in Goodwin’s words) “never to ‘violate a confidence or publish news that the President thought ought not to be published.’ ” Here was Roosevelt at his most manipulative, but Goodwin does not see any threat to independent journalism in the bargain that he proposed: inside dope in exchange for self-censorship. Roosevelt also corresponded with Tarbell, Steffens, and Baker, even inviting Baker to provide him with background information on policy controversies. But by 1906, when David Graham Phillips’s The Treason of the Senate revealed the pervasive power of corporate privilege in the nation’s highest deliberative body, Roosevelt began to fear that his party’s control of Congress would be undone by journalistic zeal. At a Gridiron Club dinner, he unleashed a tirade against “the man with the muckrake,” who was so preoccupied with cleansing politics of corruption that he failed to see the signs of vigor in American public life. In a burst of presidential ambivalence, the “muckraker” was born—sometimes performing public service but eventually annoying even would-be reformers by “insisting upon nothing but the dark side of life,” as Roosevelt complained to the humorist Finley Peter Dunne.

Roosevelt’s willed optimism has survived to our own time, while investigative journalism has been relegated to the margins of public life. Here is another difference between the Progressive Era and the present: in those days, journalists revealed publicly what insiders knew privately, and readers were naïve enough—or serious enough about the responsibilities of citizenship—to be outraged by the revelations. If the reining in of capitalist excess depends on this kind of relationship between the press and the public, our second Gilded Age may last much longer than the first.

From youth to middle age, Roosevelt’s and Taft’s lives took opposite physical trajectories—Roosevelt’s toward strenuosity, Taft’s toward obesity. Roosevelt began as an asthmatic weakling and made his life a parable of upper-class male regeneration. Taft’s early life, though no more economically privileged, had been less emotionally demanding. By the time he graduated from Cincinnati Law School, young Taft seemed on his way to a comfortable bourgeois existence.

But as a rising young attorney, Taft soon found himself cast in the role of standard-bearer for the good-government wing of the Republican Party—a rising star whose name, despite his youth, always surfaced when judicial appointments were discussed. At about this time he met Nellie Herron, the fourth of eleven children in a status-striving family. Keeping her distance from the debutante scene, she taught at a boys’ private school and presided over a local salon on Saturday nights. Will Taft was a participant, and he was smitten. After weeks of importuning, Taft persuaded Nellie to marry him.

This was a momentous choice for his career. Nellie was ambitious for both of them, reluctant to resign herself to the quiet life of a judge’s wife in Ohio. Whenever her husband faced a choice between judgeships and political appointments, she always pushed for the political option. Nellie enjoyed being a public man’s wife, and she was good at it. This was not just a matter of fashionable self-display; for her husband, she was an editor, an adviser, and a confidante. After a steady ascent through the Ohio judiciary, to the post of Superior Court judge, Taft was offered the job of U. S. solicitor general in 1890; Nellie was thrilled and Taft reluctantly accepted.

Theodore Roosevelt had just arrived in Washington himself. He had begun his public career as a New York state assemblyman, then accepted the Republican nomination in the New York City mayor’s race in 1886. One of his opponents was the homegrown radical Henry George, whose important book Progress and Poverty had articulated an early warning against the rising inequalities spurred by the spread of industrial capitalism. Roosevelt would have none of it. To him, talk of inequality smacked of foreign radicalism. As he told George, “If you had any conception of the true American spirit you would know we do not have ‘classes’ at all on this side of the water.” By 1886, Roosevelt had already distanced himself from the language of class, as he would do throughout his career. Three weeks after the election, he married Edith Carow. Soon afterward he was appointed civil service commissioner.

The job of maintaining a merit system against a spoils system was perfectly suited to a patrician reformer such as Roosevelt. It also cemented his friendship with Taft, whom he met soon after the new solicitor general arrived in town. The two both lived near Farragut Square and often walked to work together, talking excitedly of government by the competent. But soon more urgent topics asserted themselves, as the depression of the 1890s brought mass unemployment and even mass starvation into view. As always, one man’s depression was another’s opportunity. Sam McClure, who had already made a fortune by syndicating well-known authors, picked the Panic year of 1893 to launch his new magazine and pack it with Midwestern progressive staff writers. “They talked the Mississippi Valley vernacular,” the Kansan William Allen White recalled. Ray Baker caught their common commitment when he vowed “to look at life before I talked about it: not to look at it second-hand, by way of books, but so far as possible to examine the thing itself.” The distrust of second-hand knowledge, the preoccupation with locating the thing itself: this was the naïve but necessary epistemology of investigative journalism.

