Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace

by Nikil Saval (Doubleday, 2014)

Five days a week I commute to a skyscraper in the main business district of a large city and sit at a desk within whispering distance of another desk. Whatever the word “work” used to conjure, my version is now quite standard. About 40 million Americans make a living in some sort of cubicle.

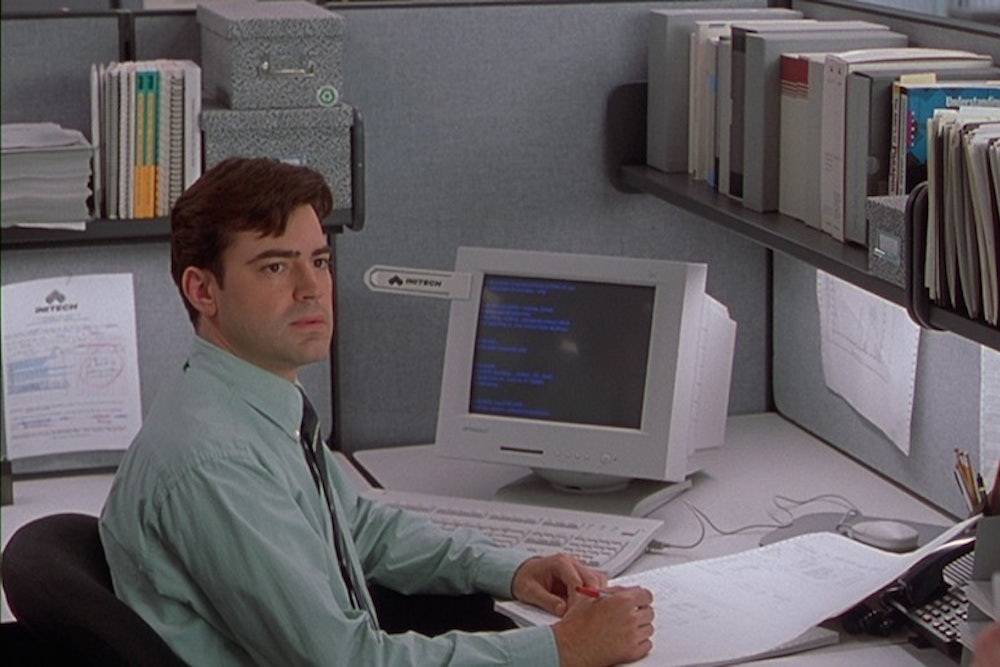

Are we happy about that? The likelihood that we are not is central to Nikil Saval’s impressive debut, Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace![]() . He begins with a description of a viral video purporting to show a spontaneous case of cubicle rage—“purporting” because it may have been a hoax—and lingers on the famous scene from Office Space in which three frustrated employees destroy a fax machine. Having proven his cultural bona fides, Saval explicitly positions Cubed as a pop-modern version of C. Wright Mills’s 1951 White Collar: The American Middle Classes

. He begins with a description of a viral video purporting to show a spontaneous case of cubicle rage—“purporting” because it may have been a hoax—and lingers on the famous scene from Office Space in which three frustrated employees destroy a fax machine. Having proven his cultural bona fides, Saval explicitly positions Cubed as a pop-modern version of C. Wright Mills’s 1951 White Collar: The American Middle Classes![]() , a sociological text that took a dim view of non-manual labor as tedious and isolating.

, a sociological text that took a dim view of non-manual labor as tedious and isolating.

Strictly speaking, Cubed is a history of the office, not office-worker unhappiness. Saval assumes, probably correctly, that offices are ubiquitous to the point of invisibility. Like the young fish in David Foster Wallace’s Kenyon commencement speech—the one who asks: “what the hell is water?”—we are too familiar with our surroundings to bother wondering about them.

Yet as Saval bothers, situating the office in historical perspective, he emphasizes the experience of average workers over those who have ascended to management, and returns again and again to the theme of disgruntlement.

At times he does so out of a descriptive impulse to tell it like it is. On other occasions he plays the role of an activist, prodding us to wake up to our malaise so that we might finally do something about it. He ultimately welcomes the technological and macro-economic changes that could make traditional offices unnecessary because he holds, a little too strongly, to the notion that the white-collar work environment is itself to blame for white-collar dissatisfaction.

The modern office emerged from the “counting houses” of the mid-nineteenth century, and white-collar workers emerged as a class along with it. Back then we called ourselves “clerks” rather than “knowledge workers” and spent our time keeping books for merchants, lawyers, or bankers.

Counting houses were cramped: One typical New York establishment was only 25 square feet yet accommodated four partners and six clerical workers. They were also hopeful. In part because we were so physically close to our employers, we were convinced that we would eventually take their places. For this reason, we thought we were exempt from the Marxist principle that capital and labor are locked in an intractable conflict. Less clinically: We felt justified in rooting for our employers’ success. We saw ourselves “shaking hands” with our bosses instead of shaking fists.

Perhaps fellowship really did exist in the counting-house era. But as time went on, employers took more interest in making us more productive than in bringing us along. Of course we weren’t necessarily cognizant of that fact.

In the early twentieth-century, the Larkin Company, a soap manufacturer turned mail-order operation, hired Frank Lloyd Wright to design a state-of-the-art headquarters in Buffalo, N.Y. Its most distinctive feature was a central court with a metal-and-glass roof that let in natural light for the whole building, and which doubled as an administrative space.

Although the Larkin building was, in a sense, an upgrade over the dingy warrens where we’d toiled before, it was also sinister. In the central court sat rows “of identically attired and coiffured women together in a visual line, guarded at the desk corners by four male executives.” These execs were watching us. The building was “designed for easy supervision and surveillance.”

