Economists will tell you that the economic recovery is nearly five years old. But 57 percent of Americans still think we’re in recession and it’s not hard to see why. The unemployment rate is still 6.7 percent. Millions of American workers have dropped out of the labor force, too discouraged to continue looking for work.

So why isn’t the economy recovering more quickly? Technically speaking, the explanation is very simple. And you can see it in a poll that Gallup released on Monday morning.

The survey finds that 62 percent of Americans enjoy saving money over spending it. Just 34 percent prefer spending. This finding holds across every demographic: age, race, income levels, political identification, geographic location, and education level. By nearly a 2-to-1 margin, Americans would rather save money than spend it. And this margin is much higher than it was before the recession.

This may sound like good news—and over the long run, most economists would agree, societies that save more tend to be more productive. But, at times like these, extra saving is almost certainly bad.

When the financial crisis struck, Americans suddenly found themselves out of work and unable to purchase goods and services. In return, they cut back their spending—and one families’ spending is another company’s income. When consumers stopped spending, businesses lost customers and had to cut back as well. That included firing workers, who then cut back their own spending and created a deadly, self-reinforcing cycle (also known as a negative feedback loop). In economics terms, the drop in spending is known as a shortfall in aggregate demand.

Basically: People aren’t buying enough stuff.

This is where countercyclical government policies can make a big difference. Through fiscal or monetary stimulus, the government can close that hole in aggregate demand. They can buy goods and services and spur more investment. This can reverse the negative feedback loop by allowing businesses to expand and hire more workers, who then can buy more stuff and so on.

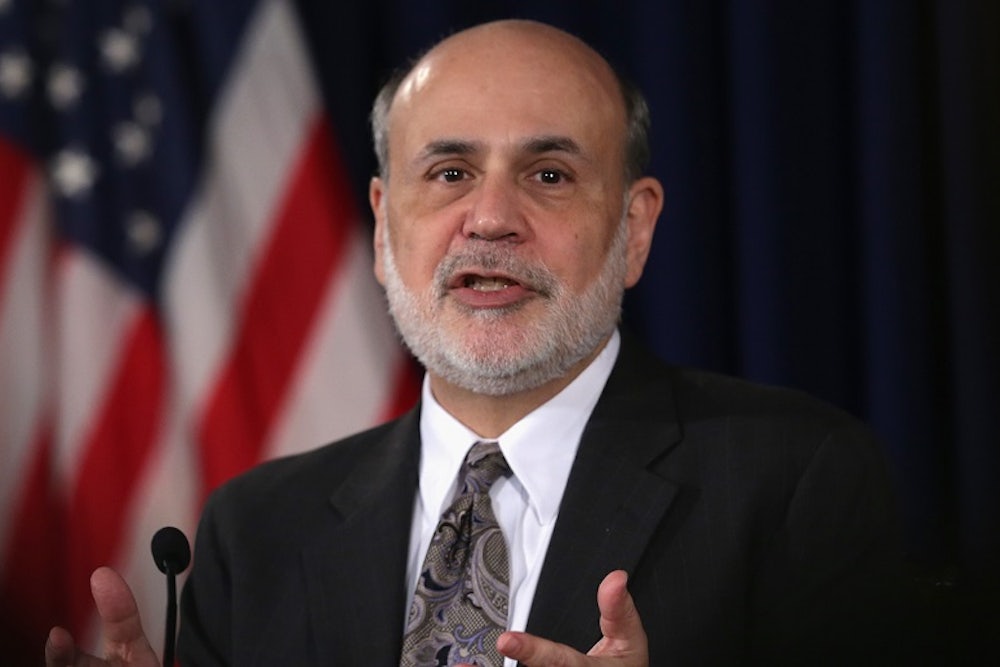

The federal government, through the stimulus, and Federal Reserve, through zero-interest rate policy, quantitative easing and forward guidance, implemented such policies after the financial crisis. But thanks to institutional constraints and legitimate fears about financial stability, the Fed never imposed a higher inflation target or pursued a policy of nominal GDP targeting. Thanks to Republican opposition to fiscal stimulus, the federal government has done more to stand in the way of economic growth with premature austerity than it has to spur a stronger recovery. As a result, fiscal and monetary policy have almost surely succeeded in keeping the downturn from being much worse. But they haven’t allowed the recovery to be as good as it could be.

It’s not too late. Congress could pass more stimulus—more money for infrastructure, for instance. The Federal Reserve could raise its inflation target, although there are serious concerns about financial stability and the distributional consequences of doing so. By creating new businesses and jobs, these policies would make people less anxious about the future—encouraging them to spend so that the graph goes back to looking like normal again.