The Age of Nothing: How We Sought to Live Since the Death of God

by Peter Watson

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 624pp

Culture and the Death of God![]()

by Terry Eagleton

Yale University Press, 264pp

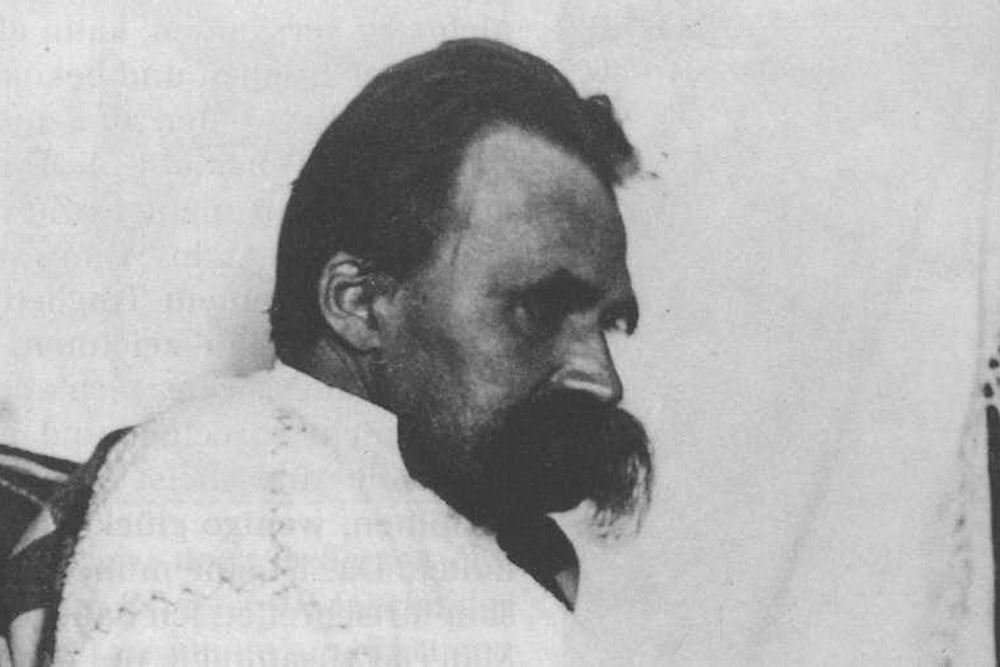

There can be little doubt that Nietzsche is the most important figure in modern atheism, but you would never know it from reading the current crop of unbelievers, who rarely cite his arguments or even mention him. Today’s atheists cultivate a broad ignorance of the history of the ideas they fervently preach, and there are many reasons why they might prefer that the 19th-century German thinker be consigned to the memory hole. With few exceptions, contemporary atheists are earnest and militant liberals. Awkwardly, Nietzsche pointed out that liberal values derive from Jewish and Christian monotheism, and rejected these values for that very reason. There is no basis—whether in logic or history—for the prevailing notion that atheism and liberalism go together. Illustrating this fact, Nietzsche can only be an embarrassment for atheists today. Worse, they can’t help dimly suspecting they embody precisely the kind of pious freethinker that Nietzsche despised and mocked: loud in their mawkish reverence for humanity, and stridently censorious of any criticism of liberal hopes.

Against this background, it is refreshing that Peter Watson and Terry Eagleton take Nietzsche as the central reference point for their inquiries into the retreat of theism. For Watson, an accomplished intellectual historian, Nietzsche diagnosed the “nihilist predicament” in which the high-bourgeois civilization that preceded the Great War unwittingly found itself.

First published in 1882, Nietzsche’s dictum “God is dead” described a situation in which science (notably Darwinism) had revealed “a world with no inherent order or meaning”. With theism no longer credible, meaning would have to be made in future by human beings—but what kind of meaning, and by which human beings? In a vividly engaging conspectus of the formative ideas of the past century, The Age of Nothing shows how Nietzsche’s diagnosis evoked responses in many areas of cultural life, including some surprising parts of the political spectrum.