The journalists’ pursuit of the real resonated with Roosevelt, the man of action who became New York City police commissioner in the mid-1890s. “The peculiarity about him is that he has what is essentially a boy’s mind,” observed Joseph Bishop of the New York Evening Post. Throughout his adult life, people were struck by Roosevelt’s boyishness. Whether this trait would limit his ability to govern was at first a matter for conjecture. By the time he returned to Washington as assistant secretary of the Navy, the evidence was becoming clear. Ida Tarbell was appalled by his conduct during the crisis over the explosion of the battleship Maine, when he raced about the corridors of the Navy Department “like a boy on roller skates” in his excited anticipation of war. Roosevelt shrewdly enlisted the celebrity journalist Richard Harding Davis into his regiment of Rough Riders, and Goodwin relies uncritically on Davis’s worshipful account of Roosevelt’s charge up Kettle Hill (known to posterity as San Juan Hill). More skeptical observers saw “the commander rushing his men into a situation from which only luck extracted them,” as Newton D. Baker, secretary of war under Wilson, summarized the scene.

Whatever the actual circumstances, the “San Juan Hill Affair” made Roosevelt’s career. He returned from the war to run successfully for governor of New York and proceeded to mesmerize reporters with two press conferences a day. He also established a solid record on labor issues—an eight-hour day for state employees, maximum hours for women and children in industrial work, more factory inspectors. Roosevelt was beginning to move beyond the “good government” formulas of civil-service reform.

But he still referred to Bryan as “the quack.” The dismissal was rooted in Roosevelt’s class prejudice and imperial fervor. Bryan was leading the anti-imperialist opposition to acquiring the Philippines—and anti-imperialists were, in Roosevelt’s words, “little better than traitors.” Questioning the patriotism of one’s opponents in foreign-policy debate became an established practice that has survived to our own time. So have two other Rooseveltian rhetorical tics: conflating the nation and the individual, and confusing physical courage with moral courage. By 1900, he had become a regular on the banquet circuit, warning that “if we shrink from the hard contests where men must win at hazard of their lives and at risk of all they hold dear, then the bolder and stronger peoples will pass us by, and win for themselves the domination of the world.” This sort of talk elevated Roosevelt to the vice-presidency; it also had calamitous longer-term consequences for public discourse in America. National regeneration, often defined in crude physical terms, became a staple of imperial rhetoric. Ever since Roosevelt, advocates of military intervention abroad have embraced his demented dualism, telling Americans they could either “stand tall” or “cut and run.”

Taft was immune to that sort of bluster. He had spent the 1890s as a circuit court judge in Ohio, establishing a reputation as a moderate arbitrator of the struggle between labor and capital. He had not paid much attention to foreign policy, nor had he been keen on acquiring the Philippines, but once the thing was done, he believed that the United States should step up to its responsibilities. For the McKinley administration, therefore, he made the ideal choice for governor general of the islands. American soldiers had bogged down in a brutal counter-insurgency war against Filipinos who insisted on the independence they thought the Americans had promised them. Unlike the combative General Arthur MacArthur (Douglas’s father and the commander of the occupying forces), Taft sought rapprochement with the “little brown brothers.” Gradually the Filipinos reconciled themselves to the American occupation.

The episode epitomized Taft’s talent for conciliation—not one of Roosevelt’s strengths. Still Roosevelt attempted it, after ascending to the presidency in the wake of McKinley’s assassination. The problem was that his combativeness combined with his grandiosity to create muddled policy. At first, he appeared to declare independence from Wall Street. He dismissed the parvenu creed of money worship with patrician hauteur; he challenged the arrogance of men such as J. P. Morgan, who treated the president of the United States as just a “big rival operator.” By bringing an anti-trust suit against the Morgan-controlled Northern Securities Company, Roosevelt began to demonstrate that the interests of Wall Street and Washington were not identical. This achievement, however modest, was a departure from the dominant assumptions of Gilded Age public policy.