All that light made us think the company wanted to “take care” of us, as one Larkin secretary put it. Hidden by the glare was the reality that “the numbing work remained the same,” and that managers were constantly spying to make sure the numbing work was completed as efficiently as possible.

Designers have since attempted to make work environments less oppressive, but have generally succeeded only in making things worse. In 1964, the manufacturer Herman Miller unveiled Robert Propst’s Action Office, a “proposition for an altogether new kind of space” that was “about movement” rather than “keeping people in place.” Propst imagined us in “work stations” with two different desks—one for standing, one for sitting—a mobile table for meetings and an acoustically insulated telephone dock (something like a three-sided telephone booth).

When these didn’t sell, Propst tried again with Action Office II. He shrank our stations and surrounded them with three walls made of disposable materials, which we could theoretically arrange to create whatever kind of space we wanted. He gave us tackboards for “individuation.” Sound familiar? He’d invented the cubicle.

Employers loved Propst’s invention, which was cheaper than more traditional furniture. But George Nelson, who had worked with Propst on Action Office I, anticipated their dehumanizing effect. Action Office II “is definitely not a system which produces an environment gratifying for people in general,” he wrote. “It is admirable for planners looking for ways of cramming in a maximum number of bodies, for ‘employees’ (as against individuals), for ‘personnel,’ corporate zombies, the walking dead, the silent majority.”

In the era of the cubicle, the hope of the counting house days felt distant indeed. Not only were we confined in disposable pens, but we were overeducated, and our “expectations were gradually running up against [our] actual possibilities for advancement.” At least we had job security—until of course we didn’t. By the 1980s we were targets for downsizing. “Between 1990 and 1991, 1.1 million office workers would be laid off, exceeding blue-collar layoffs for the first time.” The modern office “asked for dedication and commitment,” but we were offered “none in return.”

Our bosses weren’t blind to our unhappiness and tried, as Propst had tried, to shake things up. There were stunts: Andrew Grove, the Intel C.E.O., played at nurturing an egalitarian culture by sitting at a cubicle. This was “a gesture of pure irony” because “you could hardly be said to occupy a cubicle if you could leave whenever you pleased, probably spent most of your working hours flying around the country in the company jet, and earned $200 million a year.”

And there were earnest attempts at improvement that felt like stunts. In 1993, Jay Chiat of the advertising agency Chiat/Day resolved to “de-territorialize” the office by getting rid of the “walls, desks, and cubicles,” the “desktop computers and the phones.” He thought this would help us focus on work rather than office politics, but it only caused confusion. “People arrived and had no idea where to go, so they left. If they stayed, they found there was nowhere to sit; there were too many people.” We “began playing hooky” and managers couldn’t find us. “No work was getting done.”

In the twenty-first century, tech companies shower us with perks. At Google's Mountain View campus we get free food, a gym, day care, health and dental services, and a resistance pool. Less naïve than in the Larkin days, it’s not lost on us that as companies cater to our needs, they’re trying to do more than make us happy: They’re trying to keep us at work as long as possible, and away from their rivals.

Which isn’t to say that we’ve evolved into a different species since the Larkin building, or even the counting house. Saval emphasizes certain traits that tie together office-workers past and present: Simultaneous frustration with and devotion to our employers; an aptitude for ignoring mistreatment; an inability to impress upon our bosses that they should probably consult us when making design and human resources decisions that affect our daily lives.

Saval is of course aware that he’s telling the story of the office at a moment when it’s in flux. Personal computing and the Internet have made telecommuting feasible and the freelance economy is growing, so that many people who would have labored in a cubicle a generation ago now do their jobs at home or in coffee shops. Careful not to glorify contract labor, Saval concedes that many freelancers have not chosen to leave the permanent workforce: They’ve been pushed out. They don’t have benefits and may struggle for cash.

Still he accepts the precarious life of the freelancer as preferable to that of the old-fashioned cube-dweller. He criticizes “organizations that insist on hierarchy” and praises “the willingness of workers to discard status privileges like desks and offices.”

In predicting that the old career path “from the cubicle to the corner office” is “coming to a close, and that a new sort of work, as yet unformed, is taking its place,” he finally allows himself to sound less like an impartial chronicler than a revolutionary. “It remains for office workers to make this freedom meaningful,” he writes, “to make the ‘autonomy’ promised by the fraying of the labor contract a real one, to make workplaces truly their own.”

Notice the way Saval balances the visual metaphor of the cube-to-corner career path against the abstract notion of new sort of career? In both descriptive and exhortative passages, he muddies the distinction between the misery of work, and the misery of the physical workplace, investing the latter with so much power that it overtakes the former as the true cause of white-collar distress. That’s why Saval finds restorative potential in the office-less future—and why I doubt it will live up to his expectations.

In his introduction, Saval cites a survey by the furniture company Steelcase, which found that 93 percent of people who work in cubicles “would prefer a different workspace.” That’s not terribly surprising but also not terribly enlightening. Would a comparable percentage of people who work in retail, or in factories, or auto dealerships, or industrial farms prefer a different workspace? More pertinent: Would we prefer different work—an entirely different job?

As mentioned, Saval smartly observes that after Larkin moved its employees into its state-of-the-art headquarters, “the numbing work remained the same.” And he suggests that white-collar laborers have often failed to acknowledge the fact of our exploitation. If we leave the cubicle only to bore ourselves at the coffee shop, we will still face exploitation, and dissatisfaction, too.