While it is widely known that Nietzsche’s ideas were used as a rationale for imperialism, and later fascism and Nazism, Watson recounts how Nietzsche had a great impact on Bolshevik thinking, too. The first Soviet director of education, Anatoly Lunacharsky (who was also in charge of state censorship of the arts and bore the delicious title of Commissar of Enlightenment), saw himself as promoting a communist version of the Superman. “In labor, in technology,” he wrote, in a passage cited by Watson, “[the new man] found himself to be a god and dictated his will to the world.”

Trotsky thought much the same, opining that socialism would create “a higher social-biologic type.” Lenin always resisted the importation of Nietzsche’s ideas into Bolshevism. But the Soviet leader kept a copy of Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy in his personal library and one of Zarathustra in his Kremlin office, and there is more than a hint of the cult of the will in Lenin’s decree ordering the building of “God-defying towers” throughout the new Soviet state.

It seems that few if any of these towers were constructed, the Soviet authorities devoting their energy instead to incessant anti-religion campaigns. A League of Militant Atheists was set up to spread the message that “religion was scientifically falsifiable”. Religious buildings were seized, looted and given over to other uses, or else razed. Hundreds of thousands of believers perished, but the new humanity that they and their admirers in western countries confidently anticipated has remained elusive. A Soviet census in 1937 showed that “religious belief and activity were still quite pervasive”. Indeed, just a few weeks ago, Vladimir Putin—scion of the KGB, the quintessential Soviet institution that is a product of over 70 years of “scientific atheism”—led the celebrations of Orthodox Christmas.

In many parts of the world at present, there is no sign of religion dying away: quite the reverse. Yet Watson is not mistaken in thinking that throughout much of the 20th century “the death of God” was a cultural fact, and he astutely follows up the various ways in which the Nietzschean imperative—the need to construct a system of values that does not rely on any form of transcendental belief—shaped thinking in many fields. A purely secular ethic had been attempted before (the utilitarian philosophies of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill are obvious examples) but Nietzsche made the task incomparably more difficult by identifying the theistic concepts and values on which these and other secular moralities relied. Ranging widely, Watson tracks the pursuit of a convincing response to Nietzsche in philosophers as various as Henri Bergson, William James and G. E. Moore, painters such as Matisse and Kandinsky, futurist composers and modernist poets (notably Mallarmé and Wallace Stevens), movements such as the Beats and the Sixties counterculture and a host of psychotherapeutic cults.

If Watson shows how Nietzsche’s challenge resonated throughout pretty well every area of cultural life, for Eagleton this focus on culture is a distraction, if not a crass mistake. Discussing Edmund Burke and T. S. Eliot, both of whom viewed religion largely in cultural terms even though they were believers, he asks rhetorically: “Might culture succeed in becoming the sacred discourse of a post-religious age, binding people and intelligentsia in spiritual union? Could it bring the most occult of truths to bear on everyday conduct, in the manner of religious faith?” Historically, the idea that religion is separate from culture is highly anomalous—a peculiarly Christian notion, with no counterpart in pre-Christian antiquity or non-western beliefs. But Eagleton isn’t much interested in other religions, and for him it is clear that the answer to his question must be “No”.

It’s not simply that culture lacks the emotional power of religion: “No symbolic form in history has matched religion’s ability to link the most exalted of truths to the daily existence of countless men and women.” More to the point, religion—particularly Christianity—embodies a sharp critique of culture. A standing protest against the repression that accompanies any social order, the Christian message brings “the grossly inconvenient news that our forms of life must undergo radical dissolution if they are to be reborn as just and compassionate communities”. In making this demand, Eagleton concludes, “Christianity is arguably a more tragic creed than Nietzsche’s own doctrine, precisely because it regards suffering as unacceptable.”