Yet it was undermined by his weakness for pop-evolutionary teleology. Like many among the privileged and powerful, Roosevelt assumed that he was on the cutting edge of history and could discern its future trajectory. So from the outset he distrusted the more sweeping anti-trust stance of the Democrats as a product of nostalgia for a pre-industrial past that could not be recovered. Morgan and other leading corporate executives contributed heavily to his re-election campaign in 1904, and Roosevelt began to make distinctions between “good” trusts and “bad” trusts. While his Justice Department still occasionally brought anti-trust suits, Roosevelt focused more and more attention on managerial approaches to policy, asserting the government’s authority to regulate railroad rates and monitor the ingredients of consumer goods. And Roosevelt’s extraordinary popularity was never merely a matter of legislative achievement. His vitality satisfied powerful yearnings in his audience. So did his plain speech. He established his rapport with crowds by coining aphorisms: “speak softly and carry a big stick ... a square deal for every man, great or small, rich or poor.” Ordinary people found his energy animating.

Roosevelt also cultivated cordial relations with the McClure’s writers, who were at their peak influence during his presidency. He was most comfortable with Baker, whose critiques of union corruption counterbalanced hostility to capital by reminding middle-class readers of the nether millstone. Tarbell was more independent and unpredictable. She disapproved of Roosevelt’s connivance with a covert business syndicate in the seizure of the Panama Canal Zone, but helped his drive for railroad regulation by documenting Standard Oil’s illegal rebates to their preferred carriers. Steffens was equally determined to maintain his independence. Roosevelt admired him warily, but the two men disagreed about the possibility of collaborating with entrenched power. Roosevelt was always more sanguine than the skeptical Steffens. “I’d rather make our government represent us than dig the canal; the President would rather dig the canal and regulate railroad rates. So he makes his ‘deal’ with the speaker and I condemn it,” Steffens wrote in 1906.

By then Phillips’s The Treason of the Senate had been published and Roosevelt, fearing a general backlash against Republicans, condemned the muckrakers. Yet he still alluded to their findings, without acknowledgment, to defend his policies. In 1907, when the stock market plummeted and Wall Street blamed the “Roosevelt Panic” on his allegedly anti-business rhetoric, Roosevelt attributed the crash to “certain malefactors of great wealth” whose misdeeds had been exposed. He himself, he said, was “responsible for turning on the light,” but not for “what the light showed.” The investigative journalists he courted and relied upon to mobilize public opinion had somehow disappeared.

By this time he was thinking about his successor. He had brought Taft into his cabinet as secretary of war. The appointment delighted Nellie and gave Taft opportunities to put out fires set by Roosevelt’s imperial policies. When some Cubans proved less than satisfied with the American version of independence, Taft persuaded them to lay down their arms and submit to a temporary provisional government with himself in charge—backed by a contingent of Marines. Nellie was giddy as she set sail from Norfolk to join him: “For the first time in my life I feel as if we were actually ‘going to war,’ ” she said. Such were the vicarious pleasures of imaginary battle. Given Nellie’s outlook, it should come as no surprise that she was “bitterly opposed” (in Goodwin’s words) when Roosevelt proposed nominating Taft to the Supreme Court. She had her eye on the White House.

Roosevelt came to share her ambitions for her husband, at least ambivalently. Despite his delight in the presidency, he continued to insist that there would be no third term, and that Taft would be the legitimate heir. Things would be quieter, but a progressive agenda would still advance. He was right about that, but politics is never merely about policy. Despite his considerable achievements, Taft paled by comparison with the magnetic Roosevelt. Warnings appeared early on, when during a Roosevelt boom at the Republican convention delegates tossed a four-foot Teddy Bear about the hall. Soon afterward a cartoonist portrayed Taft as Billy Possum, and the Taft campaign thought they saw an opportunity. They persuaded a toy manufacturer to create a Billy Possum character, but it looked like a giant rat. Children cried and fled when they saw it. This was not a propitious sign: Taft would never be able to play the game of mass-media politics the way Roosevelt could. Still, his progressive credentials were strong: he supported a progressive income tax and the direct election of senators (who up to then were chosen by state legislatures), though these measures were not on the Republican platform. And he managed to win as Roosevelt’s chosen successor.

No one knows how Taft would have fared if Nellie had not been silenced by a stroke ten weeks after the inauguration. In the face of her affliction, Taft appeared like “a great stricken animal,” his aide Archie Butt observed. The president sat by his wife’s side by the hour, patiently urging her to pronounce simple words. But still he had to govern, and his style differed markedly from Roosevelt’s. Taft did not wield the “big stick through the press,” as reporters noted, to prod legislators. Instead he depended on personal appeals and private meetings. He discontinued weekly press conferences. He never found any way “to properly utilize” the sympathetic White, Goodwin says, or Tarbell either. Taft himself confessed he was “derelict” in his use of the bully pulpit.

The fundamental flaw in Taft’s administration—if one can call it a flaw—was his failure to manage the news. He simply did not have Roosevelt’s knack for creating and manipulating publicity. Yet his policy accomplishments were equally—if not more—substantial than his predecessor’s. His Department of Justice brought twice as many anti-trust suits as Roosevelt’s and won some high-profile decisions, culminating in the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911. He further strengthened federal control over railroad rates and brought telephone and telegraph companies under supervision by the Interstate Commerce Commission. Under his leadership, Congress passed laws publicizing campaign contributions, before and after elections, established a Bureau of Mines to monitor conditions in that murderous business, and chartered a postal savings bank for people of modest means, with deposits guaranteed by the United States Treasury. It was by any measure a record of solid progressive accomplishment. Yet somehow he always came off looking like a conservative.

The Ballinger-Pinchot Affair typified this pattern. Taft supported the secretary of the interior, Richard Ballinger, when he was under accusation of capitulating to extractive industries’ demands for broad access to public lands. Among the chief accusers was Roosevelt’s protégé, Gifford Pinchot, the chief forester. Taft’s refusal to fire Ballinger provoked the permanent enmity of the progressive press, which still yearned for the colonel’s return. Even though nearly all the charges against Ballinger turned out to be false, and even though the Taft administration protected nearly as much public land in four years as the Roosevelt administration had done in seven, the Ballinger-Pinchot Affair stuck in the public mind as a victory of “predatory interests” over the people.

Reformers’ faith in Taft had already been weakened by his acceptance of the Payne-Aldrich Tariff, which continued to favor the industrial Northeast over the rest of the country, and by his failure to challenge the tyrannical rule of the speaker of the House, Joe Cannon. Roosevelt had been as inert as Taft on these matters, but as John Phillips of McClure’s observed, Roosevelt’s policy record “ mattered little to the insurgents”—what mattered was his “crusading spirit.” And by 1910, Roosevelt was ready for his next crusade.

He announced it in Osawatomie, Kansas, in a speech called “The New Nationalism.” Roosevelt charged that “the great special business interests too often control and corrupt the men and methods of government for their own profit. We must drive the special interests out of politics.” The Square Deal, it turned out, did not go far enough. The rules of the game had to be changed: direct primaries; laws forbidding corporate political contributions; new income and inheritance taxes; new laws regulating child labor and women’s work, enforcing better working conditions, providing vocational training. It was a sweeping agenda that aimed to enlarge government, cleanse it of business influence, and put it in the service of the public interest.

Yet it left open the question of how to define the public interest. Roosevelt himself lurched all over the lot, seeking to mollify his conservative critics while firing up the progressives. This became apparent when Taft’s Justice Department brought an anti-trust suit against U. S. Steel’s acquisition of Tennessee Coal and Iron—a merger Roosevelt had approved as a quid pro quo for Morgan’s assistance in the banking crisis of 1907. Roosevelt was outraged. According to Goodwin, his “indictment of Taft’s anti-trust policy was perfectly timed to catch the shifting current in public opinion” toward regulating monopolies rather than breaking them up. But there is simply no evidence for this supposed shift. Americans by and large remained deeply suspicious of monopoly power. Roosevelt derided Taft’s apparent determination “to break up all combinations merely because they are large and successful.” The job of controlling monopolies belonged to the federal executive, he claimed, not the courts. As Goodwin observes, “more conservative Republicans, frightened by the Osawatomie speech, found comfort in the Colonel’s carefully reasoned position on trusts.” What she calls careful reasoning was little more than warmed-over business apologetics combined with techno-determinist assumptions about the inevitability of bigness. Roosevelt was not a serious thinker; he was, as La Follette observed, a “switch engine” that “[ran] on one track, and then on another,” depending on what served his interests at the moment.