It’s an interesting suggestion, but neither the Christian religion nor Nietzsche’s philosophy can be said to express a tragic sense of life. If Yeshua (the Jewish prophet later known as Jesus) had died on the cross and stayed dead, that would have been a tragedy. In the Christian story, however, he was resurrected and came back into the world. Possibly this is why Dante’s great poem wasn’t called The Divine Tragedy. In the sense in which it was understood by the ancients, tragedy implies necessity and unalterable finality. According to Christianity, on the other hand, there is nothing that cannot be redeemed by divine grace and even death can be annulled.

Nor was Nietzsche, at bottom, a tragic thinker. His early work contained a profound interrogation of liberal rationalism, a modern view of things that contains no tragedies, only unfortunate mistakes and inspirational learning experiences. Against this banal creed, Nietzsche wanted to revive the tragic world-view of the ancient Greeks. But that world-view makes sense only if much that is important in life is fated. As understood in Greek religion and drama, tragedy requires a conflict of values that cannot be revoked by any act of will; in the mythology that Nietzsche concocted in his later writings, however, the godlike Superman, creating and destroying values as he pleases, can dissolve and nullify any tragic conflict.

As Eagleton puts it, “The autonomous, self-determining Superman is yet another piece of counterfeit theology.” Aiming to save the sense of tragedy, Nietzsche ended up producing another anti-tragic faith: a hyperbolic version of humanism.

The anti-tragic character of Christianity poses something of a problem for Eagleton. As he understands it, the Christian message calls for the radical dissolution of established forms of life—a revolutionary demand, but also a tragic one, as the kingdom of God and that of man will always be at odds. The trouble is that the historical Jesus seems not to have believed anything like this. His disdain for order in society rested on his conviction that the world was about to come to an end, not metaphorically, as Augustine would later suggest, but literally. In contrast, revolutionaries must act in the basic belief that history will continue, and when they manage to seize power they display an intense interest in maintaining order. Those who make revolutions have little interest in being figures in a tragic spectacle. Perhaps Eagleton should read a little more Lenin.

Although he fails to come up with anything resembling serious politics, Eagleton produces an account of the continuing power of religion that is rich and compelling. Open this book at random, and you will find on a single page more thought-stirring argument than can be gleaned from a dozen ponderous treatises on philosophy or sociology. Most of the critical turning points in modern thought are examined illuminatingly. Eagleton’s discussion of the religious dimensions of Romanticism is instructive, and his crisp deconstruction of postmodernism is a pleasure to read. He is exceptionally astute in his analysis of “the limits of Enlightenment”—nowadays a heavily mythologised movement, the popular conception of which bears almost no relation to the messy and often unpleasantly illiberal reality.

Evangelical rationalists would do well to study this book, but somehow I doubt that many of them will.

Was Nietzsche right in thinking that God is dead? Is it truly the case that—as the German sociologist Max Weber, who was strongly influenced by Nietzsche, believed—the modern world has lost the capacity for myth and mystery as a result of the rise of capitalism and secularisation? Or is it only the forms of enchantment that have changed? Importantly, it wasn’t only the Christian God that Nietzsche was talking about. He meant any kind of transcendence, in whatever form it might appear. In this sense, Nietzsche was simply wrong. The era of “the death of God” was a search for transcendence outside religion. Myths of world revolution and salvation through science continued the meaning-giving role of transcendental religion, as did Nietzsche’s own myth of the Superman.

Reared on a Christian hope of redemption (he was, after all, the son of a Lutheran minister), Nietzsche was unable, finally, to accept a tragic sense of life of the kind he tried to retrieve in his early work. Yet his critique of liberal rationalism remains as forceful as ever. As he argued with masterful irony, the belief that the world can be made fully intelligible is an article of faith: a metaphysical wager, rather than a premise of rational inquiry. It is a thought our pious unbelievers are unwilling to allow. The pivotal modern critic of religion, Friedrich Nietzsche will continue to be the ghost at the atheist feast.

John Gray is the New Statesman’s lead book reviewer. His latest book is The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths

This piece originally appeared on newstatesman.com.