On certain foreign-policy matters, however, Roosevelt would never compromise. When Taft proposed a treaty with Great Britain that would submit all disagreements to arbitration—including those involving “national honor”—Roosevelt was livid. It was as if a man whose wife “has her face slapped” in his presence chooses to “go to law about it, rather than forthwith punishing the offender,” he wrote. This was a puerile taunt, comparable to a CNN anchor’s asking Michael Dukakis in 1988 whether he would oppose capital punishment for a man who raped his wife. Once again conflating the individual and the nation, Roosevelt turned policy disagreements into tests of personal manhood.

In February 1912, a few days before he formally announced his run for the presidency, Roosevelt lurched again, urging that judicial decisions should be subject to popular recall. The position outraged Taft, a fervent constitutionalist who was firmly attached to the separation of powers. For Roosevelt, Taft’s opposition to judicial recall made him an oligarch who vested his hope in the courts—“a special class of persons wiser than the people.” The fight was on.

Roosevelt’s friends and family were vexed by his decision to run. He took the high ground. “The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena,” he said, “whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly, who errs [but] ... who spends himself in a worthy cause.” So the Republican campaign pitted this manic activist against a different sort of man. According to Archie Butt, who served in both presidencies, Taft was “in many ways ... the best man I have ever known, too honest for the Presidency, possibly, and possibly too good-natured or too trusting or too something on which it is hard just now for a contemporary to put his finger, but on which the finger of the historian of our politics will be placed.” The tactical problem, as Taft recognized, was that Roosevelt had declared war on Taft, and “in a war,” as Baker observed, “the chief thing is to fight.” Goodwin continues, “The temperate Taft was ill-equipped to take up arms.”

Roosevelt, in contrast, could not stop attacking. Having won a majority of the primaries, he nevertheless faced defeat at the Chicago convention, since most delegates were chosen by the state party organizations. Roosevelt decided to make one last dramatic (and foredoomed) appeal to the convention. No candidate had ever done this before. The New York state boss William Barnes was bemused: “Undignified as it is, and impotent as it will prove to be, its chief interest lies in the disclosure of the mania for power over which Mr. Roosevelt has no control.” Even his old friend Elihu Root admitted that “he is essentially a fighter, and when he gets into a fight he is completely dominated by the desire to destroy.” When the fight was over, his friendship with Taft was in shreds, though they managed to meet and reconcile in 1918. It is somehow fitting that Roosevelt spent his last years railing against Woodrow Wilson’s timidity while Taft became chief justice of the Supreme Court. Both men stayed in character to the end.

At their most capacious, the progressives aimed to tame wealth in the name of commonwealth. That social democratic ideal lost luster during the 1920s, and then regained it from the New Deal through the Great Society. But in the last forty years, as American politics showed signs of straining (however inadequately) toward greater gender and racial equality, the progressive vision of a more economically just society disappeared from public discourse. Only recently has it returned, but often in blurred and barely recognizable forms.

Consider Barack Obama’s pilgrimage to Osawatomie in December 2011, when he set out to conjure the spirit of Theodore Roosevelt. It was, many claimed, the speech his supporters had been yearning to hear for three years. Obama warned that the dream of equal opportunity for all had peaked in the prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s, and now it was dying. He traced its decline to the “you’re on your own” economics of the Republican Party. He pledged fairer taxes and stricter regulation of investment banking. He promised to revive equality through government support for entrepreneurship and its basis, education, which would underwrite “innovation.” In sum, the rhetoric of social democracy evaporated in a technocratic haze. Despite frequent nods to Roosevelt, Obama never made the New Nationalist case for a federal government purged of business interests and dedicated to the public good. But how could he? After a forty-year diet of free-market globaloney, no one in the press corps—except maybe for a few muckrakers—would have had the faintest idea what he was talking about.

Jackson Lears is editor of Raritan and is writing a history of animal spirits in American cultural and economic life.